Hello! A note to new subscribers: this post is an episode in an ongoing (roughly) monthly series about the plants of the Alps, also serving as an exploration of the Plant Tree of Life. If you’re looking for flower-happy mountain adventures, stayed tuned for the next post (probably), in which we will go on a hike in the French Alps and visit an alpine botanical garden.

Welcome back to the Flora alpina, an evolutionary tour of the plants in the Alps.

Previously in the series, we’ve gotten an overview of Alpine plant diversity, stood in awe of the Tree of Life, expanded on the meaning of plant families and Floras, and learned about the evolutionary history of plant sex (trust me, it’s relevant). We’ve explored the lycophytes, the weird ferns, the common ferns, the pine family, and other conifers. After an introduction to the angoisperms, i.e. flowering plants, we met the water lilies and magnoliids.

Today, the first monocots.

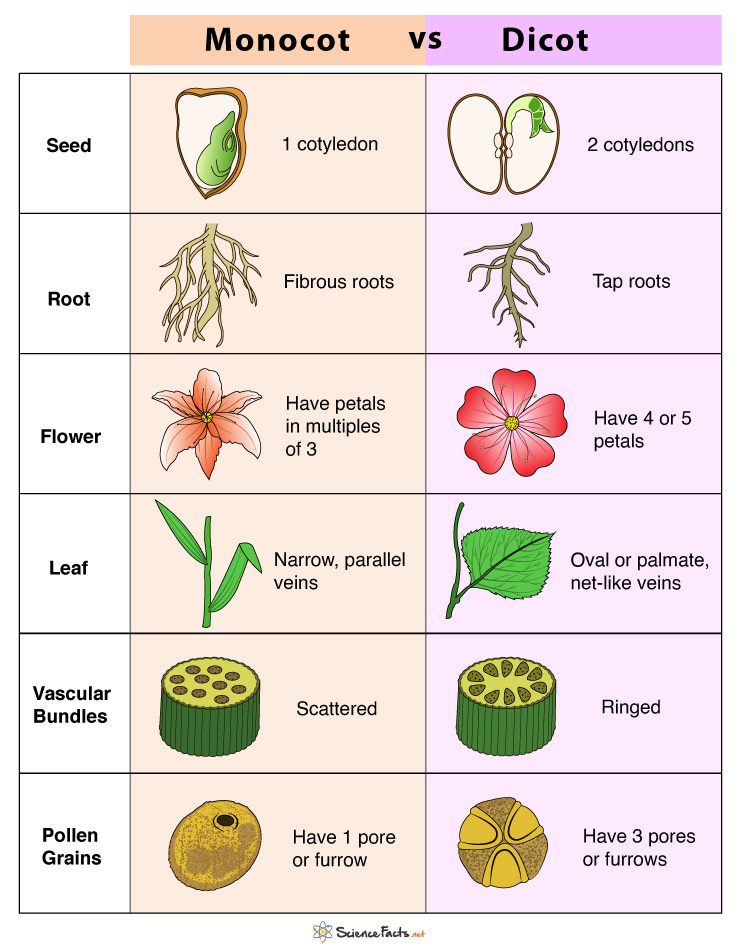

We’re now climbing onto the monocot branch of the Plant Tree of Life. Monocots are a group of plants distinct from the rest of the flowering plants by virtue of having only one seed leaf, or cotyledon, and parallel-veined leaves, among other traits1. As described in my Intro to Angiosperms, the monocots host some of our most important food crops and loveliest flowers, as well as some of the most diverse families in the whole Plant Tree of Life (e.g. grasses and orchids).

Aquatic monocots

The earliest branch of monocots, however, is on the obscure side—to be honest, before starting this project, I didn’t know it existed as such. We’re talking about a monocot order called Alismatales. Although there’s a nice spread of distinct families in this order, from pondweed (Potamogetonaceae) to frogbit (Hydrocharitaceae) to water plantains and arrowheads (Alismataceae) and all four families of seagrass, they share the kind of satisfyingly categorizable trait that can be applied in one broad sweep, probably thanks to a shared aquatic ancestor: the ✨ aquatic monocots. ✨

Aquatic monocots are flowering plants, and while some of them have quite traditional flowers, many of them rely mostly on vegetative reproduction—that is, cloning new plants from the roots or other bits of an existing plant rather than from seed—because water makes pollination tricky (though underwater pollination is possible in some species, either through water currents or aquatic critters). This talent allows some species to colonize waterways rather intensely, making a few of them—like Elodea canadensis—some of the most successful spreaders in the plant world. Seagrass meadows also form some of the most productive ecosystems on earth.

Seagrass doesn’t grow in the Alps, of course, but pondweed does. In the Alps, the aquatic monocots are mostly found in low-elevation ponds. The higher alpine streams are too fast and too cold for gently swaying pond-bottom rooters.

A blended order

There’s more to Alismatales, however: more recently in the taxonomic world, an outer branch has been tacked onto the order, providing the bulk of its species numbers: the very different (yet related), mostly tropical, mostly non-aquatic arum family (Araceae). Arums are those weird plants with sausage-looking centers surrounded by a swath of pointy leaf-collar. AND YET Araceae also includes some rather pondweedy genera, such as duckweed (Lemna), that used to be placed in their own families, until DNA told another story. Phylogeny works in mysterious ways.

Potamogetonaceae (pondweed family)

Global diversity: 5 genera, ~120 species

Alps diversity: 3 genera, 23 species

This family includes a variety of submersible plants aptly named pondweed. Its name (or that of its namesake genus, Potamogeton) charmingly comes from the Greek words for “river” and “neighbor” (recall that hippopotamus means river horse).

Potamogeton (pondweed)

This genus provides the bulk of the pondweed in the Alps with its 21 species. Their water-loving leaves can be stringy like grass, broad and strap-shaped, ruffle-edged, short and stumpy, or what have you. Leaves may vary within the same species or even between identical clones as they respond to factors like water chemistry, depth, sediment conditions, temperature, day length, and season—so identifying species based on leaf shape is iffy (Kaplan 2002). And so although the species tend to have descriptive common names like “broad-leaved pondweed,” “bright-leaved pondweed,” “curly pondweed,” “long-stalked pondweed,” and “flat-stalked pondweed,” this might not tell you much. Their flowers, clustered in a cylindrical stalk, typically lack petals, and the fruits are tiny, round green achenes with pointy ends.

(Reminder: See glossary for bolded terms)

Two other Alpine species from different genera in this family are commonly known as pondweed:

Groenlandia and Zannichellia

Groenlandia densa (opposite-leaved pondweed) is monotypic (the only species in its genus), and has closely nested opposite leaves (in contrast to Potamogeton, which has alternate leaves).

Zannichellia pallustris (horned pondweed), which occurs throughout the world, has stringy, grass-like leaves and tiny unisexual flowers. Its name refers to the shape of its pointy fruits and seeds, which come in clusters.

Hydrocharitaceae (frogbit family)

Global diversity: 14 genera, 135 species

Alps diversity: 3 native genera, 4 species; 3 introduced genera, 5 species

The frogbit family has a range of freshwater aquatics, and is also one of the handful of families of seagrass.

Najas (naiad)

There are two globally widespread species of naiad in the Alps, N. marina (holly-leaved naiad) and N. minor, and one introduced North American species, N. gracillima. They have clumps of fine leaves, from thread-like to flat and serrated in holly-leaved naiad. Flowers are tiny and petal-free; the fruit is a tiny brown achene.

Hydrocharis (frogbit) and Vallisneria (tapegrass)

Hydrocharis morsus-ranae, frogbit, has tidy, unisexual, three-petaled white flowers and round floating leaves like miniature lily pads. It can create dense layers on the surface of the water.

Vallisneria spiralis, tapegrass, has long underwater blades (though it’s not a true grass).

Elodea

Elodea, an introduced genus, is worth mentioning because it’s everywhere, especially Elodea canadensis, Canadian waterweed. It’s very good at cloning, and it’s thicc, so it’s considered an invasive species in many places outside North America, with warnings accompanying its use as an ornamental pond/aquarium plant. The leaves are completely submerged, but the delicate flowers with three pale, waxy petals and fuzzy pink stigmas float on the water.

Alismataceae (water plantain family)

Global diversity: 17 genera, ~120 species

Alps diversity: 3 genera, 6 species

This family features plants that grow in or near the water without being fully submerged, so they tend to have reasonably showy three-petaled flowers.

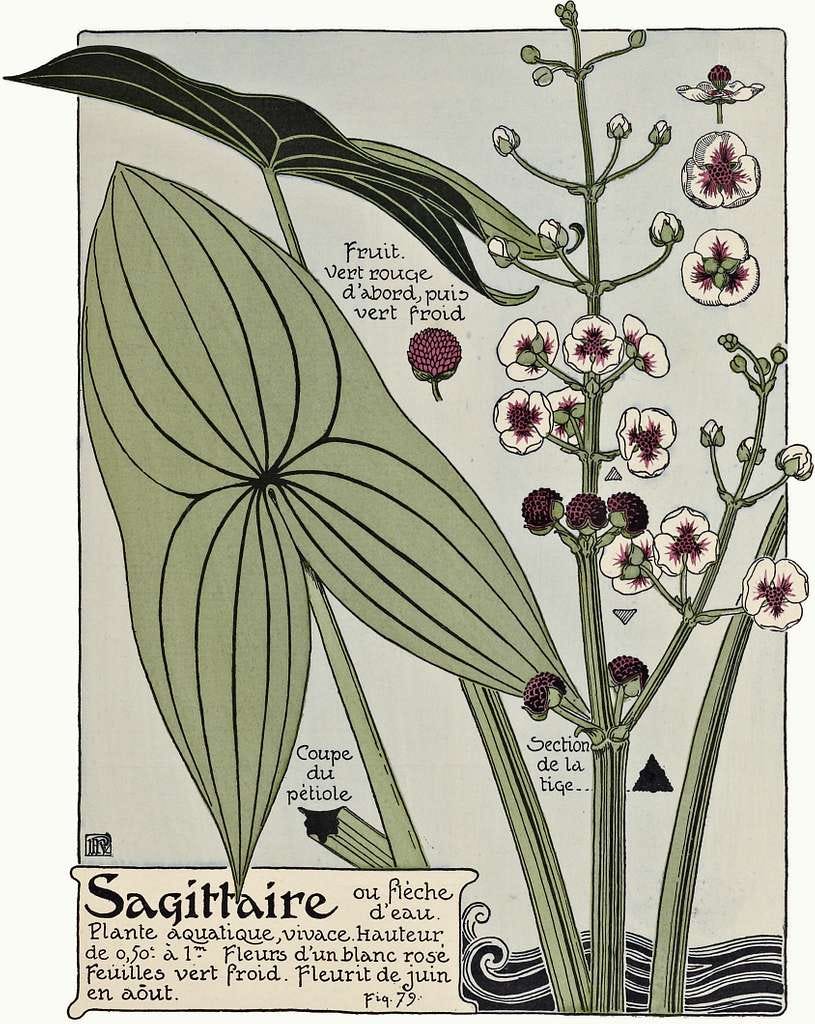

Sagittaria (arrowhead)

Sagittaria sagittifolia (arrowhead) is native to Eurasia, with striking three-pointed leaves, attractive white-petaled, purple-stamened flowers, and edible tubers. Its introduced North American cousin, S. latifolia, is known as wapato, duck-potato (!), and katniss, among other excellent names. Its leaves are broader than European arrowhead. The other N. American introduction, S. platyphylla, is less arrow-shaped and more traditionally leaf-shaped.

Alisma and Baldellia (water plantains)

Two widespread Alisma species (A. plantago-aquatica and A. lanceolatum) and one western European species, Baldellia ranunculoides, are all called water plantains (because their leaves look similar to the OG terrestrial plantains, Plantago). Alisma is also called mad-dog weed due to being a purported cure for rabies.

Water-plantain flowers have the characteristic three white or pinkish petals, but Alisma flowers, though borne in many-branched clusters, are less conspicuous than Baledellia ranunculoides. Their leaves are broad-bladed. B. ranunculoides produces spiky ball-shaped fruit, and Alisma produces a squat disk ringed with seeds.

Wikipedia bonus fact: “The nineteenth century British art and social critic John Ruskin believed that the particular curve of the leaf-ribs of Alisma represented a model of 'divine proportion' and helped shape his theory of Gothic architecture.”

Butomaceae

Butomus umbellatus – flowering rush

Monotypic family

Though not a true rush, this species has long, ribbon-y leaves. The flowers are pinkish with 3 petals alternating with petal-like sepals, borne in conspicuous clusters at the end of the tall stem. It has dry, multi-seeded fruits, but mostly reproduces vegetatively from rhizomes that generate new plants from the root.

Scheuchzeriaceae

Scheuchzeria palustris – rannoch rush

Monotypic family

This is also not a rush, but also has narrow ribbony leaves. It has tiny greenish flowers with 6 tepals that produce clusters of tear-drop shaped fruits. It likes Sphagnum peat bogs (palustris refers to swamp).

Juncaginaceae

Global diversity: 3 genera, 34 species

Alps diversity: single species

Triglochin palustris - marsh arrowgrass

Found in damp meadows/marshes, not fully aquatic. Grass-like blades, tall spikes lined with 6-tepaled flowers topped with purplish-white tufts, forming globular fruits close to the stem.

Araceae (Arum family)

Global diversity: 114 genera, 3750 species (especially in the tropics)

Alps diversity: 4 genera (1 exotic), 10 species

When Araceae was lumped into the Alismatales order, it greatly expanded the order’s diversity. There are only a few representatives in the Alps, however. A few of those are the family’s namesake arums and vaguely similar things, and the other half are species of duckweed.

Wikipedia bonus fact: “An interesting peculiarity is that this family includes the largest unbranched inflorescence, that of the titan arum,2 often erroneously called the "largest flower", and the smallest flowering plant and smallest fruit, in the duckweed, Wolffia.”

Arum

Arums, also known imaginatively (read: innuendo) as jack-in-the-pulpit, lords-and-ladies, and cuckoopint (yes even this is innuendo) and a litany of other entertaining and suggestive names3, are distinctive for their rod-shaped inflorescence, the “spadix”, which is hooded by a showy bract called the “spathe.” Variations on this form are characteristic of most of the family, though not all of it, as we will see.

The flowers are clustered at the base of the spadix, sheathed in the spathe in a vase-like bulge. The spadix is able to generate heat4, wafting out its fecal aromas to tempt dung- and decay-loving insects down to the flowers, where a ring of hairs traps them into doing the pollinating.5 These shenanigans result in bright red, highly astringent and toxic berries.

Arums’ big, broad, arrow-shaped leaves are not particularly monocot-esque, with veins that look more branchy than parallel. Their tubers are high in starch, making them useful in the past for starching (humans’) collars and other laundry.

The three woodland species found in the Alps at low elevations are all fairly similar, but Arum maculatum is the most widespread.

Calla palustris – bog arum

Bog arum, Calla palustris, is the only species in its genus—what we call calla lilies used to be a part of this genus, but were moved to Zantedeschia while holding on to the common name. Bog arum resemble our other arums but the flowers are on the tip of the spadix instead of the base, and its leaves are often rounder and fuller than its cream-colored spathe. And it does indeed grow in bogs.

Dracunculus vulgaris - dragon lily

The dragon lily, introduced from the Balkans and only occurring in a few places in the Alps, nevertheless gets a mention because it’s so cool looking: it has a fabulous maroon ruffle sleeve (spathe) for a tongue (spadix) so purple it’s almost black.

Lemna + Spirodela – duckweed

The duckweed genera are about as different from the arums as you can get, and yet their genes place them in the same family. There are four species of Lemna and one of Spirodela in the Alps, and all consist of tiny free-floating round leaves that clone themselves with abandon into floating mats on the water. They technically have flowers, but they’re rarely seen—in fact, they’re microscopic. They also have little roots, but they just dangle in the water.

In the wider world, duckweed is used for bioremediation (in other words they suck up all the heavy metals, so don’t eat them probably), as a model organism for biological research, as a biofuel, and as livestock feed.

Up next in Flora Alpina

Liliaceae, the lily family: Lilies, tulips, fritillaries; Asparagaceae, the asparagus family: hyacinth, solomon’s-seal, bluebells, and more; and a few other lily-like families.

Glossary

Taxonomy

Genus (plural genera), family, order, class: In taxonomy, progressively higher organizational levels above species

-aceae (ay-see-ee): Suffix of a plant family

Gymnosperms: seed plants without fruits, only “naked seeds” growing on bracts

Angiosperms: flowering plants; seed plants which enclose their seeds in fruits, which form from flowers

Basal angiosperms: branches of the angiosperm tree of life that diverged early from the rest, near the base of the tree

Monocots: One of the large branches of the angiosperm tree of life; has seeds with a single seed leaf or cotyldeon, parallel leaf veins, and three-petaled flowers. Includes grasses, orchids, lilies, and more.

Eudicots: The other main branch of the angiosperm tree of life, plants with two seed-leaves, branching leaf-veins, and 4- or 5-petaled flowers. Includes sunflowers, roses, maple trees, and more.

Monotypic: A taxonomic group (like a genus or family) with only one species

Flower anatomy

Whorl: one of the four units of a flower (sepals, petals, stamens, carpels)

Sepals: outer whorl of flower which can be leaf-like or petal-like; collectively called the calyx

Petals: second whorl of flower that can be modified to aid pollination; collectively called the corolla

Tepals: in some flowers, petals and sepals that are undifferentiated

Perianth: sepals and petals (or tepals) considered collectively

Pollen: male gametophyte (see glossary for ferns) containing male reproductive cells

Stamen: male reproductive organ in flowers with anthers that produce pollen, held up by filaments

Androecium: all the male organs of a flower together

Ovule: female reproductive structure that becomes a seed when fertilized (female gametophyte)

Carpel: female reproductive organ in flowers, consisting of stigma that recieves pollen and a style that leads to the ovary

Ovary: the base of the carpel, containing ovules, which becomes the fruit

Pistil: one or more carpels

Gyonecium: the combined female reproductive parts of a flower (multiple carpels or pistils fused together)

Fruit classification

Achene: a type of simple, dry fruit consisting of a single seed

Capsule: a type of dry fruit with several carpels that splits open to release seeds

Berry: a type of fleshy fruit formed from one flower with a single ovary

Drupe: a type of fleshy fruit with a pit

Other anatomy and life history

Cotyledon (seed leaf): The first leaf (or leaves) that forms within the seed and emerges when a plant germinates; typically doesn’t resemble mature leaves.

Rhizome: an underground shoot that can establish new vegetative growth

Bract: A modified leaf that surrounds a flower

Habit: the overall form a plant takes, such as tree, shrub, or herbaceous plant

Herbaceous: lacking wood

Vegetative reproduction: when new plants are generated by cloning, e.g. growing from a rhizome, rather than from seed

Annual: plant life cycle finishes within one year

Perennial: plant persists from year to year

Some monocot vs eudicot facts (dicot is an old-fashioned term)

The titan arum is also known as corpse flower because of the rotting stench it gives off to attract flies.

Wikipedia lists Adam and Eve, adder's meat, adder's root, arum, wild arum, arum lily, bobbins, cows and bulls, cuckoo pint , cuckoo-plant, devils and angels, friar's cowl, jack in the pulpit, lamb-in-a-pulpit, lords-and-ladies, naked boys, snakeshead, starch-root, and wake-robin. Jeremy Bartlett adds: “Red-hot-poker, Willy lily, Snake’s meat, Starchwort, Cheese and toast, Sonsie-give-us-your-hand, Tender ear…. But even Cuckoo Pint is rather rude, because “pint” doesn’t refer to an imperial measure of volume, but should be pronounced to rhyme with “mint”, for it is an abbreviation of “pintle”, meaning penis.”

The word for this is thermogenesis, with starch as the fuel; Jeremy Bartlett: “The temperature of a mature Arum maculatum spadix can range from 25 to 35°Celsius and is often up to 15°C warmer than its surroundings. Starch is metabolised to do this; it is stored in the plant’s root tuber. The heat is mostly generated via a separate mitochondrial respiratory pathway by a cyanide-resistant alternative oxidase (AOX), described by Wagner, Krab, Wagner and Moore in a 2008 paper.”

Sometimes over several days to allow the male flowers to mature in sequence and prevent self-pollination.

https://substack.com/@egretlane/note/p-166722903?r=5ezmlv&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action