Welcome back to the Flora alpina, an evolutionary tour of the plants in the Alps.

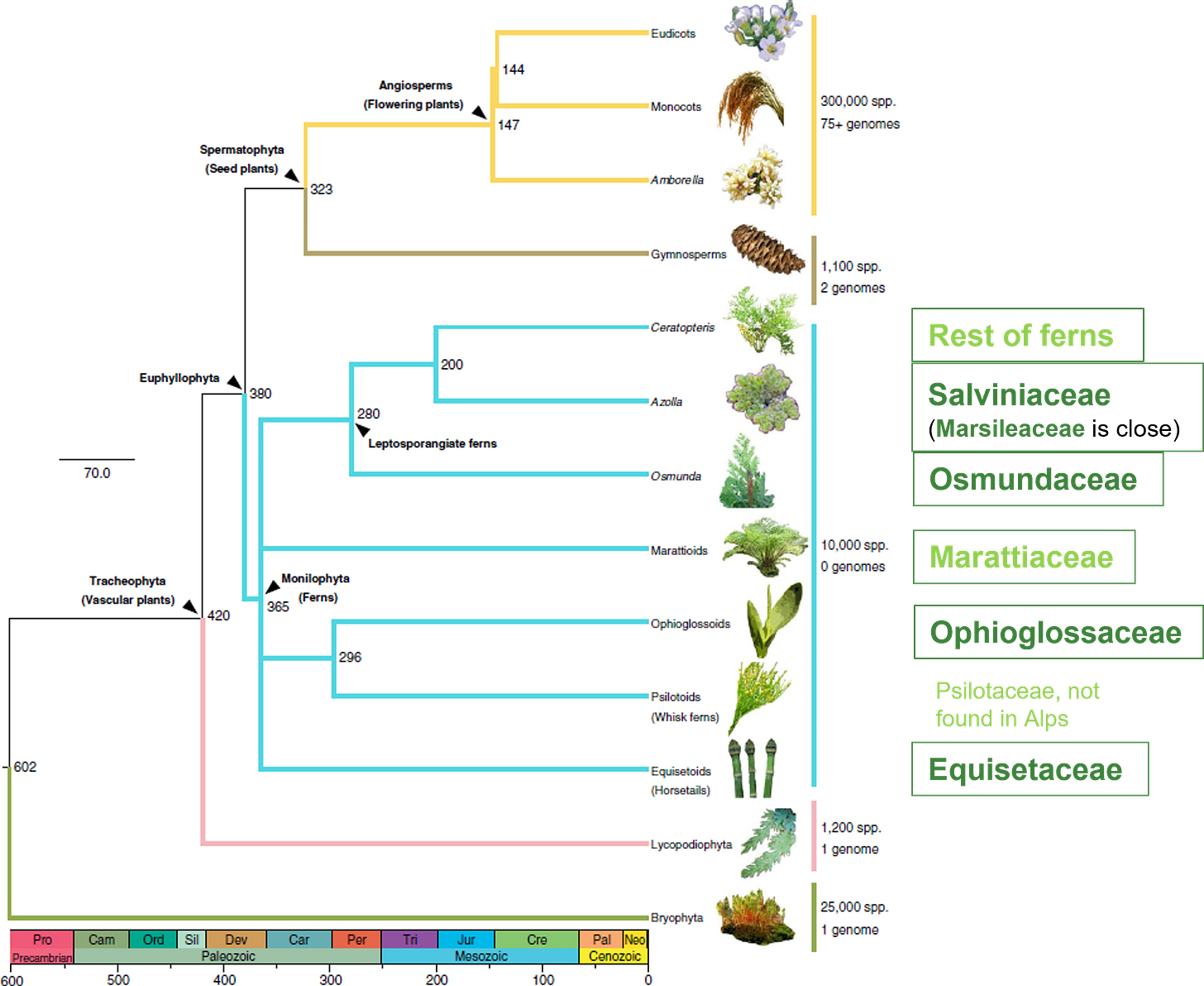

Previously in the series, we’ve gotten an overview of Alpine plant diversity, stood in awe of the Tree of Life, expanded on the meaning of plant families and Floras, and learned about the evolutionary history of plant sex (trust me, it’s relevant).

The last installment featured the lycophytes.

Today: weird ferns.

What is a fern? You probably picture frilly-edged fronds cross-hatching the forest floor or a brackeny hillside. The vast majority of the world’s ~10,000 living species of ferns do fit something like this description. However, the name “fern” casts a much wider net. The fern class, Polypodiopsida (also known as Monilophyta1), encompasses a motley kinship of plants with spores and multi-veined leaves (called megaphylls, an upgrade from lycophytes’ simpler microphylls). Under this big evolutionary tent, ferns can resemble bottlebrushes, spades, fans, whisks, grape bunches, Velcro pads, and even four-leaf clovers.

As with the lycophytes, many of these weird fern groups stand out because they’re isolated remnants of ancient, once more diverse and populous lineages. In other words, they are relict lineages. Also like the lycophytes, some of their ancestors were Carboniferous big shots 350 million years ago.

Today, they’re just weird.

In the Alps, only a few weird fern groups are represented, and none are unique to the region. However, the Alpine sampling gives us a good idea of the most globally widespread ones.

“Weird fern” is not a scientific designation, by the way. If we were to group together the handful of families I’ve gathered below and call it an evolutionary lineage, it would be “paraphyletic”—basically, cherry-picking among related groups. (In this case, leaving out the most recognizable, core group of modern ferns, which we’ll cover next time.)

Equisetaceae (Horsetails)

Worldwide: 1 genus (Equisetum), 20 species

Alps: 9 species

The horsetails (Equisetum), a ubiquitous though not a species-rich group, are arguably the most iconic weird ferns. You may know them as snakegrass, puzzlegrass, scouring-rush or some other evocative name. They pop up along streams and in marshes with elegantly segmented stems and bristlebrush leaves collaring each node, strikingly unlike any other plant around.

Fertile horsetails are tipped with a strobilus: a cone-like cluster of sporangia, which make spores. The way sporangia are arranged is one of the big things setting horsetails apart from other weird ferns (and normal ferns), which don’t have strobili. (Other ferns instead have clusters of sporangia called sori found on variously shaped fertile leaves.)

Equisetum stems are hollow—did you ever walk along a stream as a kid, break off a snakegrass segment and try to play it like a kazoo?

Or, did you ponder the ineffable sense of otherworldliness provoked by such an Art Deco alien, like I did?

Or notice the pattern of nodes stacking progressively closer together up the stem and come up with the concept of logarithms, like John Napier?2

Around half of all horsetail species are found in the Alps. I happened on one alongside a mountain pond; I don’t think most of them would be hard to find. Equisetum is a widespread genus.

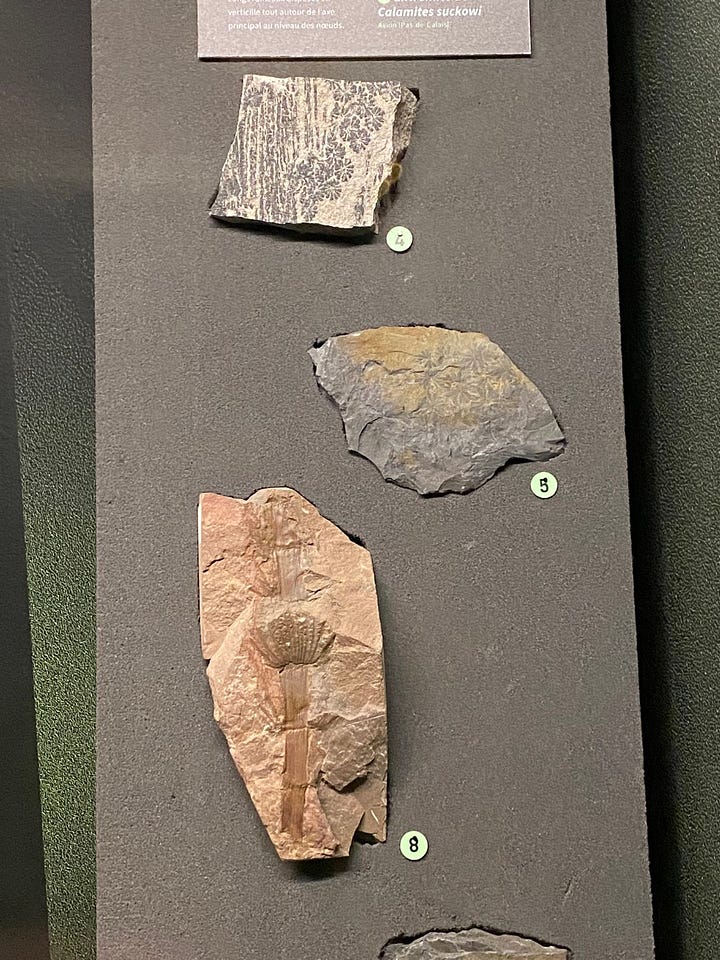

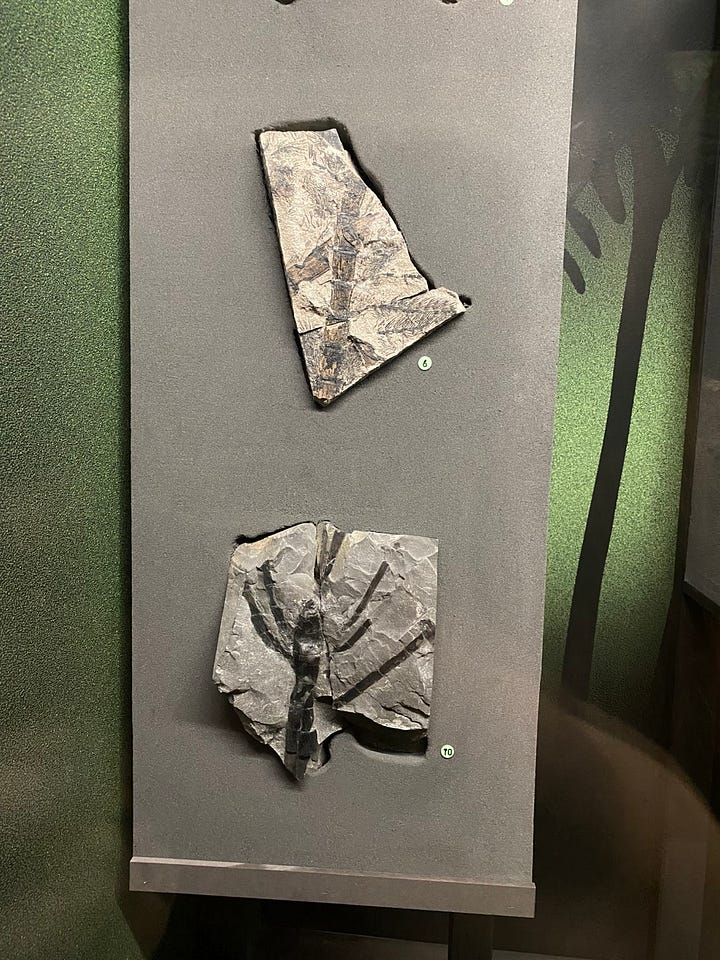

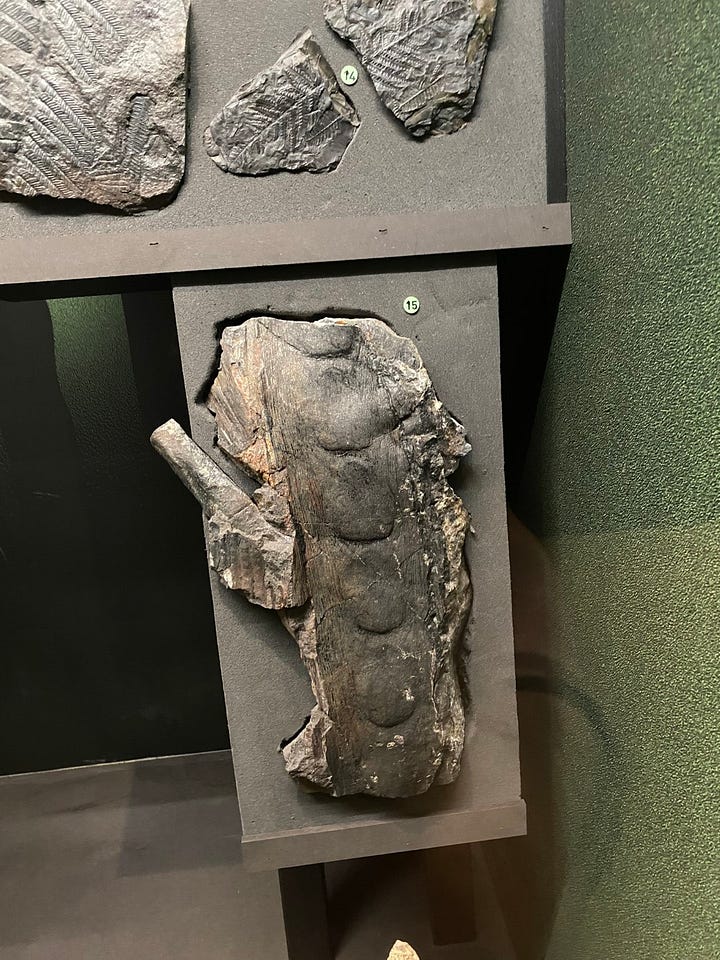

Giant arborescent horsetails once grew alongside the lycophyte scale trees in the Carboniferous jungles, leaving fossils of robust segmented trunks from extinct Equistales genera Calamites and Asterophylites and frilly leaves from Annularia. Today’s horsetails might be smaller, but the family resemblance is strong.

Ophioglossaceae (Adder’s tongue family)

Worldwide: ~13 genera, ~80 species (depends on which taxonomist you ask)

Alps: 7 species

Some ophioglossid ferns are also called grape ferns because their sporangia are stored in globular clusters hanging along a central stem. Surrounding the fertile stems might be a single spade-shaped frond, as in the adder’s tongue ferns (e.g. Ophoglossium vulgatum), or pinnate, crescent-shaped fans, as in the moonworts. The first time I spotted the most cosmopolitan moonwort, Botrychium lunaria, unfurling in a mountain meadow in the Alps, I felt like I had caught some kind of Pokemon. I was also surprised (and charmed) by how diminutive it was.

Ophioglossid spores must sift into the soil to germinate into even tinier gametophytes, some of which depend entirely on underground fungi. Their sporophyte offspring, the plants that leaf above ground and make spores, also rely heavily on symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi.

Osmundaceae (Royal fern family)

Worldwide: 6 genera, ~25 species

Alps: 1 species (Osmunda regalis)

The royal fern (Osmunda regalis) looks more like a classic fern with rows of long, pinnate leaflets along its fronds. What’s weird about it is that the sporangia are clustered in dense, showy fertile leaves that almost resemble flower stalks. The sporophyte grows from sturdy rhizomes, exploratory underground stems, and can get quite big for a European fern.

As with other weird ferns, regardless of appearance, the family is simply evolutionarily alone, having split from other ferns sometime in the Carboniferous or Permian Era, leaving a trail of fossils and this lonely living lineage.

Marsileaceae (Water clover family)

Worldwide: 3 genera, ~70 species

Alps: 1 species (Marsilea quadrifolia)

This elegant aquatic family graces us with ferns resembling four-leaf clovers that float on pond surfaces. The resemblance is superficial, meaning it’s not due to shared evolution; it’s just a coincidence. But they look lucky all the same!

Marsilea quadrifolia is common in the northern hemisphere (and popular with aquarium suppliers) but is mostly limited to the central Alps. It’s also known as pepperwort, due to another weird trait of the family: the sporocarp, or fertile leaves that have evolved into pod-like pockets to hold the sporangia, and which look a bit like peppercorns. (I think they look more like beans.)

Salviniaceae (Floating fern family)

Worldwide: 2 genera, ~20 species

Alps: 1 species (Salvinia natans)

Another aquatic family found in the central Alps, Salviniaceae shares some qualities with Marsileaceae (being members of the same order, Salviniales), including a trait unusual in ferns but the norm in seed plants, which is heterospory: two sizes of spore (big and small). Both are produced in the same clusters of sporangia within sporocarps, instead of separately, which is also weird.

Salvinia natans is a prolific freshwater cover plant with weird bristles on its leaves for wicking away excessive water. Submerged under each pair of leaf-pads is a third stabilizing leaf with root-like divisions and hairs.

(Another name I spotted was “water spangles,” which tickles my poet heart.)

Honorable Mentions

Marattiales (tropical tree ferns): The extant family Marratiaceae is exclusively tropical and so doesn’t occur in the Alps, but ancestral tree fern fossils in the order Marratiales have been uncovered in the Alps.

The living species of Marattiales can still take arborescent forms. Aroborescence is one of the defining features of another order of ferns, Cyatheales, which is well represented in tropical and temperate rainforests. Walking under 10-meter-tall tree fern canopies in New Zealand is the closest I’ve come to a Carboniferous time machine.

One last shoutout to a weird fern group found in rainforests: Hymenophyllaceae, the filmy ferns, including the ethereal kidney fern I spotted growing on tree trunks in the New Zealand rainforest.

Phylogeny

Up next in Flora Alpina

Polypodiaceae, the common (less weird) ferns

For those interested in a more comprehensive experience, I’d also like to make a page/guide dedicated to explaining how phylogenies work and giving a better overview of the Plant Tree of Life. I feel like I’ve just been dropping bits of phylogeny lore here and there without properly contextualizing it! Once I get around to it, I’ll probably link the page in the next Flora Alpina post rather than emailing it separately. Feel free to just enjoy the plants without thinking too hard about the logic, if you prefer!

Glossary

Genus (plural genera), family, order, class: In taxonomy, progressively higher organizational levels above species

-aceae (ay-see-ee): Suffix of a plant family

-ales (ay-lees): Suffix of a plant order

Phylogeny: a visual representation of branching evolutionary relationships in the tree of life, similar to a family tree

Monophyletic: A tidy subgroup of a phylogeny that includes all the descendants of a particular node/branching point

Paraphyletic, polyphyletic: Untidy subgroups of a phylogeny that only include some of the descendants of a particular node (polyphyletic is even messier than paraphyletic, taking branches from disparate parts of a tree).

Relict lineage: A group of living organisms remaining from a once much more diverse extinct group

Vascular plants: Plants with veins, including lycophytes, ferns, gymnosperms (e.g. conifers), and angiosperms (flowering plants)

Spore: A reproductive cell produced by asexual splitting (lots more on that here)

Strobilus (plural strobili): A cluster of fertile leaves (sporophylls) where spores are found

Sporangia: Sacs where spores form

Sorus (plural sori): Clusters of sporangia in ferns

Sporophyll: Fertile leaf where sporangia are clustered

Sporocarp: A modified pouch-like sporophyll found in the Salviniales order of ferns

Gametophyte: One of the two generational phases of plants, the organism that produces gametes for sexual reproduction, tiny (made up of only a few cells) in ferns (lots more on alternation of generations here)

Sporophyte: The generation that produces spores, larger and more vegetative than the gametophyte in ferns

Heterospory: When a sporophyte produces two sizes of specialized spores, uncommon in ferns (but the norm for seed plants)

Microphylls: Small, simple versions of vascular leaves with only one vein, found in lycophytes

Megaphylls: More complex leaves with branching veins, found in vascular plants other than lycophytes

Arborescent: Growing in the form of a tree

Pinnate: A compound leaf shape with pairs of smaller leaflets along the stem

Cosmopolitan: A species that is found across most of the earth

Mycorrhizal: Refers to the symbiotic relationship between fungi and the roots of plants, with fungus typically living within or around the roots and exchanging nutrients and chemicals

Rhizome: Underground stem that runs horizontally and grows both roots and new shoots as it extends

The nomenclature of ferns and related groups has undergone its own evolution. “Pteridophyta” once referred to all spore-producing vascular plants, including lycophytes—also called “fern allies”—but because of the way these branches of the plant Tree of Life are nested, grouping lycophytes with ferns creates a paraphyletic group (see glossary) so this fell out of fashion (though the term pteridophyte is still informally in use). Horsetails may or may not be included in “ferns”, but they do form a monophyletic group with the other ferns. This monophyletic group was Monilophyta, and later Polypodiophyta, and after another reorganization of the family tree, was designated as an official class (instead of just a general, unranked group) with the name Polypodiopsida (by far the most fun to say). Monilophyte is also still in use as an informal term for ferns.

John Napier was a 16th century polymath. The only evidence I’ve found for the logarithm story so far is a New Yorker article by Oliver Sacks, so it’s probably an urban legend.

Such an excellent and informative article, Anne. I love to read and learn about ferns. Thank you for writing and sharing.

Oh good!