Welcome back to the Flora alpina, an evolutionary tour of the plants in the Alps.

Previously in the series, we’ve gotten an overview of Alpine plant diversity, stood in awe of the Tree of Life, expanded on the meaning of plant families and Floras, and learned about the evolutionary history of plant sex (trust me, it’s relevant). So far we’ve explored the lycophytes, the weird ferns, and the common ferns.

The invention of seeds

Around the time that lycophytes and ferns ruled the Carboniferous coal-swamps, another branch of the Plant Tree of Life was tinkering with its spore-bearing functions. Their evolutionary experiment—in which spores, instead of flying off in the wind, were encapsulated on fertile leaves, where their tiny offspring would make their own embryos without ever leaving their casing—resulted in seeds.

(For a whole post expanding on that brief introduction, read here about seeds and spores.)

Seeds were a very good idea. So much so that the rest of the plant diversity on this tour of the Alpine Flora are seed plants: Spermatophyta.

The gymnosperms: Before fruit

The first major seed-bearing plant group to take off during the Carboniferous (and also make it all the way to the Holocene) were the gymnosperms. These are the plants who bear their seeds on bracts, specialized leaves that are usually clustered in cones.

Gymno = naked; sperm = seed. “Naked” because gymnosperms evolved before fruits were invented (by angiosperms), so their ovules (which become seeds once they’re successfully fertilized by pollen) sit on their bracts in their birthday suits.1

Like the ferns, the gymnosperms represent a wide range of evolutionary history. They include the familiar conifers, trees such as pine, spruce, fir, juniper, yew, and redwoods (as well as podocarps in the southern hemisphere)—but also totally weird stuff like ginkgo trees, cycads, Ephedra, and Welwitschia.

For such a disparate group with such a dominant presence in temperate forests, it’s a shockingly species-poor one, with only around 1,000 species globally. Compare this to the ferns, which have ~10,000 species, and flowering plants, whose count rockets to ~300,000.

In the Alps, the number of gymnosperms comes down to just 15 native species and ~5 exotic species. And yet several of these trees—in some cases the sole species representing their genus in the Alps—define whole vegetation belts. (I touched on vegetation belts in this intro post, but we’ll revisit them in more detail below, after we get to know the Pinaceae family.)

Because of the outsized importance of this handful of species, we’ll get down to the species level in this part of the tour. Part I will cover the most diverse family, Pinaceae, and the rest will come in Part II.

Pinaceae

If you know the name of any needle-leafed, evergreen, coniferous tree, it’s probably pine. But this name is quite a broad brush to paint with. Not only are there multiple species of pine—around 190 species globally in the genus Pinus—but it’s also not the only kind of conifer you’ll encounter in a forest, nor in Pinaceae, the wider family named for pine. In the Alps, there’s also fir (genus Abies), spruce (genus Picea), and larch (Larix). You might also see the exotic species Atlas cedar (Cedrus atlantica, from North Africa) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii, from North America).

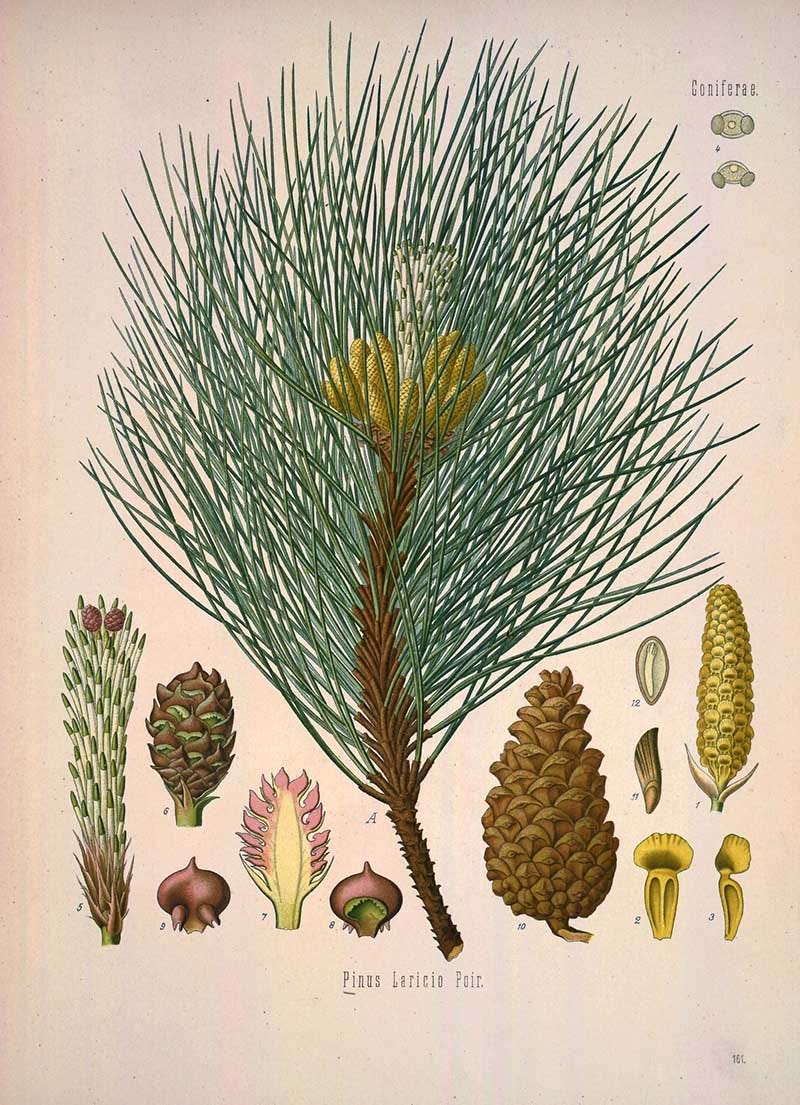

Although these needle-leaf trees look similar at first glance, they each have their own style. The most striking diagnostic features are the needles and the female cones—i.e. the cones with seeds. For example, pines (Pinus) have bundled needles and rigid, woody cones; spruces (Picea) have stiff, spiky pegs for needles, and bendy cones that hang down on the branhces; firs (Abies) have supple, flattened needles and tightly imbricated cones that sit upward on the branches; and larches (Larix) have delicate tufts of deciduous needles and small round cones. (All these trees also have male cones—the small, soft yellowish ones bearing pollen—but they’re less distinctive.)

Pinaceae species are the stars of high-elevation forests in the Alps, and their habitat preferences are a major ingredient of mountain vegetation belts2:

At lower, warmer elevations, the foothills are dominated not by gymnosperms but by broadleaf trees like European beech (Fagus sylvatica). Because conifers are hardier to cold than broadleaf trees, beech forests begin giving way to mixed forests of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), silver fir (Abies alba), and Norway spruce (Picea abies) as altitude increases into the montane zone. In the subalpine zone, broadleafs disappear entirely, spruce becomes more dominant, and fir is replaced by larch (Larix decidua), stone pine (Pinus cembra), and mountain pine (Pinus mugo). Which pines you see also depends on where in the Alps you are: in the east, black pine (Pinus nigra) is more common, and in the southwest, we see Mediterranean species that thrive in warmer, drier conditions such as Pinus halepensis (Aleppo pine), and Pinus pinaster (maritime pine).

Above treeline, only dwarf conifer trees and shrubby species like juniper (Juniperus, from the Cupressaceae family) survive the winter.

Abies alba ~ European silver fir

Diversity: The only Abies species in the Alps; ~50 species globally

Needles: Flattened, springy, single on the stem

Cones: Oblong with tightly layered bracts

Mature cones perch upright on the branches

Bracts/scales come loose when ripe to distribute seeds

Preferred habitat: Montane and subalpine

Distribution: European mountains

French common name: Sapin

Like other firs, Abies alba tends to grow tall, narrow, and conical. Along with spruce, it blankets much of Europe and is widely grown for timber.

Picea abies ~ Norway spruce

Diversity: The only Picea in the Alps; ~40 species globally

Needles: Peg-like and sharp, single

Cones: Oblong and flexible with triangular, scale-like bracts

Mature cones hang down on the branches

Preferred habitat: Montane and subalpine

Distribution: Northern and central Europe, mountains and boreal zones

French common name: L’épicéa commun

Norway spruce is a large, full tree with dense branches in a classic Christmas tree shape (and indeed is commonly planted in Christmas tree farms, as well as ornamentally and for timber). It has the largest cones of any spruce. As well as tolerating cold at higher elevations than silver fir, its range extends farther north, into Sibera.

Larix decidua ~ European larch

Diversity: The only Larix species in the Alps; ~10 species globally

Needles: a deciduous conifer, with delicate tufts of needles that sprout tender green in spring and turn copper and shed every autumn

Cones: Egg-shaped, small and dainty

Preferred habitat: Subalpine, especially disturbed areas

Distribution: Alps and Carpathian mountains

French common name: Mélèze commun

Larches are special in being deciduous3; most needle-leaf trees are evergreen, investing in the longevity of their leaves and replacing them gradually over time rather than dropping them seasonally to conserve energy in the winter. Both strategies apparently have their benefits! Larches also grow aggressively and are good at colonizing habitats that have been scrambled by rockslides, fires, or human development.4

When I rode the cable car to the glaciers of La Meije in this post, larches dominated the forests below us. In the village at the bottom, I tasted larch-flavored ice cream.

Pinus

Diversity: 6 species in the Alps; ~190 species globally

Needles: long and thin, coming in countable bundles (fascicles) of at least two, slotting nicely together, with the base wrapped in a sheath

Cones: rigid and woody, distinct bracts tipped by prickle or point

Preffered habitat and distribution: Depends on species

French common name: Pin5

Pinus sylvestris (Scot’s pine)

Pinus sylvestris is widespread in montane (mid-elevation) forests across northern Europe, privileging rocky and less fertile soils where it can outcompete vigorous species like spruce. Its needles come in pairs, its cones are small and tidy, and its bark is scaly and reddish.

Pinus cembra (stone pine)

The stone pine, or Swiss stone pine, is only found in the Alps and scattered parts of the Carpathian mountains in Eastern Europe. It’s slow-growing and hardy, growing close to treeline. Although its cones are diminutive, their seeds are big enough to be called “nuts,” and are a favorite of the Eurasian spotted nutcracker (and humans). Unlike the other pines featured here, its needles come in bundles of five.

Pinus mugo (Mountain pine)

Pinus mugo is a small, hardy subalpine species native to European mountains. Pinus mugo subspecies uncinata is the most common variety in the French/western Alps, and is sometimes considered a separate species, Pinus uncinata. It tends to be larger and more tree-like than its shrubby counterpart, Pinus mugo subsp mugo, which dominates in the east and is known as dwarf mountain pine. In its scrubbiest form, it can grow above treeline and in bedrock.

Pinus nigra (black pine or Austrian pine)

Black pine is only found in the eastern reaches of the Alps in the montane zone and below. As a species, it’s well known for its range of forms adapted to different parts of its range, with the Austrian populations (Pinus nigra subspecies nigra) tending towards shorter, stouter needles and more upright branches than more southerly and westerly subspecies.6

Coming soon

Conifers, part II: Cupressaceae (including junipers and a few exotic species), Taxaceae (yews), and Ephedraceae (ephedra, one of my favorite plants). Plus more about the phylogenetics and distributions of gymnosperms (and some bonus gymnosperms).

Glossary

Genus (plural genera), family, order, class: In taxonomy, progressively higher organizational levels above species

-aceae (ay-see-ee): Suffix of a plant family

Seeds: specialized containers for plant embryos

Spermatophyta: the part of the Plant Tree of Life encompasing plants that reproduce by seeds (as opposed to spores, like ferns and lycophytes)

Gymnosperms: seed plants without fruits, only “naked seeds” growing on bracts

Angiosperms: seed plants which enclose their seeds in fruits

Cones: specialized clusters of fertile leaves (bracts) bearing ovules or pollen

Ovules: female reproductive structures which become seeds when fertilized (actually a female gametophyte—see glossary for ferns)

Pollen: male gametophyte containing male reproductive cells

Vegetation belts: elevational zones found on mountains dominated by particular types of plants adapted to progressively colder and harsher conditoins

Treeline: the elevation at which the winters become too cold for trees to survive

Aspect: the direction of exposure of a slope (south-facing = more sun)

Boreal: cold northern regions dominated by temperate forests, especially conifers

Deciduous: a plant that loses leaves seasonally (in winter) and regrows them

Fascicles: precisely numbered bundles of needles found in Pinus

Although some conifers have gotten creative with bracts in ways that resemble fruits. See: yew, ephedra, ginkgo

Fauquette et al. (2018). “The Alps: A Geological, Climatic and Human Perspective on Vegetation History and Modern Plant Diversity” in Hoorn et al., Mountains, Climate and Biodiversity.

Just a handful of other conifer species are deciduous, including dawn redwood (Metasequoia, from China but used as landscape trees elsewhere)

da Ronch, Flavio & Caudullo, Giovanni & Tinner, Willy & de Rigo, Daniele. (2016). Larix decidua and other larches in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats.

John Henslow, founder of the Cambridge University Botanic Garden and mentor to Charles Darwin, planted a display of regional variants of Pinus nigra along the Main Walk of the entrance to the Garden in the 1840s—a fine example of his ideas about intraspecies variation according to environment.

Gymnosperms are such a weird and fascinating group of plants! Also I love pinaceae!

Great article super interesting I love gymnosperms and ginkgos are sooo weird they are the only living member of their genus, family, order, class, division! Ginkgo trees have been around for roughly 270 million years and barely changed!