Note: If you haven’t read my overview of plants in the Alps or my post about the Tree of Life and you have a minute, they are recommended though not required reading for this post.

How would you organize a book of plants found in your region? A casual field guide might be organized by flower color, leaf shape, growth habit or some other simple diagnostic. A plant atlas might be organized by location, altitude, or habitat. A forager's guide by season, culinary or medicinal properties.

A Flora—the book incarnation of a flora1—is organized by ancestry.

What is a Flora?

A Flora differs from a practical field guide in that it attempts to classify all the plants in a region (its flora), usually targeted at trained plant nerds who have the expertise to navigate a labyrinthine, though logical, identification table called a dichotomous key. As a result, a Flora is a tome, or several; you don't typically lug it to the field with you, but bring specimens back to the Flora.

The dichotomous key, a choose-your-own-adventure of sorts, poses binary questions about your specimen's characteristics that start broad (does it have seeds or spores, does it have needles or broad leaves? go to page 45 or else 115), get increasingly specific (does it have four or five petals, are the leaves opposite or alternate, does the stem have hairs, are the stamens and style exserted from corolla) and eventually, hopefully, winnow the possibilities down to your species. (You can give one a spin here.)

These questions are essentially traversing you along the plant tree of life. Each question takes you down a branch where a plant lineage took two different morphological paths a very long time ago. (It's not really so one-to-one, but generally holds true at the higher levels of hierarchy.)

Plant families and their tree

You can shortcut your plant key if you're conversant in the core organizing unit of this hierarchy: the plant family. In the nested groupings from vast Kingdom (or vaster Domain) to granular species, families are at a sweet spot somewhere in the middle. They're broad enough to be a tractable set to rifle through, if not at a glance, then at a steady sweep—roughly 600 of them, which may sound like a lot but it's a sight fewer than 400,000 (and if you're not in the tropics, that narrows it down). They're also specific enough to be a coherent, concretely recognizable group: they share, indeed, family resemblance. Even if you haven't memorized the features that define a family, you probably have a sense for what makes an orchid, or a daisy, or a rose. If so, you have an organizing image to begin gathering in its relatives.

I was formally introduced to the concept of a plant family in my second year of college, in one of my favorite classes of my college career, Plant Diversity. I remember how it took me a while to get my tongue around the telltale, vowel-drunk suffix of a plant family: "-aceae"—which scientists pronounce a multitude of ways but I mostly hear "ay-see-ee" with a glottal stop between the ‘ee’s.

Orchidaceae. Asteraceae. Rosaceae.

My Plant Diversity course used the classification hierarchy as a framework for learning the story of plant evolution, and vice versa. In my Tree of Life post a few months ago, I described it as a walk along the backbone of the plant tree of life. We see it in Figure 1 below. Here, way down the trunk, the ancestors of Embryophyta (land plants) colonized dry land. Further up, bryophytes (mosses, liverworts, and hornworts) split off from the tracheophytes, the plants that would evolve veins. Here the ancestors of lycophytes (clubmosses) survived the Carboniferous, and monilophytes (ferns) took off with their spore-laden fronds. Here the spermatophytes (seed plants) split into gymnosperms (cone-bearers, naked seed) and angiosperms (fruit-bearers, vessel-seed).2

And from there, what an explosion of branches to learn: the major families indexing the diversity of plant inventions within each of these groups (especially the prolific angiosperms, but the other groups have their star families too).

My upper-level Plant Classification course was where we got down to the business of learning the diagnostic features of (selected) plant families. We counted leaves and petals, memorized the shapes of fruits and the placement of ovaries relative to hypanthia, and looked at leaf hairs with magnifying loupes and trichomes under microscopes. But in the end, the most useful thing we mastered was gestalt: the overall impression of the collected features of a family, stretched or scrunched into whatever funhouse-mirror form a species might give it. One look at a plant with four-petalled flowers and flattened little discs for fruits, for example, and you know it’s Brassicaceae, a mustard. This is both a useful shortcut, and something of a superpower in the field—at least for a plant nerd.

Flora alpina

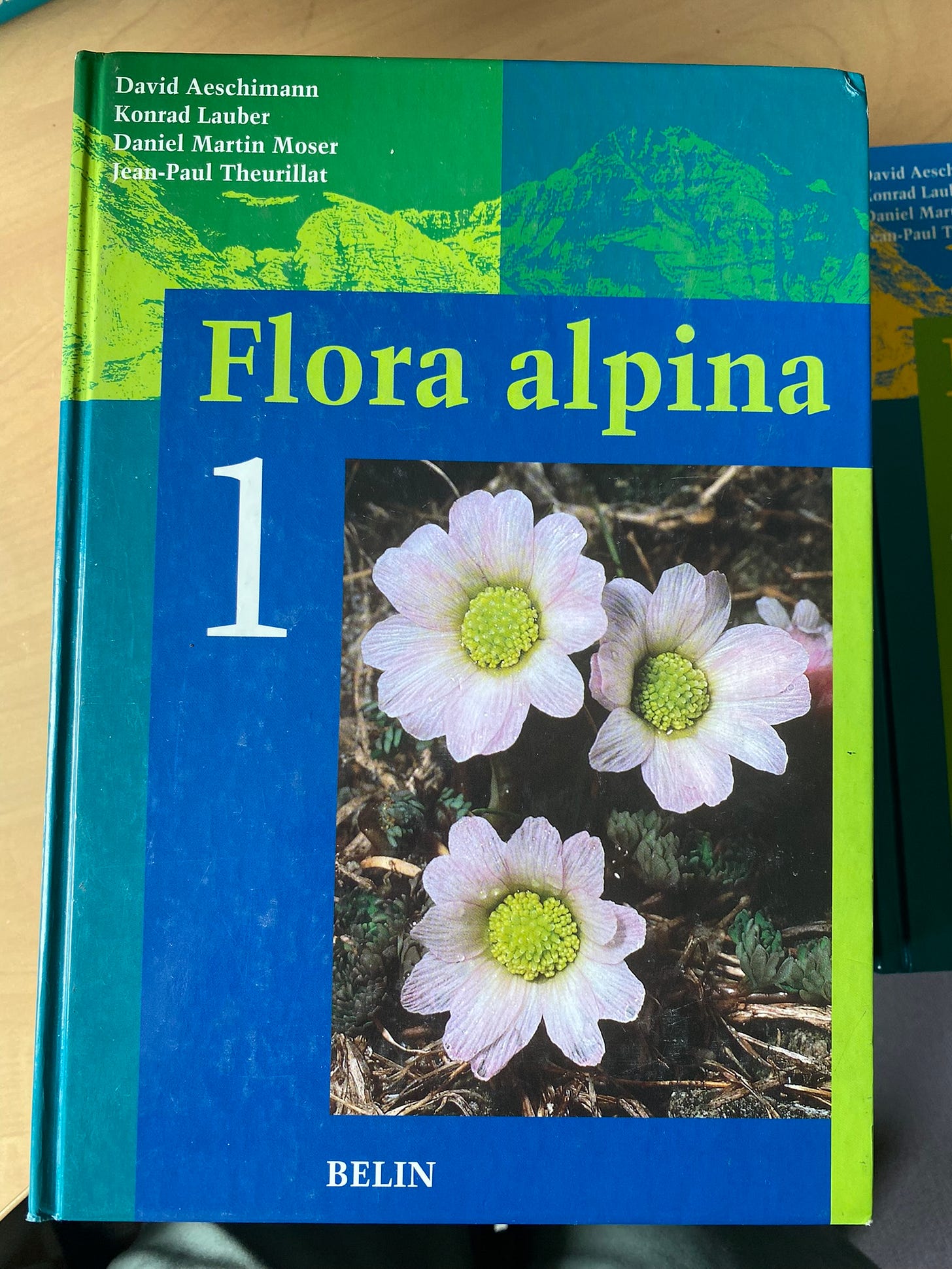

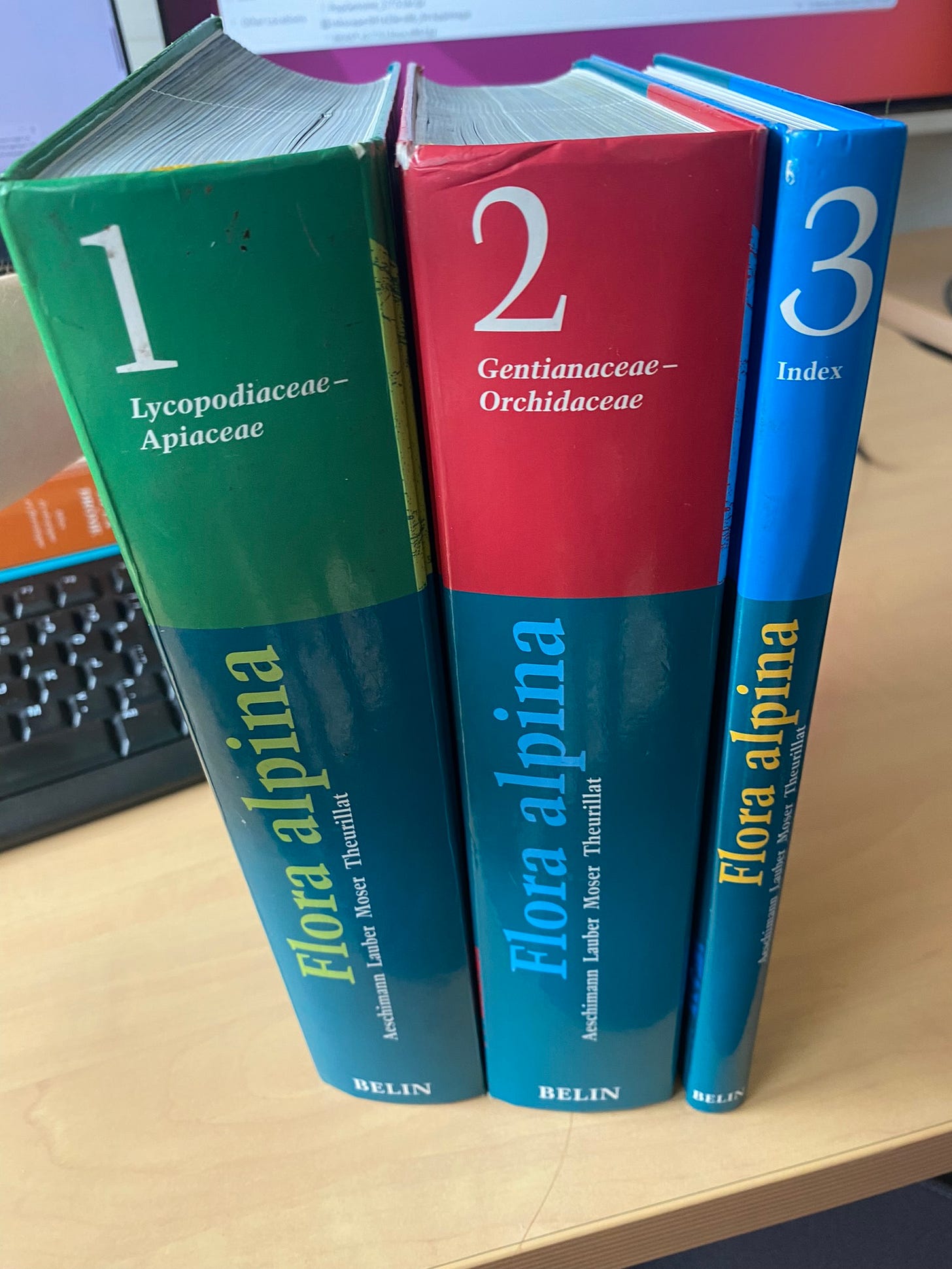

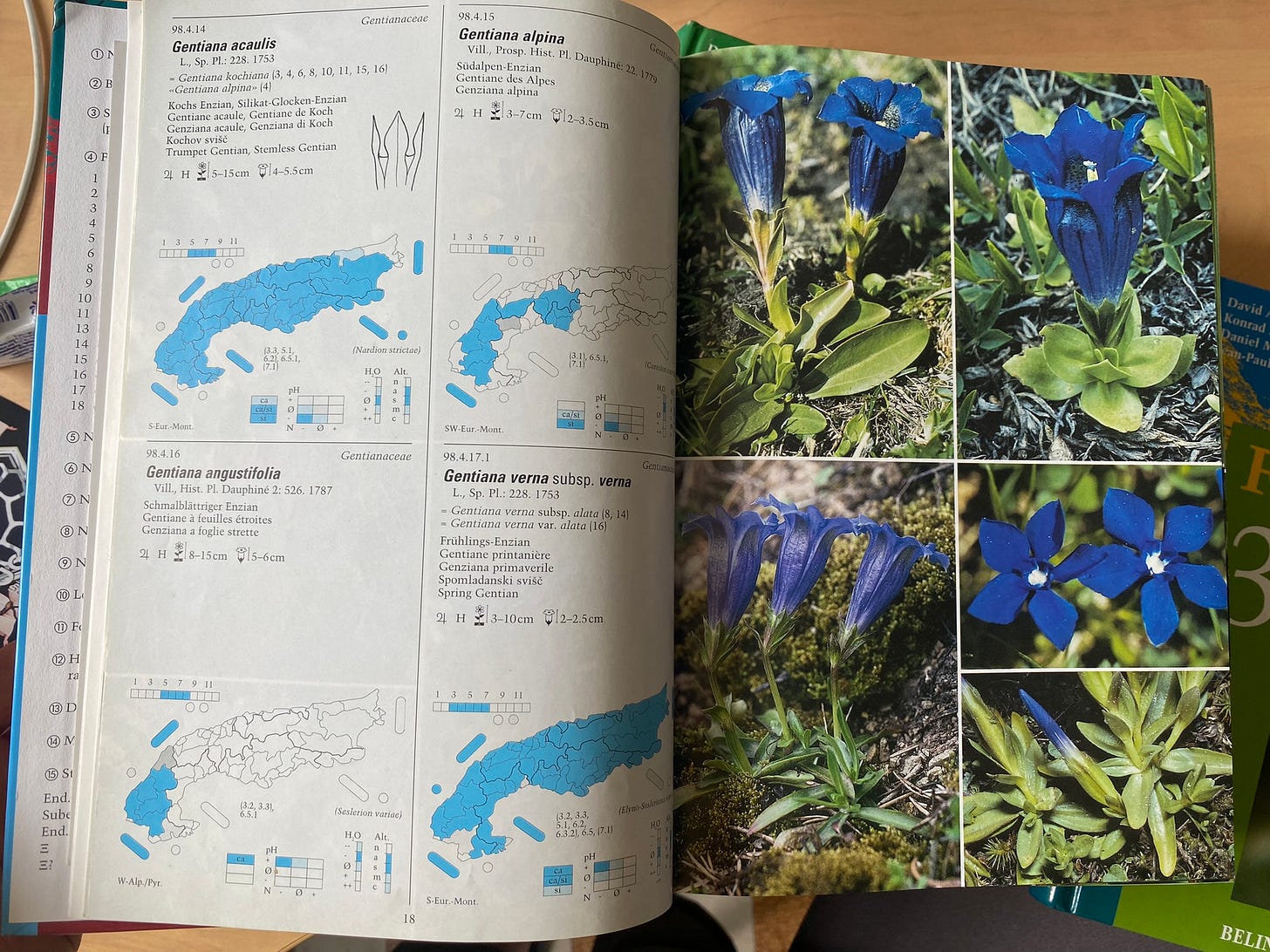

For a long time there was no comprehensive Flora of the Alps, one covering all the plant species across its many constituent countries and ecoregions. This was remedied in 2004, after more than a decade of international collaboration between botanists led by Geneva botanical garden researchers. The resulting three-volume Flora alpina is a sort of middle ground between field guide and traditional Flora, best described as a plant atlas. Every species is given a quarter page panel with a regional map full of shorthand ecological information, the common names in all the languages of the Alps, and a glossy photo. It doesn't have a dichotomous key, but species are organized by family, in plant-tree-of-life branching order.3

When I first got my hands on the Flora alpina, it was like Christmas. I haven’t been in the Alps long enough to know the flora very well at all, and this was the next best thing to hiking all over with a botanist to teach me. All 4,500 plant species, laid out in one big family reunion.

While I was getting so excited, flipping from family to family to find out who my neighbors are, which cousins of the plants I know from my past homes, an even more exciting thought coalesced in my mind. What if I shared this nerd-joy with everyone on Substack? I could make plant family profiles with star species and underdog species in the Alps, and what is it about that particular -aceae gestalt, and whatever other fun evolutionary and ecological facts spring up. I could even write plant family poetry (something I’ve been wanting to do for years)!

As I wrote in my overview of Alpine plant diversity, plant families are not evenly represented in the Alps, as they are not in the world.

Half of the 4,500 species are covered by only 10 major plant families, with the most (557) coming from Asteraceae, the sunflower family (also one of the most species-rich plant families in general); the other half includes over 100 plant families.

I haven’t sorted out which ones I’ll cover and how (e.g. how many posts will Asteraceae get?), but I want to make a start. I was tempted to choose a charismatic family—like Gentianaceae or Orchidaceae—and jump right in with pretty pictures. But eventually the evolution nerd in me won out and I’ve decided to go by the tree.

So I wrote this introduction to why the heck plant families, and what evolution has to do with it, and hopefully it makes sense and you’re all ready for me to start the series shortly with (drum roll please) our mysterious, erstwhile Carboniferous friends, Lycopodiaceae! Possibly bundled with some weird in-between fern families.

Meanwhile, if you want to find out which plant family you are, here’s a different kind of field guide from Kew Gardens. ;)

There’s flora as in flora and fauna (the plants and animals of a region), there’s your aunt Flora, and there’s the book called Flora of the Pacific Northwest. Or the Flora alpina, in this case.

See footnote 3.

One thing you learn in Plant Diversity or any other class based on phylogeny is that branching order is arbitrary; you can swivel around any subtree on its node and get a different order of tips. But it’s useful to think about the order that puts the “longest” branches on the outside—the groups that descended from the oldest evolutionary splits relative to the more recent splits. So we talk about lycopods and ferns before the numerous young inventions of flowering plants.

Good. I'm looking forward to this! And shall be cross referencing my copy of Keble Martin's 'Concise British Flora' (15 shillings in 1966 or so) properly arranged by plant families

I really enjoy how clearly and engagingly you describe and explain your world and your work Anne, thank you! I had a marginal role in the creation of a new flora in south west England some decades ago (though I'm not a biologist) and it was a life-enhancing experience! But that might not surprise you! If you're interested and have 20 minutes or so to spare you can read about it here! https://lizmilner.blog/2014/01/31/photographic-employment-4-natural-history/