Welcome back to the Flora alpina, an evolutionary tour of the plants in the Alps.

Previously in the series, we’ve gotten an overview of Alpine plant diversity, stood in awe of the Tree of Life, expanded on the meaning of plant families and Floras, and learned about the evolutionary history of plant sex (trust me, it’s relevant). So far we’ve explored the lycophytes, the weird ferns, the common ferns, the pine family, and other conifers.

The last episode was an introduction to the angoisperms, or flowering plants. (Recommended reading!)

Today, the first, “basal” representatives of the angiosperms.

What is a “basal angiosperm”?

Because I’m a nerd, let’s start with some evolutionary context. (Feel free to revisit the introduction to angiosperms for more of that.)

Recall how the lineages we’ve covered so far in this series—lycophytes, ferns, gymnosperms—represent branching points in the Plant Tree of Life: ferns split from the ancestors of gymnosperms before the latter evolved seeds, and as ferns didn’t happen to invent seeds independently, they now only have spores to work with. Similarly, gymnosperms split from the ancestors of angiosperms before flowers arrived, so they only have cones.

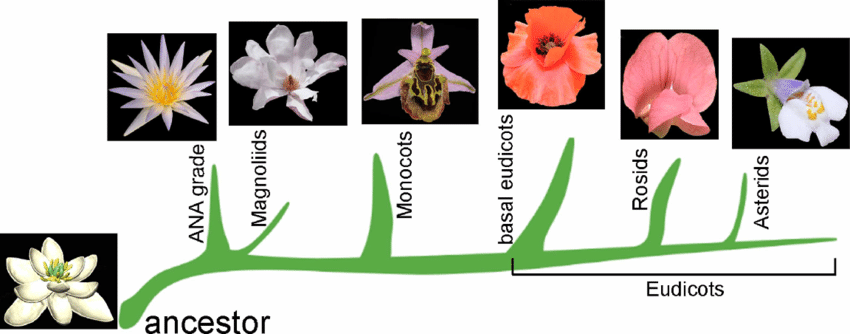

The same pattern can be seen within the angiosperm Tree of Life. There are branches that split from the rest of the angiosperm Tree of Life early on, near its “base”: after the invention of flowers, so they inherited flowers, but before the invention of other things, which they’re missing.1 Hence basal angiosperms. They’re also sometimes called “early” angiosperms (even though they’re technically just as modern as the others). And I might also call them “weird” angiosperms (like I did the “weird” ferns).

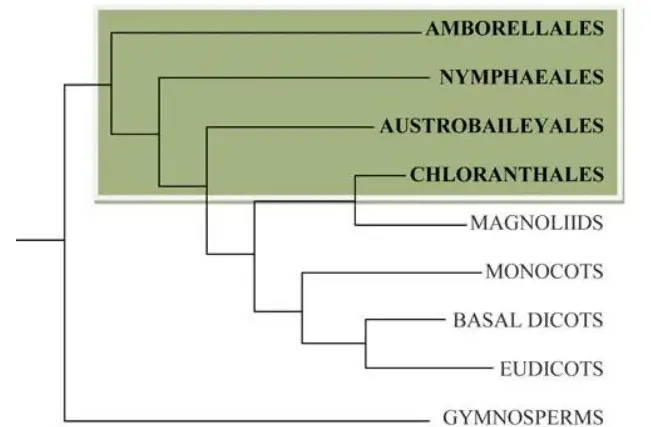

Basal angiosperms are on “spindly branches”: low in diversity and isolated from the bushy branches of the more recently diversified angiosperms (monocots and eudicots). Among these spindly basal branches are several very different groups, which I listed briefly in the introduction to angiosperms:

These “weird” angiosperms include Amborella trichopoda, an extra weird species from New Caledonia alone in its genus, family, and order; Austrobaileyales, an order including star anise (Illicium verum); Nymphaeales, the water lilies; magnoliids, comprising several orders including magnolias and laurels; and Chloranthales, a tropical order I know nothing about.

~ Optional phylogenetic interlude ~

As you can see from the first phylogeny below, where “basal angiosperms” have been highlighted in green, it’s not a neatly defined group, and magnoliids are not even always included under this banner. What matters is that they’re all quite separate from the innermost trio of branches that includes monocots and eudicots, where most angiosperm diversity is found.

~ End optional phylogenetic interlude ~

The rest of the post will highlight the two groups with native representatives in the Alps: the water lilies and the magnoliids.

Nymphaeaceae (water lilies)

Global diversity: 5 genera, 70 species

Alps diversity: 2 genera, 4 species

With apologies for the ridiculous number of vowels in that family name (“Nymph-ee-ay-see-ee”), this group should nevertheless be familiar. Water lilies root in shallow water and send leaves and flowers up to float on the surface.

Nymphaea

Flowers: showy with many parts

Fruit: globular, spongy capsule packed with seeds

Leaves: round with notch, floating

Nymphaea are classic waterlilies—the ones Monet painted.2 The abundant whitish-pink petals tend to “grade” into stamens (male parts that make pollen), i.e. transition gradually to stamen shapes closer to the center of the flower. This kind of gradation typically only happens in basal angiosperms.3

Most of the plant is edible, including the underground rhizomes.

Nymphaea alba occurs throughout Europe, and the similar Nymphaea candida is distributed even more widely across Eurasia. In the Alps, they stick to low elevations.

Nuphar

Flowers: cup-shaped, yellow, many parts

Fruit: urn-shaped capsule packed with seeds

Leaves: heart-shaped/elliptical with notch, floating

The cup-shaped flowers of the Nuphar waterlilies are less showy than Nymphaea, and the yellow “petals” giving them shape are actually the outer sepals, with the real petals stunted and hidden inside. The yellow, ribbon-y stamens are tucked around the central lobe of the gynoecium, i.e. a bunch of female carpels fused together into what will become the fig-shaped fruit.

Nuphar lutea, found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, is the type species of the genus (the one that was used to define it), and the other Alpine species, Nuphar pumila, was once considered a subspecies. They manage montane and even subalpine habitats.

Magnoliids

The magnoliids are a somewhat unofficial grouping of lots of weird angiosperms, of which magnolias are only one small subgroup. In the Alps we see several representatives of the birthwort family, Aristolochiaceae, and an introduction from the Mediterranean region, bay laurel. (We’ll sneak in a few ornamental magnolias as a bonus…)

Aristolochiaceae (pipevine / birthwort family)

Global diversity: 7 genera, 400 species

Alps diversity: 2 genera, 6 species

Aristolochia

Flowers: fused, inflated sepals form a long tube with flaring tongue; no petals

Fruit: round, melon-like capsule that splits into lobes when dry

Leaves: large and heart-shaped

Habit: Herbaceous perennial

Dutchman’s pipe, or birthwort, is properly weird. The tubular flowers resemble the kind of pitchers found on carnivorous plants, but these are for pollination, not meals. While carnivorous plants usually make pitchers from leaves, birthwort fashions a pollinator trap from reddish- or yellow-green sepals, the outer whorl of the flower, forgoing petals altogether. The flower gives off a tempting stink to attract flies, who are trapped inside for a nice nectar binge and a rubbing down with pollen until the hairs inside the tube shrivel, releasing them to find the next stinky flower.

The plant is full of toxins, leading them to be exploited in turn by several swallowtail butterflies, including Zernythia, whose caterpillars become toxic themselves by feeding solely on Aristolochia. Paradoxically, the plant also has a medicinal history (for example, its resemblance to a uterus giving it “expel the placenta” properties in olden-days medical logic, as well as the name birthwort).

Aristolochia clematitis is the most widespread species in the Alps. Others, like A. pistolochia (note the incredible rhyming Latin name; common name Spanish birthwort) and A. rotunda (smearwort) occur mostly in the west and south. All are low-elevation foothill residents.

Asarum europaeum (European wild ginger)

Flowers: small and fuzzy with partially fused purple tepals

Fruit: Globe-shaped capsule

Leaves: glossy, kidney-shaped

Habit: shade tolerant ground cover

Known as wild ginger because it vaguely smells like ginger (no relation), this plant is also toxic so probably don’t eat it.

Can be found throughout the Alps at low to montane elevations.

Lauraceae (laurel family)

Global diversity: 45 genera, 2850 species

Alps diversity: 1 species (Laurus nobilis)

A mostly tropical family of evergreen trees and shrubs, including bay laurel and avocado.

Laurus nobilis (bay laurel)

Flowers: small, cream-colored, clustered pairs

Fruit: black, single-seeded berry-like drupe

Leaves: Spear-shaped, glossy, robust, pungent

Habit: Evergreen tree

Bay laurel provides the bay leaves you put dutifully in your soup while wondering what exactly they contribute; also laurel wreaths (another common name is “victor’s laurel”). Technically, bay laurel is native to the Mediterranean region, with its presence in the Alps marked as “exotic” in Flora alpina. But it’s neighborly and widespread enough (at low elevations) to note.

I encountered one recently (in the Mediterranean, not the Alps) and was pleasantly surprised by the rich perfume of the leaves, which comes from aromatic oils and is apparently much stronger fresh than dry.

Bonus: Magnoliaceae

In the gardens and urban forests of Alpine cities, the namesake trees of the magnoliid clade abound. These showy, many-tepaled flowers with spiraling stamens and carpels probably still resemble the early flowers that evolved to attract beetle pollinators before things like bees existed, but humans also love them. Though mostly native to Asia (with another center of diversity in North and South America), they grow fine in the valleys here. In Grenoble, I greedily document the spring abundance of flowering magnolia every year.

Up next in Flora alpina

Getting into the monocots with order Alismatales, including aquatic monocots and arums.

Glossary

Genus (plural genera), family, order, class: In taxonomy, progressively higher organizational levels above species

-aceae (ay-see-ee): Suffix of a plant family

Spermatophyta: the part of the Plant Tree of Life encompasing plants that reproduce by seeds (as opposed to spores, like ferns and lycophytes)

Gymnosperms: seed plants without fruits, only “naked seeds” growing on bracts

Angiosperms: flowering plants; seed plants which enclose their seeds in fruits, which form from flowers

Basal angiosperms: branches of the angiosperm tree of life that diverged early from the rest, near the base of the tree

Whorl: one of the four units of a flower (sepals, petals, stamens, carpels)

Sepals: outer whorl of flower which can be leaf-like or petal-like; collectively called the calyx

Petals: second whorl of flower that can be modified to aid pollination; collectively called the corolla

Tepals: in some flowers, petals and sepals that are undifferentiated

Perianth: sepals and petals (or tepals) considered collectively

Pollen: male gametophyte (see glossary for ferns) containing male reproductive cells

Stamen: male reproductive organ in flowers with anthers that produce pollen, held up by filaments

Androecium: all the male organs of a flower together

Ovule: female reproductive structure that becomes a seed when fertilized (female gametophyte)

Carpel: female reproductive organ in flowers, consisting of stigma that recieves pollen and a style that leads to the ovary

Ovary: the base of the carpel, containing ovules, which becomes the fruit

Pistil: one or more carpels

Gyonecium: the combined female reproductive parts of a flower (multiple carpels or pistils fused together)

Capsule: a type of dry fruit with several carpels that splits open to release seeds

Berry: a type of fleshy fruit formed from one flower with a single ovary

Drupe: a type of fleshy fruit with a pit

Rhizome: an underground shoot that can establish new vegetative growth

Habit: the overall form a plant takes, such as tree, shrub, or herbaceous plant

Herbaceous: lacking wood

Annual: plant life cycle finishes within one year

Perennial: plant persists from year to year

It’s kind of hard to summarize what basal angiosperms are missing, because they’ve all gone down different evolutionary paths. Some of them lack consistent flower part development; magnolias for example have spirals of many undifferentiated tepals, stamens, and carpels, while most eudicots have petals in sets of four or five and clearly defined whorls of stamens and carpels. The stems of some basal angiosperms have less developed water-conducting cells. And there are more obscure clues like missing chemicals or pollen shapes. But it wasn’t always obvious; at one point in history all plants with branch-veined leaves were classed as dicots, lumped together with the main group of what are now called “eudicots” to distinguish them from basal angiosperms (like magnolias).

Fun fact, the common name for water lily in French is nymphéa.

However, all flowers use closely related genes in different combinations to make petals and stamens which can easily be mutated and manipulated—for example, in garden variety roses, stamens have been mutated into petals. (See the ABC model of flower development)

I love the ‘ Optional phylogenetic interlude’! Great article as always, Anne