Dear friend,

This is a doozy of a historical post. After several weeks of research I’m honestly still dizzy from the rabbit holes, which I’ve tried to summarize as succinctly and engagingly as I can here. In any case, please feel free to take this a couple forts at a time, but don’t give up! The most interesting stories may even be at the end of the post—but I’ll let you be the judge of that.

A note: most of my information comes from the website of Fort du Saint-Eynard, a repository of painstaking historical summaries of all the forts and their contexts, written by Jean Azeau and others. I’ve linked the page to each fort from the headings, and any additional sources are linked in the text. Most of these are in French, but if you’re truly interested to learn more, in-browser Google translate is a modern miracle!

Photos are mine unless otherwise noted.

The year is 1873. The French have recently lost the war with Prussia, which made away with Alsace-Lorraine and unified into the German Empire under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck1. In Paris, the new Comité de défense is meeting to discuss the measures to be taken against incursions by their looming neighbor. The committee’s secretary, military engineer General Séré de Rivières, proposes a revolutionary new approach to fortification, to be implemented across the country. Rings of small, easily defended forts spaced at the range of the newly powerful rifled artillery, forts that create walls of crossed fire instead of stone, that are in strategic cahoots with the landscape and the sightline. The day of the bastion and the citadel is over.

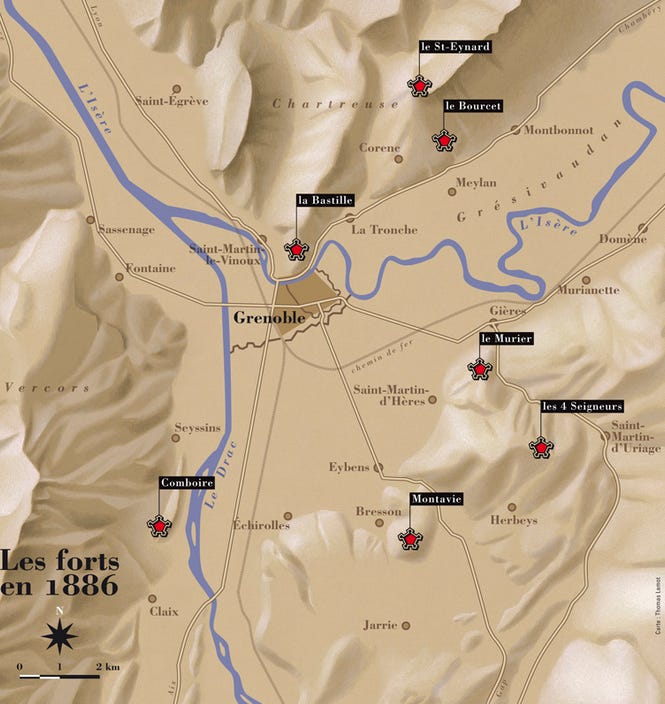

In Grenoble, garrison town of the Alps, the responsibility for implementing the new forts falls to Colonel Cosseron de Villenoisy, writer of defense engineering treatises. He takes his stewardship of the security of the Grésivaudan Valley seriously, though the enemy is more likely to be Italian than German. He assiduously selects the hills and ridges to be topped with forts to secure the tricky tight-walled Y with its passages funneling down from the Alps and northward to the plains of Lyon. There will be six forts realized, joining La Bastille, the bastioned fortress built by General Haxo thirty years before, to form Grenoble’s fortified belt.

Within decades, the forts will be outmoded by explosive shell artillery that can crumble stone masonry. They will never see the kind of combat they were intended for. But they will continue to live in the landscape: six stories of occupation, resistance, repurposing, restoration, celebration, and desolation. From one wall of Grenoble to the other; from 1873 to World War II to the nuclear age to the present. Stories still being told.

As a rule, I am not military-minded; my interest in the minutiae of battles and fervent side-taking is limited. Thinking deeply enough about the accoutrements of war is more likely to give me chills of dismay than thrills of fascination. But I am interested in history, and how you can read history in the landscape like fragments of a manuscript. War and the anticipation of it, political maneuvering and policy, geographical realities and cultural forces: all of these have coalesced into physical structures that linger and linger here, isolated, crumbling. And they are palimpsests, taking on layer after layer of the exigencies and interests of descendants.

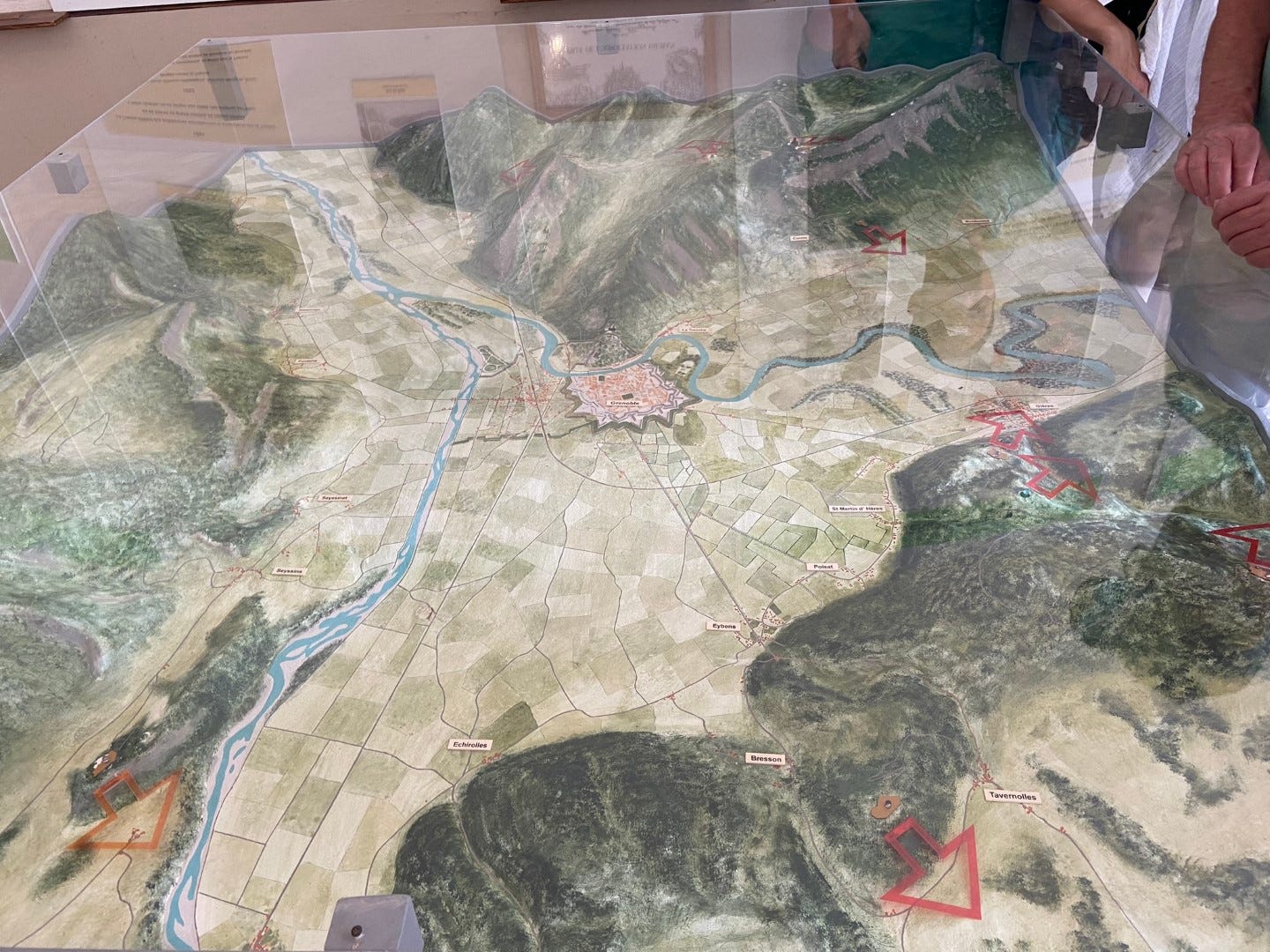

When I first visited one of these 1870s forts, Fort du Saint-Eynard, I had no idea there were more. I went to La Bastille, of course, the very first day I arrived in Grenoble, as do most tourists (read about my visit here). I became aware of Fort du Saint-Eynard more gradually. When I finally visited, one of the exhibits in the old barracks, titled “Ceinture fortifiée de Grenoble,” caught my attention, partly because I find the word ceinture (belt) somehow beautiful, and partly because there was a three-dimensional map of Grenoble studded with little lights representing forts (we were surprised the lights worked, but more on that later). So many of them! And so the seed of their stories was planted. Once I started digging, I was enthralled by how many branches those stories have.

Without further ado, then, the forts. There are the restored and displayed forts: Saint-Eynard and Comboire. There is the fort occupied by, it seems, the restoration company: Bourcet. There is the erstwhile-city-space, now mysteriously private fort, Mûrier. And there are the utterly abandoned forts: Quatre Seigneurs and Montavie.

Fort du Saint-Eynard

Named for a wandering Carthusian monk who died in England pining for his Chartreuse home, Fort du Saint-Eynard is by far the most vertiginous fort of the group. It’s perched on the edge of the most prominent cliff on the northeast side of the city (Mont Saint-Eynard), visible from the summit of La Bastille’s ridge (Mont Rachais). The sheer cliff facing Grenoble is totally inaccessible, but the backside of the ridge is comparatively gentle and populated by villages (and thus bus stops). An enjoyable randonée is to walk to the fort from the main village, Le Sappey, along the spine of Mont Saint-Eynard, with its plunging views over the valley.

The construction of the fort was understandably difficult, requiring new roads to be cut for the transport of lime, sand, water, and men, and for military personnel to supplement the crew of Italian emigrant workers. But it was worthwhile; the fort would protect the Chartreuse approach to Grenoble, rain down fire on any siege of Fort Bourcet below the cliff, surveil the valley, and operate the optical telegraph (with a cutting-edge crank-operated electrical motor) to communicate with the whole network of forts and beyond, even as far as Lyon. (Fallback system: carrier pigeon.)

Like the other forts, Saint-Eynard was not ultimately needed for defense, and its cannons were even dismantled and sent to the Eastern Front during WWI. The military lingered, installing a cable car for transporting equipment in the 1930s. During WWII, it was occupied by Italians, then Germans, and briefly toward the end, if Google translate hasn’t led me astray, by Resistance fighters as they harassed the enemy. The French Resistance will feature brilliantly in some other fort stories below, so keep reading!

Visiting Fort Saint-Eynard today is a study in restoration and a certain kind of local color. There is an element of romance, especially at the first approach from the hiking path, which takes you via a rocky tunnel blasted through the ridge before opening onto the stone-arched entry gate of the fort. The day I visited, the fort was open for the annual weekend of Journées européennes du Patrimoine, European Heritage Days. This meant there was a lot of activity—families, guided tours, and even a motorcycle convention which had parked their gleaming bikes within the fort—which tended to dissipate the historical atmosphere.

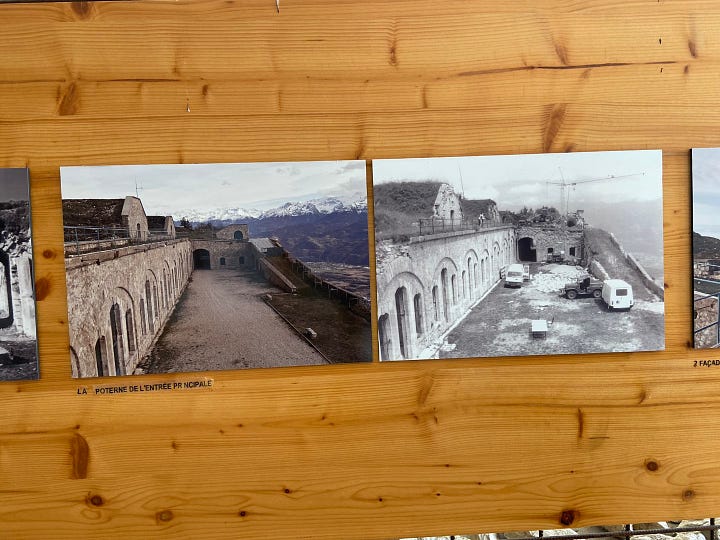

Nevertheless, the clean stone facades with their symmetrical arches, hunkered under cannonball-absorbing earthen roofs and trimmed with sky blue paint, are a testament to the restoration work that retrieved the fort from decades of neglect in the 1990s. One of the exhibits housed in the fort features before-and-after photos of the crumbling masonry and collapsing walls, and chunks of stone and timber that had been replaced with replicas. In some ways the restoration was as hazardous as the original construction: at one point, vandals even pushed the construction equipment off the ridge and it had to be rescued by helicopter.

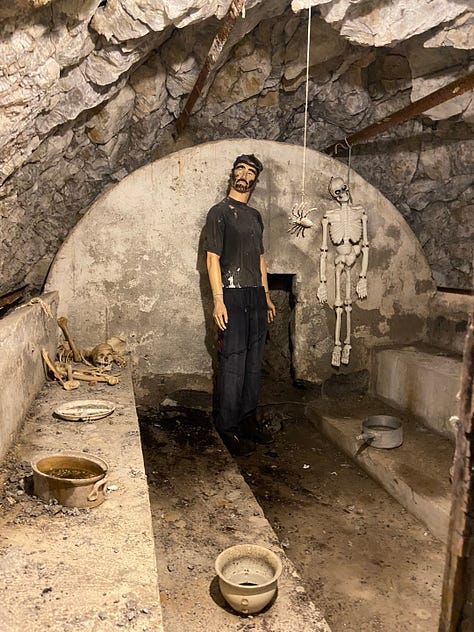

The other exhibits in the long, paired wings of the fort were…quaint. On one level, rooms were populated with old furniture and less-than-professional mannequins with felt handlebar mustaches representing telegraph operators, whiskey-drinking officers, and soldiers in nightwear standing by the Spartan wooden bunk frames. The holding cell even featured plastic Halloween skeletons (though there was no indication anyone had ever actually died in the cell). Upstairs, the plaster-walled rooms were lined with foamboard replicas of advertisements for railway travel, musical productions, teas, and cigarettes, intending to give an impression of the “actualités d’epoque” but coming across mostly as someone’s eclectic collection in need of a display space2. This vibe was even stronger in the room displaying someone’s diorama of WWI battles made from model train kit and craft materials. The exhibit on the ceinture fortifiée that sparked this post also had a dusty handmade look, hence our skepticism about the lights on the map of the forts. Only the restoration exhibit looked like it had been updated since the 90s. All of that said, it’s the same kind of volunteered passion that keeps this place in a living state, and there’s something to be admired about its earnestness.

We peeked into the colorfully and (as expected) eclectically decorated café, which occupies the same room that the military canteen did, but didn’t try the highly touted ravioles du dauphiné.

Fort Saint-Eynard’s most commanding asset is the view. It was hot and windy the day I visited, and the Belledonne peaks marked on the panorama board were hazy across the valley, but the warped and folded limestone scarps of the Chartreuse behind Mont Saint-Eynard were clearer, and just as arresting. A donkey and mule grazed amicably on the grassy earthen roof with the Chartreuse as their backdrop. Not far above us there were glider planes moving silently on narrow white wings.

I almost ended up having to hitchhike home from Le Sappey, but that’s another story.

Fort Bourcet

On a low rise at the base of Mont Saint-Eynard, Fort Bourcet is situated across the valley from Fort Mûrier, a twin in crossfire. Its name honors an 18th-century general who was an expert in alpine warfare, and surveyor and director of fortifications at Dauphiné, of which Grenoble was once the capital. Unlike the other forts, Bourcet seems to be its only name. All the others have a commonly used geographical name, and a second “Boulanger” name originating from a short-lived 1887 decree by the minister of war Georges Boulanger to rename all forts after military heroes.3 This was reversed by his successor less than a year later (after a tumultuous change of government), and yet the Boulanger names seem to linger as a kind of subtitle to the principal names. Bourcet owned land near Fort Bourcet, so perhaps the name doubled as geographical and honorific.

Fort Bourcet is the smallest, lowest, and closest fort to the main city; it didn’t need its own bread oven or infirmary since those services could be outsourced. Still, with Fort du Mûrier, it was a mainstay of the defensive plan for the Grésivaudan Valley, a name for the northeast river plain of Grenoble (the righthand branch of the Y) that morphed from Gallo-Roman terminology.

The fort underwent a similar trajectory of obsolescence and decay to Fort Saint-Eynard, and after one restoration company folded before finishing the project in the 1980s, the same company that had successfully restored Saint-Eynard moved in on Bourcet. As far as I can tell on Google Maps, this company, L’Entretien Immobilier, also called (or parent/partner of?) Technhistorique, now uses the fort as its headquarters. This seems fitting.

Fort de Comboire

Still against the west wall of the valley, we now rise to rockier hills south of the village of Seyssins (one end of the tram line C that passes by my place). The hills, known as rochers de Comboire, were a haunt of the French writer and wit Stendhal (born in Grenoble) prior to the era of the fort. I passed these well-wooded hills on the highway recently, and I peered up at them as long as they were in view and could catch no glimpse of the fort, as was surely the design. Its fire would have covered the base of the Y grenoblois, the valley of the Drac River.

The last of the six to be built, Fort de Comboire is well-developed with multi-floor wings and a robust cement counterscarp along its encircling ditch. (“Counterscarp” is one of the words I learned while researching the forts: scarp is the inside wall of the moat-like ditch, counterscarp the outside wall.) Walls are decorated with entirely unnecessary crenellations à la medieval castle.

The military held onto it all the way until the 1970s, when it passed to the ownership of the nearby municipalities. Despite some neglect and the use of its ditches as a dumping place for backfill, it seems to have kept in the best condition of the six. Now it’s maintained and promoted, as such places often are, by a volunteer association, Les amis du fort de Comboire, and is open on the first Saturday of every month. They have a bulletin called Le Clairon full of photos of the latest military reenactments and volunteer restoration work.4

Fort du Mûrier

Now we cross the valley, to the crossfire-twin of Fort Bourcet, nestled at the top of the town of Gières (the other end of the tram C line, and across a small valley from the iconic Chêne de Venon, which I’ve also written about). Mûrier can mean bramble or mulberry, but far from quaint, the fort was the most powerfully armed of the six. The stone used to build it, however, was not up to par, and walls began to collapse not long after it was built. The artificial cement used to patch them sometimes made the problem worse.

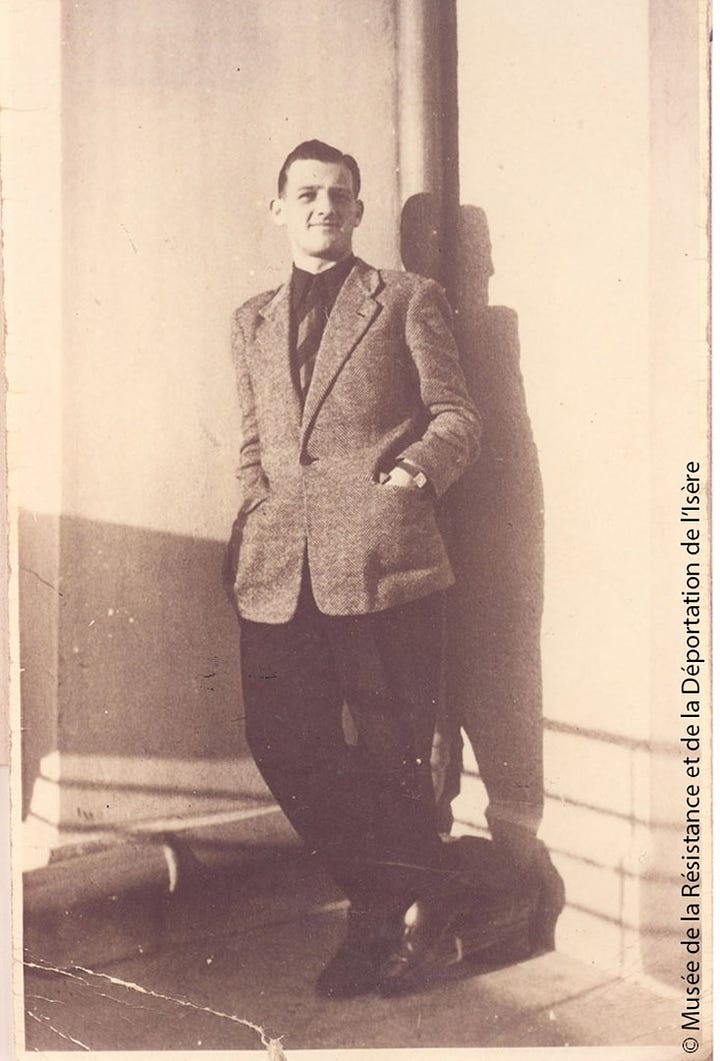

In World War I, Fort du Mûrier became a prison for German prisoners of war, who left graffiti and tallies of passing days on the walls. In WWII, the tables turned. At the start of the war, Mûrier was installed with anti-aircraft guns, but it soon fell into the hands of the Italians and Germans. The Resistance had a presence in the hamlet below the fort, and the Germans knew this, rounding up a dozen of them in early 1944 and sending them to concentration camps, from which only half returned.

But the Resistance persisted, and they needed ammunition. Only a few months later, armed Resistance fighters from Grenoble and militant refugees organized a coup de main, surrounding the fort and demanding their weapons “au nom de la résistance.” The few soldiers stationed there capitulated, and the resistance fighters managed to cart off 30 tons of munitions, even succeeding in warding off the German soldiers lying in wait for them on the road down. However, two Resistance fighters who had been waiting under cover were killed by the arriving reinforcements, and another was captured and deported (in French, déport usually refers to imprisonment in concentration camps).

Life after war for Fort du Mûrier had a period of color, when Gières took ownership in the 1970s, funded restoration, and artists set up workshops in the fort. There were annual heritage festivals and a Friends association. But now, the fort seems to be in private hands again, and stagnating. The Gières website only says “it was transferred by the city to a collective of occupants and local residents a few years ago.” Perhaps a financial necessity, and a reminder that restoration is not inevitably permanent.

Fort des Quatre Seigneurs

Deeper and higher into the Belledonne foothills is a desolate fort whose hilltop was once the crossroads of the lands of four lords (Gières, Herbeys, Uriage, and Eybens)5, and whose story is perhaps the most dramatic and mysterious of them all. It was built to protect the Uriage stream-valley cutting down from Belledonne (now the route to Chamrousse ski station), and also to liberate Fort du Mûrier below from any attacks coming from the Venon hills. Its first action was, of course, in World War II. It couldn’t withstand the Resistance.

The Resistance got their hands on this fort earlier than Mûrier, in a narrow 48-hour window in 1943 between the departure of the Italians in anticipation of their country leaving the war, and the arrival of the Germans to take over guard of the ammunition depot. The local Resistance pounced and trundled off as much ammunition as they could. In this case, though, they didn’t want to arouse the suspicion of the arriving Germans (who they knew had a thorough inventory). So the leader and detonation specialist, Paul Vallier, set up devices called pencil detonators to blow up the powder caverns they had stolen from. The wires were meant to be eaten away by acid over the course of two hours, but through error or imprecision it took several more—and not until after Vallier had gone back to replace them. As he sped away on his moped, he even passed the transport of German soldiers heading to the fort. Anxieties were high. But the explosion occurred just as the Germans arrived, blowing them up as well as the depot.

As it turned out, the German investigators blamed the Italians. Nevertheless, the Mûrier roundup four months later took many of the Resistance who had liberated that ammunition. Paul Vallier, whose real name was Gariboldy, was bounty hunted and assassinated three weeks after stealing 6 million francs from the Grenoble post office for the Resistance in 1944.

Although it was now missing a wing, Fort des Quatre Seigneurs was still largely intact, and the military used it for a training ground for another 20 years. In 1968 it was sold to what was then called the Grenoble Nuclear Studies Center, now part of the CEA (Atomic Energy Commission). References on the internet to what they wanted this isolated site for are somewhat vague—perhaps a laboratory for magnetometry, the controlled study of magnetic fields, especially useful for detecting nuclear submarines. But according to an online article from a local magazine, Le Postillon, the magnetometry facilities were in the hills on the opposite side of Grenoble until the 1980s, when the arrival of the tramway created too much magnetic disturbance. The one source who would give the reporter any kind of detail (they had tried the CEA, the Herbeys town hall, and the Herbeys flea market) suggested the lab had initially been focused on creating synthetic lightning. Another pointed to possible manufacturing of anti-submarine mines. In any case, CEA keeps to itself.

CEA gave up operations there when they built a better facility in Herbeys in 1993, but eventually decided (perhaps in order to sell it) that the site was in need of major “pyrotechnic depollution”—that is, removing old munitions and mines. This apparently took years and millions of euros, and until 2017 it was a high-security site, including the airspace above it. (My question: was Quatre Seigneurs really the only fort that merited this kind of cleanup? If the other forts haven’t been triggered in all these years, was this cleanup really needed?)

Since then, however, the fort seems to have been left to the whims of both the vegetation and the trespassers. My friends and I joined those ranks last week, braving the deepest, darkest corridors of this fading place. For that report, you will have to wait until my next post, as this one is already much too long.

Fort de Montavie

At last, we are closing our ceinture of forts, atop a moraine two hours’ walk southwest from Fort des Quatre Seigneurs. Fort de Montaive is across the base of the Y from Fort de Comboire, but would not have crossed fire with Comboire; rather it patrolled the southerly routes coming from Belledonne, e.g. via Vizille.

Nothing stands out in the history of Montavie. Like the others, it lapsed from artillery to depot to occupation to training ground, then was sold to the two municipalities whose shared border split its grounds, and was left alone. In 1998, an architecture student wrote a restoration plan for transforming Montavie into an equestrian center, but although it may have been architecturally viable, no funds were forthcoming. Parts of the buildings have been demolished for safety reasons, but most of it is left, like Quatre Seigneurs, to the plants and the taggers and the Airsoft players. Online photos show low walls and gaping arches overgrown by trees and ivy, dark dank corridors and trash. Montavie’s apparent fate is also how historian Jean Azeau described Quatre Seigneurs:

« Enfoui sous une végétation plus en plus dense, le fort aura bientôt disparu et ne sera plus qu’un amas de pierres éparpillées sur le sommet. »

“Buried under increasingly dense vegetation, the fort will soon have disappeared and will be nothing more than a pile of stones scattered on the summit.”

Perhaps six (seven) forts in one city is too many to hold the attention of the public, and perhaps we only need to hold on to one or two remember the past. Maybe the process of reversion to nature is itself a worthy story, instructive, even beautiful. A reminder of just how much our built landscape relies on continual human input, and how it will all one day end up.

What do you think?

The year of German unification (1870/1871) under Bismarck is one of the key facts I happen to remember from my Advanced Placement European History class in high school…so I didn’t even have to look that up, booyah!

Admittedly I did enjoy these posters, even if they were a bit of a tangent.

Boulanger’s nickname was “General Revenge,” if that tells you anything.

The website of Fort du Saint-Eynard, talks wistfully about some potential exhibits about Stendahl and cement manufacturing that had been stalled, but the article doesn’t seem to have been updated since circa 2000, so I’ll have to go check out Fort Comboire and see what they’ve done with the place. I think there’s a large relief map of the fort and replicas of cannons.

The Boulanger name of Fort des Quatres Seigneurs caught my attention due to the birth and death locations of the honoree: Aubert-Dubayet, born in La Mobile, in the colony of Louisiana, on August 19, 1759 and died in Constantinople on December 17, 1797.

This is a post to savour; so interesting. And great photos. Looking forward to learning more. And the less-than-professional mannequins are terrifying.

Anne this is marvellously rich in fascinating historical facts, I can’t even begin to imagine how long it has taken you to compile but thank you... I wait in anticipation for the next chapter!