The stone wall is tall and solid, and trees grow on top of it. From the street, it’s impenetrable. On Google maps, it’s a dense, misshapen patch of unlabeled green about the size of a small city block. Not a straight line of a wall, but a polygon.

Whenever I passed—which was often, as the wall is only a few minutes’ walk from my apartment—I would peer up at it, stymied by its blankness, put off by the unidentifiable heaps and tarps in the shady recesses where the wall angled away from the street. I made assumptions. It’s a military property, I thought, a storage bunker1 shrouded by trees from civilian eyes. Off-limits. And I walked on.

For nearly two years, this was as far as my assumptions got me. Then, one day, I went on a jog on a city path around the graffitied backside of the wall. I saw movement and looked up. Someone was walking their dog on top of the wall.

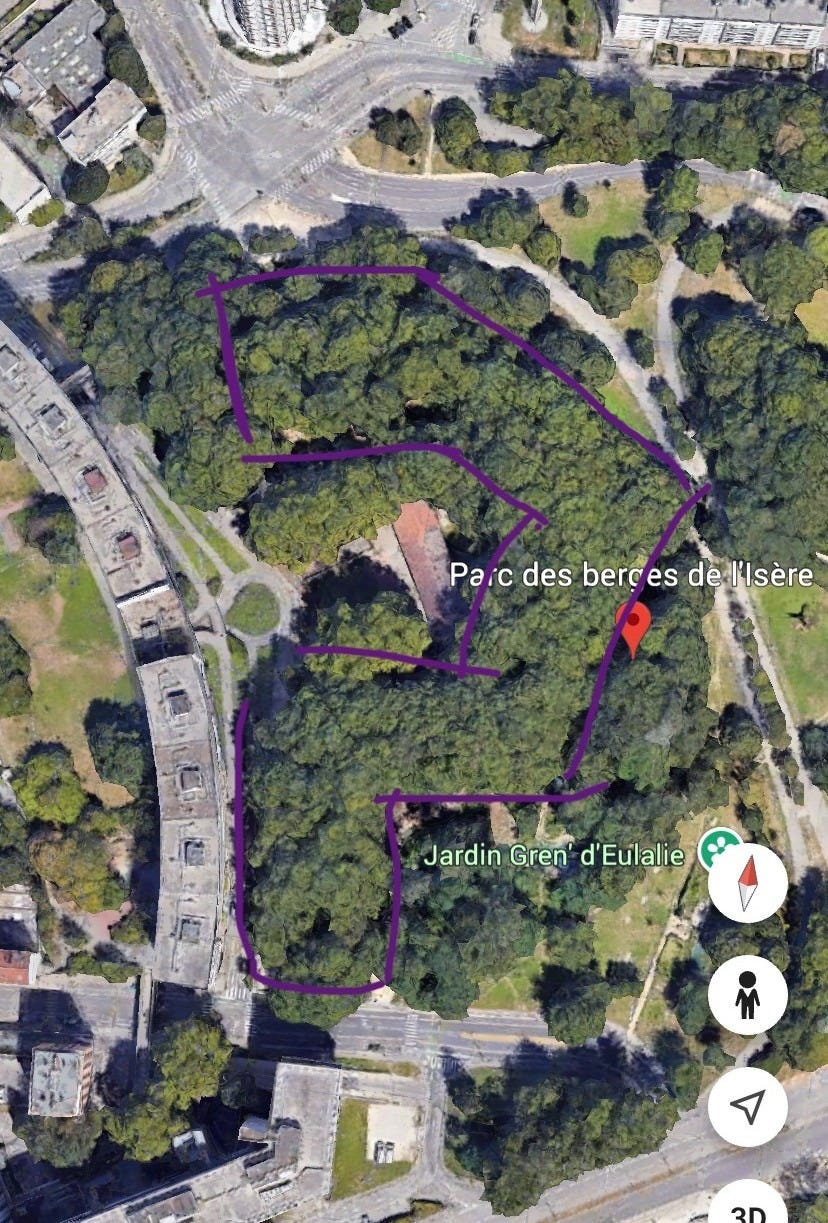

It didn’t take me long to find the perfectly accessible stairs, wide, worn boards embedded in dirt. The wall, it turned out, was a city park: a woodsy semi-circle ringed with multi-leveled dirt paths. Nestled down below, in the semi-circle’s heart, was a basketball court and a low-slung, identifiably old building painted with civic murals.

I walked under the bare trees with the tingle of portal fantasy in my veins2, noticing strange and tell-tale vestiges of stone and brick and rust in the scruffy undergrowth. I paused by a filled-in stone archway with twisted, rusted bits of metal jutting out from among the moss and trailing asplenium ferns, found a chink to peer in, saw nothing but dark hollowness. I looked closely at another bit of wall and found “1876” carved on a brick in convincingly antiquated lettering.

I paced out the topography of the wall, trailing up and down the layers of paths and the scrambly shortcuts between them. I looked down into the shady recesses that I had vaguely feared and remained nonplussed by the mounds of earth covered with fraying tarps. (I later learned that this was a dirt bike park in winter hibernation.) I found the edge that looks over the street where I normally walk and, from the remove of height, remembered when I was just a passerby ignorant of this little world above.

I went down another perfectly available flight of stairs (this one, steep with narrow and uneven stone steps, was tucked around the corner from the street) to examine the streetside of the wall again. Here, the robust blocks are smooth and well-preserved with decorative stone cannons thrusting out along the top of the façade.3 There are doorways, but all are boarded up and heavily tagged.

I found an unblocked embrasure slit to shine my phone flashlight through, and all I saw was space and stone.

Video: peering inside the wall.

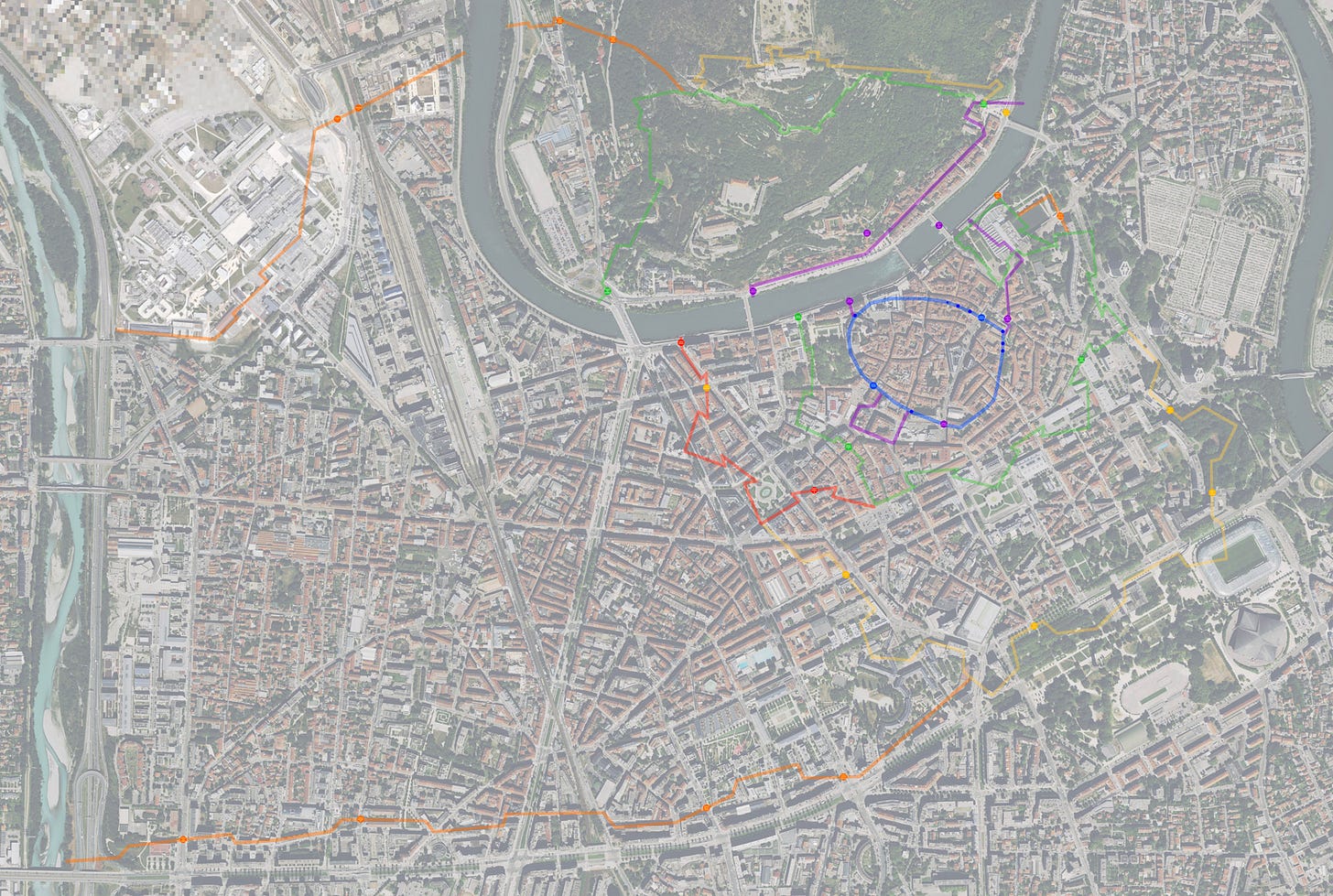

The next phase of my discovery process unfolded on the internet. As a starting point, I had only the name of the larger park encompassing this island of stone and woods: Parc des berges de l’Isère. The roughly bow-tie shaped park, strung along a curve of the river Isère, is part of a larger belt of green space around the edge of the city center, including the biggest city park, Parc Paul Mistral; the tree-cushioned housing complexes of Île Verte with its three hulking towers; the Jardin des Plantes across from the Hotel de Ville; and the Place de Verdun laid out before the departmental prefecture building. (See these places on map below.) The wall, whose irregular shape still didn’t quite make sense to me, makes up half of one flaring end of the bow tie.

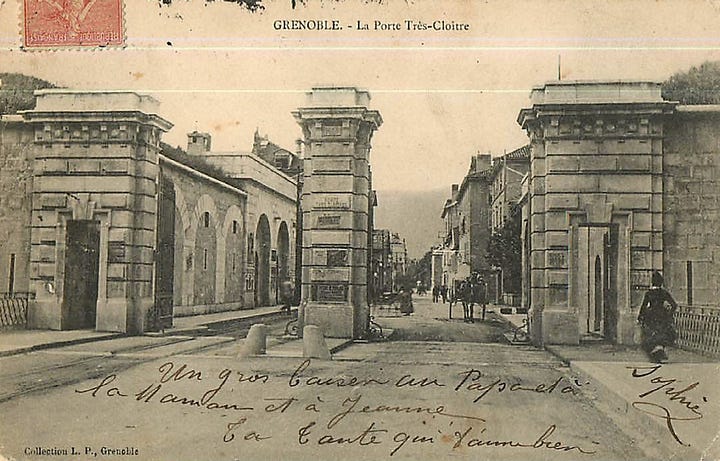

The name of the park got me nowhere. The trail of clues instead started with the Wikipedia page about the street tucked along one of the wall’s sides, the poignantly named Boulevard des Adieux. One hundred and fifty years ago, I learned, this street terminated nearby at the Porte des Adieux, one of the entrances to the city through the city wall. That gate led out to the city’s biggest cemetery, Cimitière Saint-Roch: Adieu. Down the road was another gate, Porte de Très-Cloitre.

But by the end of the 19th century, the wall was technologically obsolete, and the new tramway couldn’t fit through the Porte des Adieux. By 1924, the wall was demolished.

Except for this bit. Bastion #9, it’s called. So, I had been walking on top of a marooned vestige of city wall.

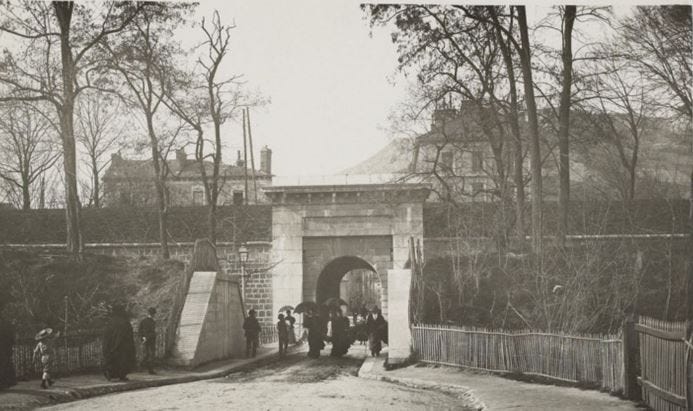

Photo source (a great website with lots more historical photos)

But this was not the wall; it was the penultimate wall. One of the walls that have layered like tree rings around Grenoble over the course of almost 2000 years. This wall, the enceinte4 Haxo, was built in the mid-19th century by the same General Haxo who built the Fort de la Bastille that overlooks the city. Like the Bastille, it was never attacked, and was only relevant for a few decades before it was outgunned.

I found a website with the outlines of all the old city walls traced on a modern satellite image. Suddenly, I understood the shape of the wall. It was perfectly obvious now: a pentagon, open along the bottom and hollow in the center. One of many such pentagons crenelating the map layout of the wall, multiplying the angles from which attackers can be fended off. A bastion, in other words. Now, perfectly gloved in trees, and alone in the city that has transformed around it.

The enceinte Haxo was an extension of an existing wall, a 17th-century one, precise and geometrically bastioned like an ornate star (green on the above map). It was built by another great fortifier, the Hugenot Duke of Lesdiguières, who made it his mission to prevent anyone from repeating his own successful attack on the town during the 16th-century wars of religion. And nested inside Lesdiguières’ wall: the ghost of the simple ring-ramparts of the 3rd-century Roman town Cularo (blue), just nine huddled hectares, plus a few medieval extensions (purple). (A ghost only rediscovered in the 1960s.)

Under threat from the neighboring Savoyards, Lesdiguières’ wall was extended (red-orange) once before Haxo, around 1700 by Vauban5, the “greatest military engineer of his time” who went around France improving fortifications . In the 1830s, Savoie was still a threat. With his wall (yellow), finished in 1836, Haxo doubled the area of the walled city to enclose the new southern suburbs.6

Then, in 1879, when walls were already becoming irrelevant and Grenoble’s new contingent of crossfire forts were under construction, the last, most ambitious wall began. It stretched in long parallel lines7 from the enceinte Haxo and the shoulder of the Chartreuse all the way to the western border drawn by the River Drac. It was most likely never finished.

None of these walls remain intact, except in crumbling, camouflaged bits. Bastion #9 is by far the best-preserved bit of any of them.

To me, this is a miracle. 1836 isn’t so long ago for a stone wall, but cities are like anthills, constantly shifting. In the tranquil openness of Place de Verdun once stood a bastion of Lesdiguières’ wall. Parc Paul Mistral was laid out8 in the wake of the leveling of enceinte Haxo’s teeth. Better uses of space, to be sure; we live in a place and time where a city has no need to cower and bristle. And yet the walls, as traceries of history, meant something with their physicality.

Bastion #9 is standing only by the grace of city planners and developers and maybe historical preservation societies, I’m not sure—I don’t have this part of the story. All I know is that it’s been allowed to settle gracefully, organically, tree-shadowed, into the living topography of the city. It stands guard over a basketball court, the city-run woodworking shop inside the old military building9, a bike park, a community garden, trees full of birds, and its own stone bones of historical identity.

A few days after my first discovery, while cycling at night past the cannon-studded façade of the bastion10, I made another discovery. One of the boarded-up doors was open, light spilling out, and a sociable group of people in climbing gear were emerging. There was nowhere to stop, so I only got a glimpse, but it looked like the well-lit walls were lined with useful things. So, even the interior of the wall has not been left to moldering emptiness. Bastion #9 has something like a soul.

Bonus photo: The bastion is connected to an apartment complex across the Boulevard des Adieux by a bridge, from which there’s a nice view of one of the towers of Ile Verte.

what is that? Idk, I made it up

Discovering this park was like the inverse of my discovery of Cherry Hinton Chalk Pits in Cambridge, a nature reserve (ex-quarry) sunk into the ground instead of raised above it, but with the same screen of trees and strange distortion of space and portal-feel. I wrote a lyrical blog post about it back in the day.

I had surely noticed the cannons before, but while picking up on the military bit, didn’t think about the “old” bit long enough to consider that this wouldn’t be an active military site.

The first definition of enceinte is a protective, enclosing wall. The second definition is pregnant—the womb as wall.

Vauban also built a poudrière (powder magazine) that still stands, a sagging stone structure in the middle of some apartment buildings near the city center (another fun stumble-upon discovery). Apparently it was enveloped inside Bastion #10, but now only the listed building remains.

Today, most of greater Grenoble (including the Parc Paul Mistral, the university, my apartment) would be outside the walls.

The southern half of this last wall ran along what is now Blvd Marchel Foch, a major road.

Parc Paul Mistral was originally designed as the site for the 1925 Exposition internationale de la houille blanche et du tourisme or “International Exhibition of White Coal and Tourism,” referring to the hydroelectric power that had become one of Grenoble’s shiny new exports. The iconic concrete tower in the center of the park, Le Tour Perret (currently being majorly renovated), is a vestige of that exhibition.

This building is the site of an MJC (maison de jeunesse et culture?) which as far as I understand is like a city youth club or cultural center. The nickname of the center is “Le Bastion.” The woodworking shop has a website with nice photos of its serviceable equipment and handsome creations.

This facade is the one visible in the old photos of Porte de Tres-Cloitre.

Fascinating, thanks. They did like a bit of bastion building in the past didn’t they? The great bastions that greet visitors to the Grand Harbour in Malta are stunning but were not really used, the moment had passed! Still they are glorious!

What a fantastic discovery! Thank you for digging deeper and sharing your discoveries.