One of the best things my progress in French has unlocked so far is local bookshops.

On Christmas Eve, finally out of the house after a week of illness, I had decided—deliberately, for the first time—to go to one of the biggest bookstores in Grenoble, Librarie Arthaud1, because what a cozy Christmasy thing to do.

On my way there, however, I was stopped short by the sign for a different bookshop: Librarie des Alpes. A bookishly disheveled, hole-in-the-wall, faded maps and motley piles sort of place. And it was open.

Librarie des Alpes is what it calls itself: a bookstore of the mountains, especially the Alps, especially the local ones (“Dauphiné Montagne” is the window-lettered subtitle). We’ll sidestep the pun about mountains of books; the black-and-white photos and paintings and postcards of mountains high on the walls—Belledonne, Oisans, Ecrins, Mont Blanc—set the mood well enough. When I came in, the owner, a stocky gray-haired man, was somewhere at the back of the shop, and a smiling young woman appeared at another desk. They chatted easily together in French across the crowded space.

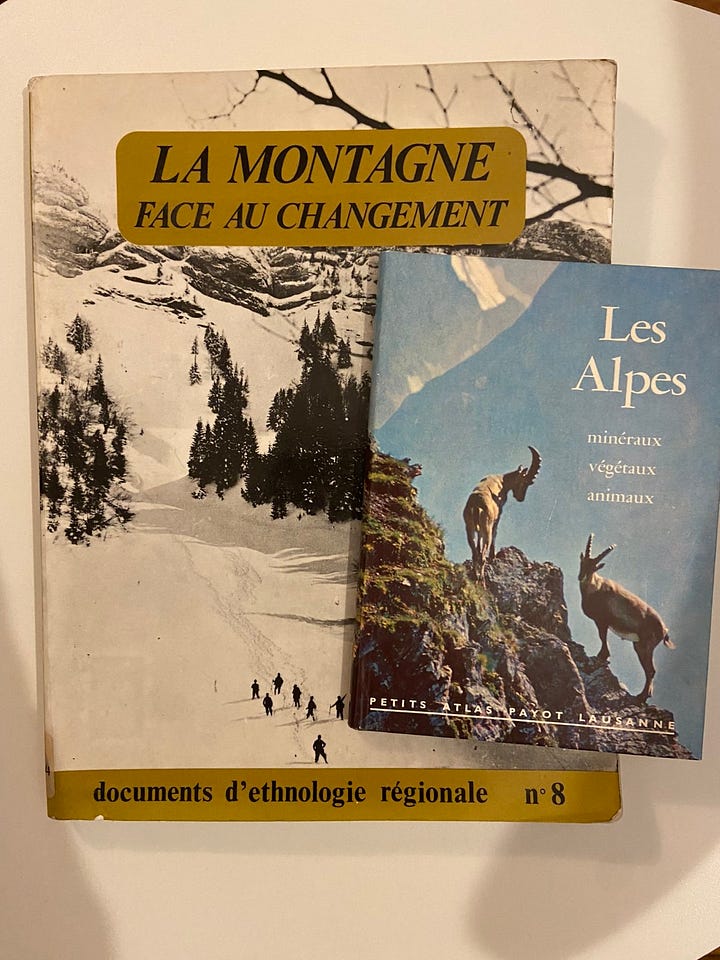

I browsed the small range of shelves for a while without any real sense for their organization. There were haphazard stacks of books on the counters, a wide range of ages, conditions, and subjects, though indeed mostly in the mountain genre: collectible pocket guides to alpine flora and fauna, antique cloth-jacket monographs, dog-eared paperback nonfiction from the 80s and 90s, new coffee table books of panoramic photography, climbing memoirs, children’s picture books, self-published historical novels about grenoblois figures. There were labels on some shelves, such as “Himalayas” or “Alpinisme,” but the contents didn’t always correspond. I even found some assorted secondhand sci-fi and classic novels unrelated to mountains.

And, as the walls advertised, there were maps, engravings, photography, postcards…

Several minutes into my browsing, the gray-haired man, whose name I would later learn to be Pascal, came up to me and said something friendly in French that I didn’t quite catch—it may have been, Was I just looking, but it had a teasing quippiness that I didn’t want to get wrong, so I just said my go-to apologetic phrase, Mon français est un peu limité, and he made a laughing gesture that could have been, Well then why are you still browsing French books, or maybe I was projecting that. In any case I insisted (in shy French) that I read better than I understand, and they laughed and seemed to get it. Later I asked the desk girl in French how much something cost and she responded in confident English.

She also informed me with the wave of a hand, when I asked where to put a book whose shelf I had forgotten, that there was in fact no real organization.

Although I was confident enough in my reading skills to buy something, I haven’t attained the skimming level, so it’s hard to quickly judge whether a book is any good. I hesitated, for example, over a 1970s history called Dames alpinistes, which was €30 and nothing special as a specimen, but an appealing topic—and then I saw that it had been translated from English so decided I would look for the original version elsewhere.

Finally, starting to feel the pressure of both time and being the only browser for the audience of two, I chose another semi-aged paperback volume of history: La montagne face au changement, no. 8 in a locally published series on ethnography from the 1980s with plenty of pictures. Given the publication date it may be something of a timepiece itself. Will I ever actually read a French academic treatise on the evolving social forces shaping mountain culture in the 20th century? I don’t know, but it’s a topic I think about often thanks to my research on land use change in the Alps. Call it a souvenir.

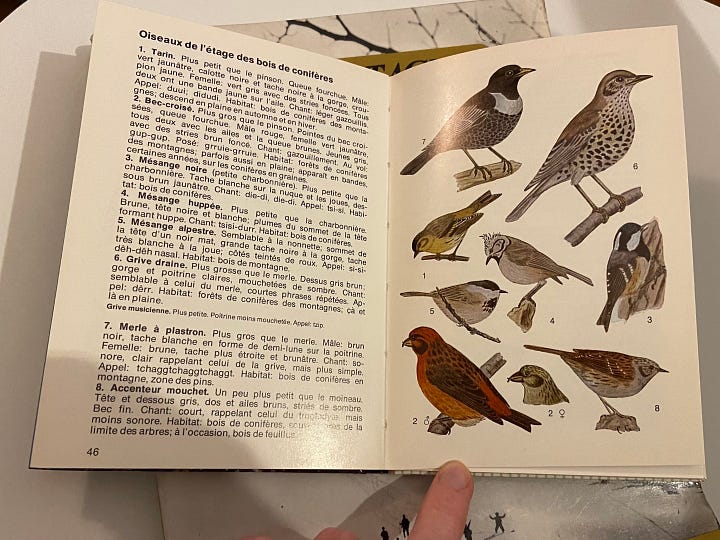

I also chose one of the little pocket guides, one including minéraux, animaux, et végétaux. A bargain.

While ringing up my books, Pascal made little jokes of sprinkling English words into his sentences (followed by Voilà, je parle anglais, non?), and also asked me if I had heard of a particular chanteur (was it someone singing on the radio at that moment? No idea), which the desk girl helpfully translated even though I had already understood and answered. Pascal entered the books painstakingly in a paper ledger, and meanwhile I looked around at the bowing shelves of antiquarian books at the back of the shop where I hadn’t ventured. I also noted down the name of an artist whose watercolor portfolio of Grenoble had surfaced atop a nearby pile, tempting me at the register—deliberate? Hard to say.

Pascal gifted me a postcard with the books, telling me it was by Samivel—had I heard of him?—un aquarelliste très connu2. It was a lovely snowy mountain landscape in soft blue tones, one I might have chosen myself, though I didn’t get a chance to say this properly because we were still going back and forth over the artist and the girl’s interjected translation3. A little linguistic collage.

I really would have liked to have an actual conversation with Pascal about his shop, how long it’s been there, how he sources and filters books, etc., but it was too hard in French. So it only remained to give a sort of awkwardly abrupt bonne soirée, as if cutting off a conversation that had never really started.

~~~

The conversation I wish I could have had, maybe someday will, was later partly supplied by Google and a trail of local magazine articles. This was when I learned that I had met Pascal Joffre, who owns the shop with his brother Olivier. The shop website, which is about as antiquated as you’d expect, didn’t tell me this; instead it offered an email address for Raymond Joffre, and when I googled him, found an obituary. He was Pascal and Olivier’s father, who, as a newly retired teacher, bought the shop in 19924 and ran it with gusto until he died of heart failure while hiking in the nearby mountains in 2021, aged 86.

Judging from the local press, he was an institution. In addition to Librarie des Alpes, he ran at least two different alpine-themed literary associations (Ex Libris Dauphiné and Ecrivains dauphinois), an alpine book fair that had just celebrated its 29th anniversary, and an alpinistic publishing label, Editions de Belledonne—named for the local mountain range about which he wrote a two-volume history. He called Librarie des Alpes his “danseuse,” a passion project5, I suppose, that cost him more money than it brought in (a question I admittedly had in mind while browsing the shop alone).

From interviews, it’s clear that Pascal and Olivier live in awe of their father. Having just retired from mountain guiding and forestry when Raymond died, they knew they couldn’t let their father’s danseuse die with him, though hey have left his other myriad projects to the associations he founded. They insist that they did, in fact, tidy up the store. And they enjoy prospecting for old editions like gold and talking to visitors about mountain culture. I aspire to be one of those conversational visitors, soon.

If you’re curious, here’s a nicely produced video of the Librarie des Alpes with interviews (in French).

P.S. Prepare yourself for more Grenoble bookshop content.

I will definitely write a separate post about Librarie Arthaud :)

Samivel painted the Alps and was “savoyard by adoption;” he died in Grenoble the same year that Raymond Joffre bought this shop. His nom de plume comes from The Pickwick Papers by Dickens.

She offered a translation of connu (“known”) that I momentarily heard as “no” and thought she was playfully contradicting him. She apologized for her pronunciation even though it was more an issue of what I expected to hear, a more common hiccup (in either direction) than truly incomprehensible pronunciation. (There was also the slight idiomatic misalignment that I’ve often noticed: English would prefer “well-known” to “known” in this context.)

There was a tantalizing passing mention of the bookshop’s Marxist past, post-war and pre-Raymond Joffre, but I haven’t been able to find any other information on that period so far.

If anyone has more authority on the connotation of this use of danseuse (dancer), speak up. My first thought was “mistress” but I don’t know if the innuendo is that strong.

This is lovely. There's something different about French bookshops that I really like. I'm not sure what it is, but it's there hovering in the wings of your essay. Thank you!

Oooh, I want to go!