Before plants had seeds, they had spores. Before trees had wood, they had scales. Before there was coal, there were lycophytes.

In this Flora Alpina series, we’re going on an evolutionary tour of the plants in the Alps. Previously in the series, we’ve gotten an overview of Alpine plant diversity, stood in awe of the Tree of Life, expanded on the meaning of plant families and Floras, and learned about the evolutionary history of plant sex (trust me, it’s relevant).

In this post, we’re finally diving into the Flora itself. As explained here, this evolutionary tour will be guided by plant families, as organized by the official Flora Alpina. This organizational paradigm also tells us a lot about history.

So, the lycophytes. Occupying the first few pages in the Flora Alpina1, this group represents a very old branch of the plant Tree of Life.

Today there are three surviving lycophyte families.

~ For vocab questions, see glossary at the end of the post ~

Lycophyte Factsheet

Lycopodiaceae (clubmoss family)

Worldwide: 16 genera, ~400 species

Alps: 11 species, no endemics

Selaginellaceae (spikemoss family)

Worldwide: 1 genus (Selaginella), ~750 species

Alps: 3 species, no endemics

Isoetaceae (quillwort family)

Worldwide: 1 genus (Isoetes), ~192 species

Alps: 3 species, no endemics

NB: When there’s only one genus in a family, that’s a good indicator of ghosts.

I.e., extinctions.

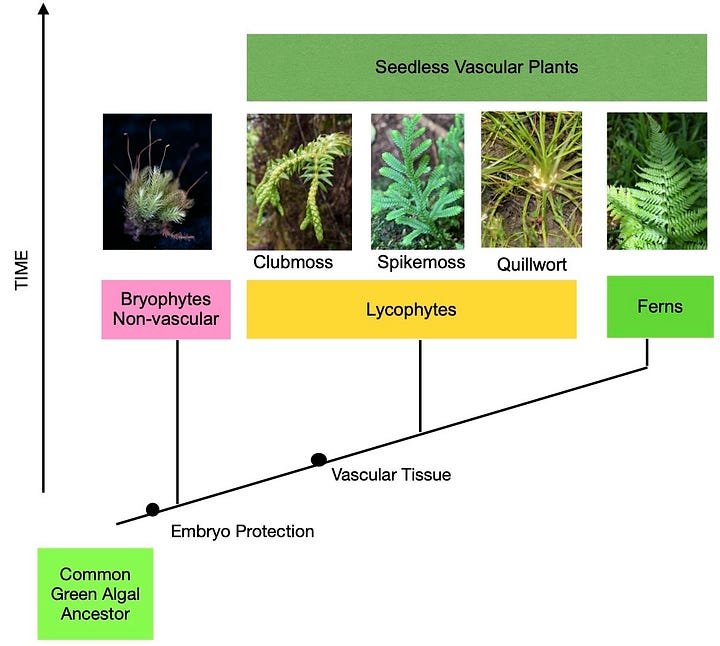

Lycophytes in the plant Tree of Life

Lycophytes in the Alps

I honestly don’t know whether I’ve seen a lycophyte in the wild. Today’s lycophyte representatives are unassuming plants, small and low to the marshy or shady ground. But they’re not necessarily uncommon. A few of the lycophyte species that occur in the Alps are widespread, given the right habitat.

I’ve been in some marshes and forests; maybe I unwittingly laid eyes on a clubmoss, its simple stems bushy with bristle-like leaves, blending into the general green. One detail might have tipped me off that the hypothetical clubmoss was neither a true moss nor a familiar seed-bearing plant: that would be the clusters of spore-laden leaves gathered into cone-like “clubs” at the tips, also called strobili.

It could have been an interrupted clubmoss (Lycopodium annatum) or an alpine clubmoss (Diphasiastrum alpinum), both Alps-occurring species from the Lycopodiaceae family. If the plant had chunky sporangia between scaly leaves, maybe a club spikemoss (Selaginella selaginoides), from the Selaginellaceae family. Probably haven’t seen a quillwort (Isoetes), a marsh species which looks a bit like a clump of spiky grass or an onion plant (but emphatically is not either of those; family: Isoetaceae) and is much rarer.

But if I did cross paths with a lycophyte, I wasn’t paying enough attention.

Ancient lycophytes

It wasn’t always the case that lycophytes were missable.

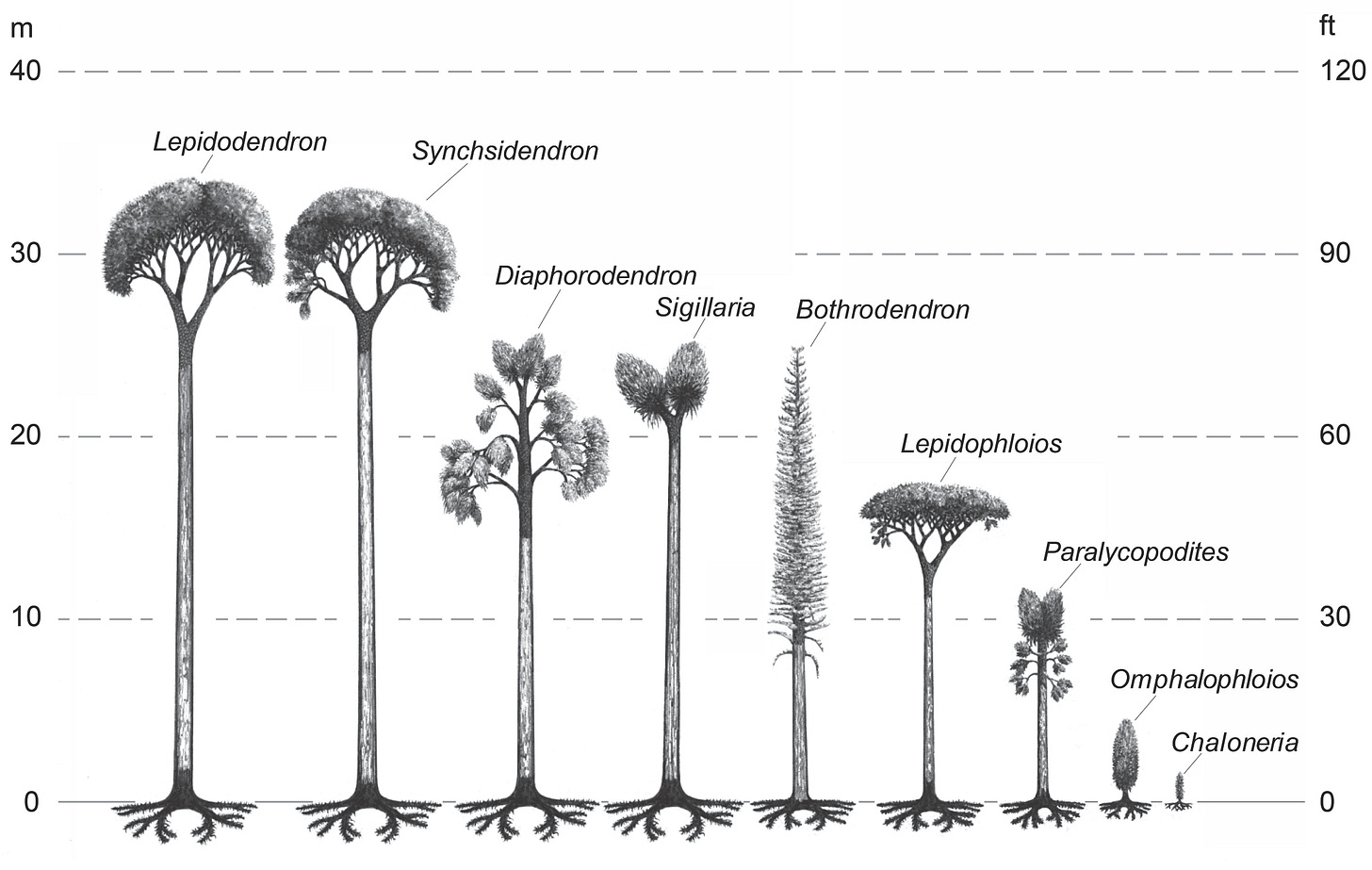

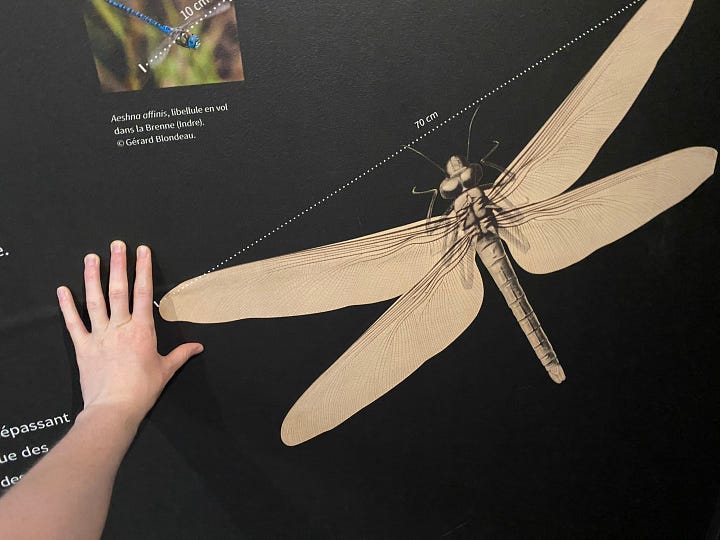

There was a time before seed plants, before dinosaurs, when dragonflies got nightmarishly big, and when ancestral lycophytes ruled the forest. During the Carboniferous period, 350 to 300 million years ago, lycophytes evolved a tree-like form that could grow up to 40 meters/130 feet tall. These slender, scaly-trunked, Dr. Suess-topped trees give the reconstructed Carboniferous swamp its surreal, jungle-y aesthetic. These were the scale trees.

Then they went extinct. Ironically, the Lycopodiales forests died off because of an ancient era of climate change, only to become the ghosts of another. After they sank into the peat, these lycophyte trees helped form the coal deposits that fueled the Industrial Revolution, and that we’re still burning.

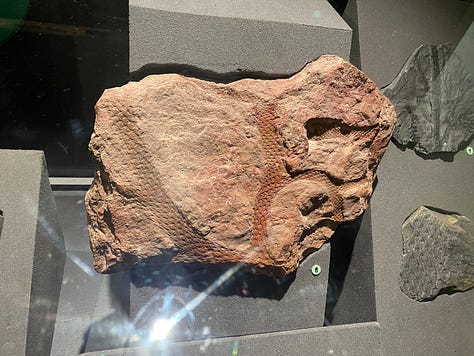

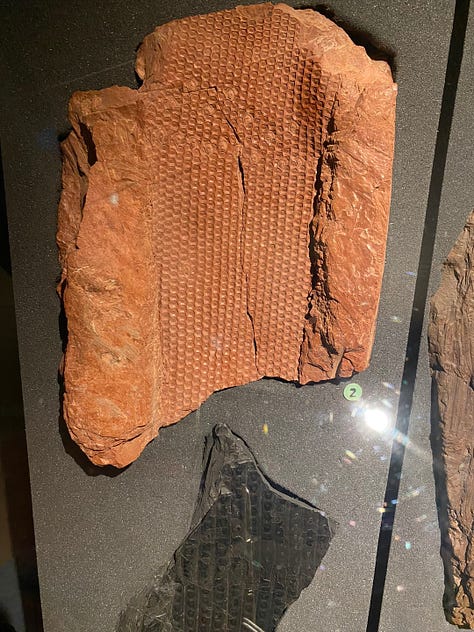

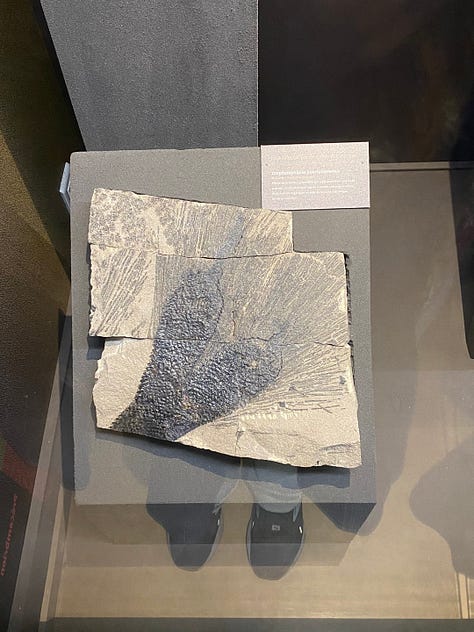

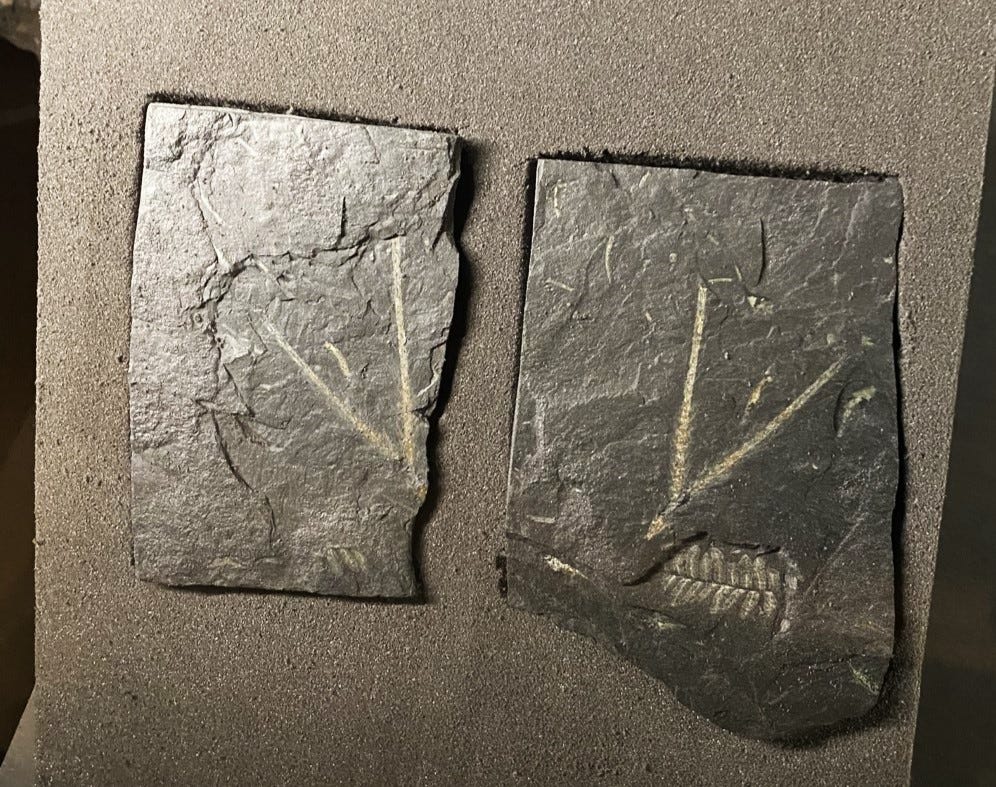

They also made stellar fossils. Thanks to such clues, we know that lycophyte forests once grew in areas now occupied by the Alps.

I discovered this via a beautifully curated exhibit about the Carboniferous Period at the local natural history museum in Grenoble.2

Here’s what I learned:

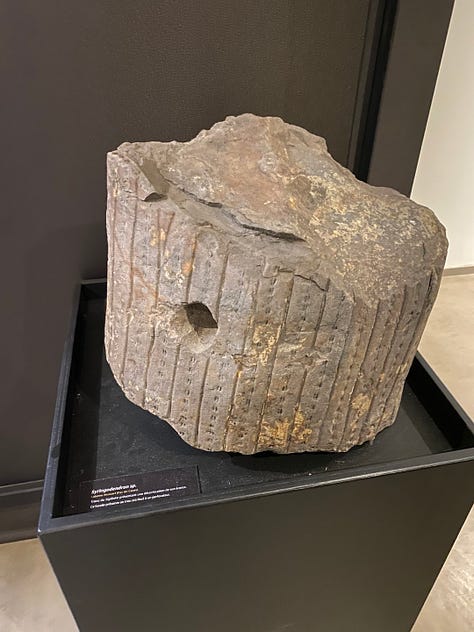

The Alps only began to form 20-30 million years ago. 350 million years ago, in the place of the Belledonne range that now towers over Grenoble, there was a lush tropical mountain range. In a lake basin under the surface of today’s Belledonne, trees called Diaphorodendron left imprints of their pineapple-like leaf scars arrayed neatly along their not-quite-wood trunks. There was also Lepidodendron, with branches like prickly snakes, and Sigillaria with finely hexagon-scarred trunk segments, and Omphalophloios with truly club-like strobili bristling at the end of its branches.

(The Belledonne fossil dig is near a town called Vaulnaveys-le-Bas. Imagine discovering this hauntingly gorgeous album of ghost plants from another planet in your backyard.)

Their neighbors included other early vascular plants (which will make appearances in later posts): arborescent ferns, giant horsetails, and proto-gymnosperms, with the earliest wood and seed-bearing cones. Some of the plant groups just starting to diversify, or not yet imagined, would have their day in eras to come. In the Carboniferous, though, the lycophytes were still having theirs.

Lycophytes today

Giant lycophytes like Lepidodendron are no longer with us. But as we know, the lycophyte lineage didn’t completely die out after the post-Carboniferous collapse of the swamp-forests. In Belledonne, for example, there are Carboniferous fossils of early members of a more modest genus that survived: Selaginella. And the ancestors of clubmosses and quillworts were somewhere, too. They made it onto the lifeboats.

What does this relatively small remnant branch of lycophytes have in common with those ancient fossils? After all, they’ve been evolving, albeit unusually slowly. They’re adapted to a planet that’s changed immensely. But their ancestors had already split from the ferns and gymnosperms. Thus, modern lycophytes have kept traits that defined the ancient lycophytes, such as their spore-bearing strobili. And they lack later innovations that define those other parallel branches on the plant Tree of Life, like seeds. (Here’s a deep dive into the evolutionary story of spores and seeds.) Lycophytes also never evolved wood or complex vein patterns in their leaves, which are still classed as single-veined “microphylls,” just like the fossil leaves.

Lycophytes do just fine this way. Selaginella, for example, is found on every continent except Antarctica. Clubmosses are abundant in tropical and temperate mountains around the world. These resilient lineages survived for a reason. But in terms of diversity and ecological dominance, lycophytes may never again balloon into anything like the prosperity they once had, or fill the space that other plants have claimed.

Bonus Wikipedia fact: Clubmoss spores make an explosively flammable powder that was once used in stage effects in Victorian theaters and for photographic flash powder. It can still be used as lubricant in latex gloves and condoms, and for physics demonstrations of sound wave movement and Brownian (random) motion of particles.

Up next:

Equisetaceae (horsetails), Ophioglossaceae, and Osmundaceae (weird ferns)

Glossary

Genus (plural genera): the organizational level above species and below family

-aceae: the suffix of a plant family

Endemic: only found in a specific region, e.g. the Alps

Phylogeny: a visual representation of evolutionary relationships in the tree of life, similar to a family tree

Vascular plants: Plants with veins, including lycophytes, ferns, gymnosperms (e.g. conifers), and angiosperms (flowering plants)

Spore: a reproductive cell produced by asexual splitting (again, lots more on that here)

Strobilus (plural strobili): a cluster of fertile leaves (sporophylls) where spores are found

Sporangia: sacs on sporophylls where spores form

Leaf scars: As non-wood “trees” like extinct lycophytes and tree ferns (both extinct and modern) grow, they drop their lower leaves, leaving regular scars. The built up stem/branch tissue is what forms the trunk.

Microphylls: small, simple versions of vascular leaves with only one vein

~ Let me know if you want to see a term added to the glossary! ~

The published Flora Alpina doesn’t include bryophytes, that is mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. They don’t have veins, unlike vascular plants. Despite this, they are fully plants and deserve attention. However, I’m sticking with the Flora’s organization for now, starting with lycophytes, the seedless vascular plants.

You can bet my first thought when I heard about the Carboniferous exhibit was “Ooh, lycophyte fossils!”

Giant dragonflies, Dr Seuss trees, and all those uses for clubmosses—a great post, Anne!

Anne I can only repeat Joy's comment - I loved (hung) on every word, ghost forests and giant dragonfly's? Wow...