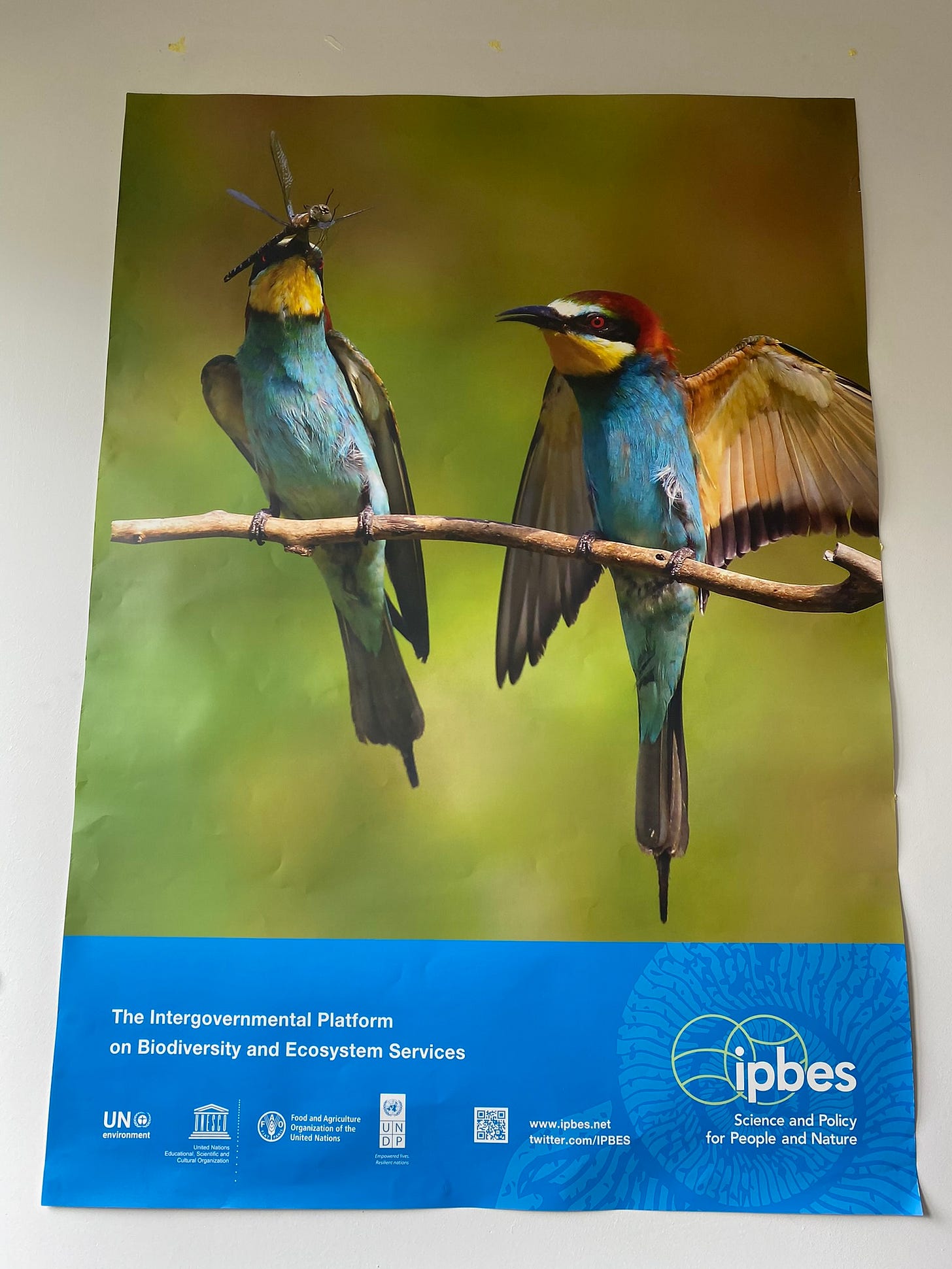

Above my desk in the Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine, someone tacked up a large poster from IPBES1 featuring a pair of jewel-toned birds perched on a branch. One has a dragonfly crammed in its curving beak; the other, wings spread in readiness, waits to accept the gift. Maroon eyes stare from black masks that streak back from the beak like war paint; geometric wedges of yellow throat and turquoise belly blaze from the page; tails dip to finely whetted points. They are magnificent.

I recognized them as bee-eaters, a family of birds I vaguely associated with Africa, with the implicit assumption that such bold, parrot-adjacent plumage would not belong to the temperate northern hemisphere.

Delightfully, I was wrong.

In the last week of May, Julien (naturalist extraordinaire) sent a photo to the lab Slack group alerting us to a colony of bee-eaters just up the river from us, in case we were interested. (I was.) The birds in the photo were the birds on the poster: not just any bee-eaters, but Merops apiaster. European Bee-eaters. Guêpiers.2 They do live in Africa, but only in the winter; in the summer, they breed just a fifteen-minute cycle ride away. I borrowed Julien’s binoculars and headed straight out after work to go add them to my birder’s life-list.

My bee-eater quest was a perfect, golden evening, and also my farthest foray up the river Isère to date. The river swathes through Grenoble and curves around the Université Grenoble Alpes campus, separated from my building only by the Arboretum and the bike path. I joined the bike path and followed it upriver.

The river path swung me close enough to the lush foothills of Belledonne that the mountains were briefly hidden; past the sheds where the trams of Grenoble sleep; through a poplar avenue framing a luminous field of new corn. When the path cut away from a sharp bend in the river, I had a clear view over the fields to the Dent de Crolles, the pyramid of rock that dominates the northern end of the long, sheer terrace of Saint-Eynard. The cuspid transforms continuously on approach, taking on new geometry, new crags and ragged hollows.

As soon as the path rejoined the river, I came upon a stretch of bare, steep-cut bank across the water. I heard the burbling communal song before I spotted them sailing to and from the holes in the bank, the perches in the trees, and the banquet in the air. There were dozens of holes, and at least as many birds soaring and perching.

Even without binoculars I could see the precise cut and flare of their wings like panes of stained glass; the sudden taper of their tails3; their kiting and fluttering.

With binoculars, I began to follow their flightpaths, crystalline and ecstatic against the sky, into the dazzle of the evening sun and back down to the shadowed bank. A few of them perched sociably on roots stringing out of the bank; a few others took to the trees on my side of the river, where I could gaze and gaze at their crisp, glowing standards of burgundy-yellow-blue until I got a crick in my neck.

Video: kiting bee-eaters, the flash of those precision-cut wings

I wondered if anyone passing by would be curious what I was looking at, standing there on the path, whether I should be marshaling my French to tell a passerby about the guêpiers. But no one broke trajectory nor gave a second glance from their bikes, rollerblades, or strolls; they left the birdwatcher to her rêverie.

There were sleek, dark swallows amongst the bee-eaters, skimming and skipping across the water’s surface, sharing a perch on a dead tree branch that stood out gray-white against the Dent de Crolles. I let my eyes rest along the line of the Chartreuse cliffs, cyclists passing along the opposite bank, the green-gold fields, the soft sky, all buoyed up by the under-bubbling of song, water, crickets. Then I refocused my binoculars on the bee-eaters.

Video: Sound on for the burbling song (more recordings and videos here)

As a lark, I tried my hand at binocular-lens photography, sweating as I tried to align the lens of my phone camera, the dark circles and blearing focus of half a binocular, and the birds sharp-beaked and chatting in the tree. Somehow I actually managed to snap a wavery glimpse of those colors to take home with me.

Still, it was difficult to decide that a given long eyeful of expert wings and jewel feathers would be the last.

So it’s a good thing I got to visit them again. A few days later, I went at lunchtime with a coworker who hadn’t seen them yet. It was midday under a strong sun, the light falling very differently on the water and the bank and the mountain. The song was the same, though, and the birds were just as active.

This time I paid more attention to what their movements meant. While flies landed on my arms (which were holding my binoculars, forcing me to learn quickly to ignore the tickles) I followed a soaring bird until it executed a complex flurry, then swooped straight to a hole in the bank. I could just make out the little head waiting for lunch—whether lunch was dragonfly, bee, or wasp, I don’t know.

On this hot day there was an even greater company of flying things in the sky: hobby planes motoring around; a whole wafting troop of paragliders over the Chartreuse cliffs, forty of them at least, as colorful as the bee-eaters; a glider towed by another plane; gulls and raptors and crows; cottonwood fluff; contrails. A couple of swallows and a pied wagtail bobbing around the banks.

Julien told me this is a new nesting site for the bee-eaters; they used to breed farther downriver, but there was a flood last October that swelled over the river path in places, leaving it encased in silt, and apparently wiping out the bee-eaters’ carefully excavated holes while they were wintering in Sub-Saharan Africa. I don’t know how they decided on the new digs, but the real estate seems to suit the colony well.

The chicks will fledge sometime in July, and within a month they will all leave together for Africa. They will follow the Mediterranean coast to the Balearic Islands, orient themselves to their migratory corridor past Gibraltar, cross the Sahara over Algeria and Mali, and “overfly the rainforest belt in a single day” before they land somewhere in southwest Africa.4

What a world they roam together on those saffron-azure wings. What a world it is with them in it.

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

The French word for wasp is guêpe, so they’re wasp-eaters to the French.

I learned that the points at the end of their tails are feathers called “streamers”

Source: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/eubeat1/cur/movement

Am I alone in remarking on how amazing the bike paths look? Is there a map of dedicated bike paths like this in Isere?

Thank you for transporting me to a place I've never visited, to see birds I've never seen. I loved how you wanted to be asked by the passersby about what you were doing and satisfied that need to share the magic by going back with your work colleague. Sometimes the beauty of nature is too much not to share with others, isn't it?