There are times when you take your life into your hands out of pure naïveté. You may not even realize it until afterward. And you might decide it was worth it—it came out all right in the end, and boy did it make you feel alive.

My labmates were debating whether to go through with the Tuesday night camping trip to the Belledonne that had been proposed over Slack. Leave together from work with whatever gear everyone had, drive an hour and a bit, hike an hour and a bit, make some food, sleep à la belle etoile by a lake, come back to work in the morning. I didn’t really know why it was planned on a Tuesday or where exactly we were going, but I wanted in; I wanted mountains without having to plan. With twenty-four hours to go, however, the forecast was threatening an overnight storm. Un orage. I didn’t participate in the debate, which was happening in French in the other office, but the hinge point seemed to be whether the probability was low enough to risk it. Some weather models (these are computational ecologists talking) were more favorable than others. We could sleep in tents instead of the open air, and maybe it would just rain a bit.

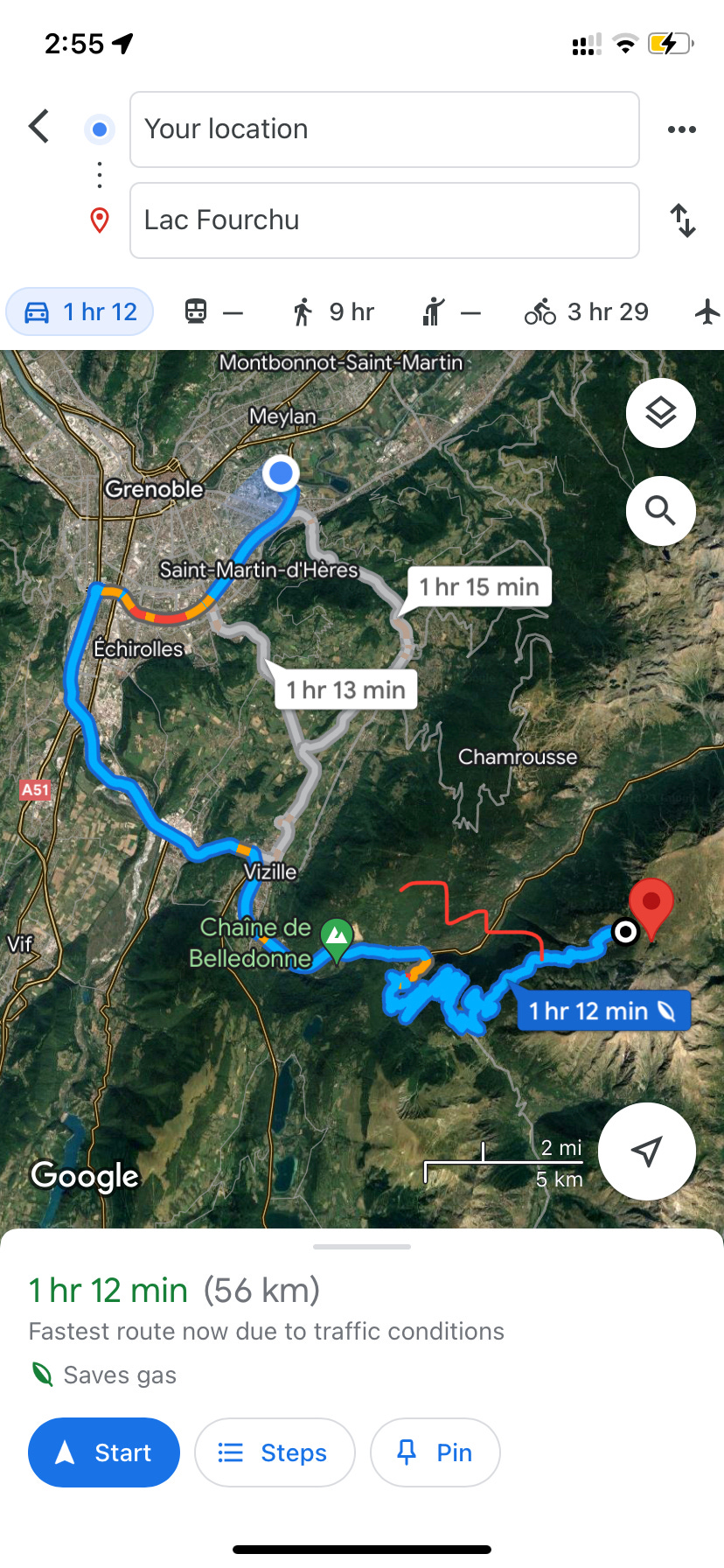

In the end, no one felt strongly enough not to go. I didn’t think about it very much, being along for the ride (one involving some extremely tight switchbacks, incidentally). We had tents, after all, didn’t we?

Grenoble, at the valley floor, is only 200 meters above sea level. The drive took us up an additional 1500 meters (hence the switchbacks), and we had 400 more to climb on foot. The worst of the day’s heat was already behind us, so we sweated up the ridge in mild evening air instead of pounding sun. When I wasn’t looking at the rocks under my feet and listening to my labmates converse in French, I looked at the trailside flowers—many still game for the alpine summer—and tried to identify them. The expanding view over wooded mountainside was hazy, but nice enough. There were pastures layered in with the trees, rooftops nestled on slopes. Someone spotted a Eurasian nutcracker, and as we neared the top of the ridge, we saw two chamois—intrepid alpine goat-antelopes—sauntering straight up the nearest rocky outcrop (see video below). My first chamois.

When the trail crested, finally peering over into the Plateau des Lacs promised by the yellow trail markers, I realized why we had come here. We were entering a new dimension, cusping over treeline onto an expanse of glacier-leveled rock slung between peaks, where glacier-melt pools in lakes and lush sedge carpets the floor, where only shrubby dwarf pines and low-lying alpine rhododendron make it above grass-height. It wasn’t truly remote, but once over the edge of the plateau, it felt like we had left the hazy human mosaic behind. The fairytale continued to unfold as we proceeded single file through the marshy land, past dusk-velvet pools shimmering placidly among the hummocks, trailing their flat, rocky streams. Then, the hollow where we would camp: a little dark lake fed by twin waterfalls cascading down a craggy cliff from the glacier above, filling the dimming air with hushhhh.

The night was quickly cooling, turning sweat-damp clothing unpleasant, but it wasn’t cold enough to be a threat. The sky was utterly clear. We sat in the grass and assembled dinner from couscous and veggies, eaten off of anything that could be construed as a plate. It was fully dark by the time we set up the collection of two-man tents; I heard the word sardines enough times that I began to think everyone was worried about how tight the fit would be in those tents, only to learn that sardine is the word for tent stake. Before turning in we sat under the stars, speculating about the various moving lights—an unusual number of satellites and planes, planting their flags even in a patch of sky where stars are spared land-based light pollution—pointing out constellations, marveling at the Milky Way, listening to the waterfalls. In the tent, I had enough cell signal to save my DuoLingo streak right at midnight.

Sleep was patchy thanks to the rising wind that flapped and nudged the side of the tent against my leg. I know I slept, though, because I dreamt. When the gale arrived at 5 am, my eyes were heavy; whether it came on gradually or with a sudden edge sweeping over the plateau, I don’t know. For a minute I had the half-awake delusion that I could keep that sleep in my eyes if I just let the rain be passing sound, like I would at home. But the pounding roar only intensified. I took off my sleep mask and saw chaos: flashing light, the tent rocking and shuddering around us. My tentmate and I pulled the bags sitting under the outer tarpaulin into the tent, just in time for me to use mine as a shield against the pelting hail I could feel through the tent wall. I imagined the whole tent uprooting and rolling us along, or tearing open for the deluge to hammer us. I began to process the fact that lightning flashing every few seconds was not good. I comforted myself with the fact that we were in a nicely concave depression with much higher rocks to attract the lightning elsewhere, only for my tentmate to calmly point out that this spot could be easily inundated. I began to picture flash flood instead. But all we could do was lie in the tent with our bags crowded around our heads, listen, wait. The roar and our bodies, and the thin shell of polyester between them, were the only things.

Within fifteen or twenty minutes, it was over. Our tent held beautifully. Someone was already walking around in the light patter, checking on everyone. Voices were incredulously cheerful, laughing in nervous relief. I looked out into the pale morning to see the aftermath, and all there was to show for it was a scattering of pebbly hail. The sedge carpet wasn’t even very wet. (I recalled now that marshes are very good at absorbing water. Flash floods are for deserts and narrow canyons.) When we told and retold the story to each other later, I would learn the word grêle, and would be repeatedly asked for a reminder of the word “hail.” I already knew l’orage (storm) and l’éclair (lightning).

The danger we had been in didn’t truly sink in, however, until the drive home. During a conversation in English, one of the experienced alpinists of the group—a lab member’s boyfriend who hadn’t been in on the planning—informed me that at that altitude, above treeline, it doesn’t matter how low-lying the ground is. Lightning will leap anywhere. And even if you aren’t struck directly, he said, you can be scorched by the conductance of a nearby strike. He had been anxiously checking the forecast every hour through the night, and had even suggested to his girlfriend that she wake us all to move downslope, but it was too late; the storm struck only five minutes later. But of course, as it turned out, we passed through the storm unscathed. (Some retrospective safety tips here.)

And after I gave up snoozing and left the tent, oh did the storm feel worth being in that morning. The sky was gentle and already warm, the sun gilded the rockfaces and glowed in the sedge, the waterfalls were white ribbons down the rock, the pond-lake glimmered with morning, and somewhere a wren was insisting on the day with its frenetic trills. I came down to the water’s edge to see tadpoles in the shallows, a fully grown frog relaxing in a boulder-top storm puddle, and an elegant pink heath spotted-orchid on the shore.

My friend and I ventured over the hill further into the Plateau and were rewarded with more rolling green strewn with roches moutonnées (glacier-ground boulders apparently resembling 18th-century wigs smoothed with mutton fat), more water flowing in ribbons from lake to lake, charming plants popping out of the sedge, small trees full of busily peeping whinchats. When I finally ambled far enough along the next lake to have a view of the plateau’s farthest horizon, I gasped with elation at the Alps fairy tale I saw there: pale blue piles of jagged peaks above the water and the green. The heart of Belledonne.

Over another hill, we looked down on the biggest lake of the plateau, Lac Fourchu—named for its forking shape—a Y of sky couched in green. Beyond the near edge of the plateau, we could see the hazy top of the “balcony” of the Vercors massif running parallel to the Belledonne, the other rib of the fork of another Y, Grenoble’s valley. We had gone off trail to see this, and, feeling like a bad ecologist, I apologized to every square inch of marsh vegetation I stepped on and tried to aim for rocks. But, like the storm, this felt like an unavoidable sacrifice under the spell of such a view.

Needless to say, we were late for work.

Truly amazing! You are living the dream. Thanks for sharing! ❤️

Magnificent!