First, a note: this post (9/18/23) marks the anniversary of my first 6 months writing on Substack about the green and human places I love and live in. I’m having a blast, and want to include as many people as want to join the journey. So, if this newsletter resonates with you, do share it! And if you haven’t subscribed, and you want a biweekly dose of green places, subscribe!

And one more thing: I’m turning on paid subscriptions. There will be no paywall on the posts and no pressure to upgrade. But if you do want to support me monetarily in this writerly endeavor, you will now have the option. Enjoy!

Winter

Garden and glacier

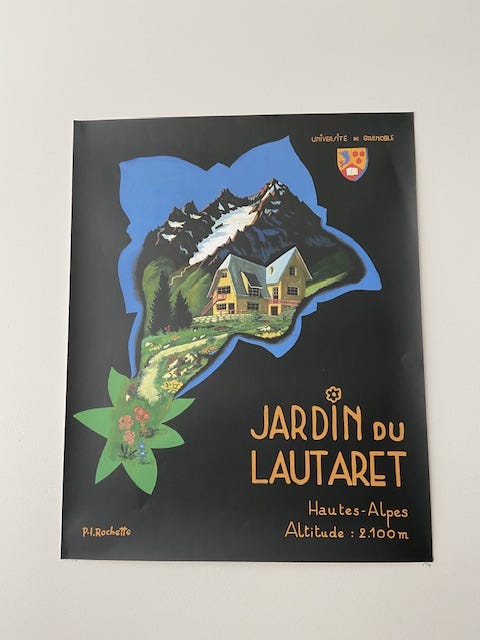

The first time I set foot in the Jardin du Lautaret, it was buried under a blanket of snow. Here and there I could see botanical plaques poking up from exposed slopes, but the carefully curated terraces of alpine plants from around the world were dormant. It was March and we were at 2100 meters.

With no plants to tempt them, my eyes were drawn inexorably across the mountain pass—the Col du Lautaret—to the peaks. Up here, there was hardly anything but peaks and their snow and sky. And yet one peak stood out, despite being set behind the others: a craggy mass of rock and snow that poured its weight into the solid mantle of white it wore. La Meije and its glacier.

I continued making my way up the snowy hill to the chalet where my labmates and I would be spending the week. The garden may have been closed for the season, but the Lautaret research station on the site was still open to researchers like us from the Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine, CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). We weren’t there to do research, but to talk about it, and also to eat quiche and go hiking together. A lab retreat. It happened to be my first week on the job, and it’s hard to imagine a more enchanting one.

The chalet is over 100 years old, stone-sided and steep-roofed. It was built when the garden, a joint project of botany professors, gentleman naturalists, and tourist bureaus, was moved to this site in 1919, and is named for Marcel Mirande, the second director of the garden. There is an excellent photo of Mirande in a pointy beard and waistcoat, looking at a microscope in a Grenoble laboratory, accompanied by large mushrooms scattered on the bench and leatherbound books and glassware in the dark wood cabinets. The garden chalet also housed an on-site laboratory at the time.

Now it is simply a place to sleep, share meals at a long table, listen to labmates sing bluegrass in French accents over aperitifs. At bedtime I opened my window to a crystalline, constellated sky and La Meije bathed in moonlight.

Every morning of the retreat we traipsed to the bottom of the snowbound garden (careful on the icy chalet steps) to the newest building of the Jardin du Lautaret, a sleek conference center cum laboratory cum museum. We gathered in a conference room and shared slides about computer models of plant communities evolving over centuries, statistical models of species competing and facilitating each other in and out of landscapes, deep-learning models for predicting changes in soil diversity from environmental DNA.

Not all the group’s research is digital-only. Sleeping under the snow on nearby mountainsides were the plots arranged along elevational gradients where, every summer, researchers roll out tape measures and clipboards and count samples of every living thing, including (later, in the lab) microbial DNA, from valley floor to nival zone. A few plots even house plugs of pasture transferred downslope by helicopter to simulate the three-degrees warmer mountainside of the future.

During breaks we stepped out onto the terrace facing the ravine and reveled in the glacier. On the slopes below, snow-kite enthusiasts were tracing the sun-crusted snow on wind-assisted skis. It was a bad snow year in Europe, worrying both skiers and those keeping an eye on reservoirs. Nevertheless, there was a midweek storm, sideways snow completely erasing La Meije for a day and biting at us mercilessly between chalet and conference center.

Before the storm, we walked easily in boots on the snowed-in road curving above the garden, a favorite of the Tour de France (requiring careful placement of alpine research plots to avoid trampling by crowds of spectators). It was also the backdrop for my first sighting of a flock of alpine choughs, which resemble crows but call to each other with trilling, plaintive cries.

After the storm, we walked in the direction of La Meije and punched into the snow up to our calves with every other step. An abandoned hut in the middle of the snowfield completed the sweep of quiet desolation.

On our last day, another storm began to clear just in time to see the marbling of cloud, rock, and snow lit up by an iridescent sun.

Summer

Glacier

The first time I set foot beside the glacier, the mountainsides were dull with dry pasture and summer smog. I didn’t reach the glacier on my own power; I rode the La Grave cable car from the floor of the Col de Lautaret over the larch forest to the glacier-side station, from 1450 m to 3200 m in 40 minutes. Within a few steps, we could see the warping, weaving, wavering plain of cracked ice spread to the far horizon of the mountain.

Now, a confession: I’ve been oversimplifying things. There’s not just one glacier, but several, slung between the peaks. A glacial basin. The one by the cable car station (la Girose) is not the one—actually two (La Meije and L’Homme)—visible from the garden, though they’re all kin to La Meije. But let’s talk about the glacier.

A glacier is sometimes called a river of ice, creaking and grinding dozens of meters per year toward the valleys. (Listen here to their dripping, crackling soundscapes.) But when you stand next to this one it seems more analogous to a lake. Not a terrestrial lake; a lunar one, if such a thing existed. A gritty, convulsing surface frozen mid-upheaval. Or maybe it’s closer to a lava flow crusted over, cracks cooling just enough to hold. Only they never solidify; they crowd slowly toward the end of the slope until the crevasses widen and break into seracs—huge chunks of ice destined to tumble.

Like glaciers everywhere, these are shrinking, exposing more and more dark-hued stone to absorb more of the growing heat. By 2100, they could be mostly gone. In the meantime, the peaks themselves are being destabilized. La Meije was the last major peak in the Alps to be climbed, but became a well-traveled summit, including those early pioneering routes. In 2018, one of those still-popular climbing routes on La Meije was obliterated by catastrophic rockfall loosened by melting ice. Things fall apart faster up here.

My friends and I didn’t have time to take a guided walk on the glacier itself, because we were going to the garden. We ate our lunch on a spine of shimmering schist and watched paragliders take off from the drop. Just three bounding steps and they were rising serenely on the thermals over the glaciers clutched by their fingers of stone, and the hazy gray slopes beyond. On our ride down, we watched mountain bikers juddering over the moonscape of bare talus slopes, the moraines of glacial off-throw. At the bottom, we ate larch-flavored ice cream (creamy and aromatic, can recommend).

Garden

Just fifteen minutes up the Lautaret road, we took the turnoff to the Jardin du Lautaret. It was my first time back since the snow of March, and though August is past the height of alpine summer, I was eager to see the garden in its waking phase. La Meije was there in the panorama, wearing its glaciers with distinction, but the otherwise bare peaks were gauzed by a veil of haze. The hillsides were dry and hissing with crickets. The garden, however, wasn’t finished.

Thistles were still in bloom, especially the silvery-purple alpine Eryngium with collars of bracts worthy of Renaissance nobility. Geraniums wove through the still-green, still-hearty undergrowth. Asters and other dandelion relatives were full-sun. I learned that the French name for larkspur is the same sense as English: pied d’alouette. The peonies were well past flowering but their fruits are framed by warm pink bracts. Edelweiss, one of the most iconic alpine flowers, were in bloom in every corner of the geographically arranged beds, including the Himalayas. The Chinese primulas were in fine form: sky blue with handsome stripes, tall and hot pink, many-petalled purple. A stream wound through peaceful groves of twisted aspens and stocky spruces and firs. And of course, there was the chalet, warm in the sun and edged with poppies and thistles going to seed.

Our favorite spot was the cushion plant beds. My friend Esther, also a plant ecologist, was eager to point out to her non-botanist husband Ed that the cushion form, that miniaturized, tight-leaved, ground-hugging alpine habit, is a prime example of convergent evolution. Many, many unrelated plant species have independently discovered that this is the best way to retain heat and save energy up in the harsh, exposed alpine zone. We saw relatives of carnations, morning glories, sunflowers, ephedra, and carrots who have evolved into their own micro-worlds of turf and spiral and blossom. We were especially pleased to find the New Zealand specimens, as Esther and Ed are Kiwis and Esther and I have both studied the poster-child of alpine diversity, the New Zealand hebes (see my homage to hebes below1). Esther bought a potted hebe in the nursery on the way out. Ed named it Phoebe.

By now, the air had cooled to the perfect balminess, and the slanting sun transformed the haze over the glacier into glory. I didn’t want to leave, but the rental car was due back in Grenoble, an hour and half and nine mountain tunnels away. Luckily for me, field work on the alpine gradients will be my ticket back: back to the high pass, the old chalet, and the garden under the spell of the glacier.

Bonus

The Jardin du Lautaret has a storied past that I couldn’t do justice to in this short post. There are not a few reasons to think it could be haunted, for one thing. But it’s also the legacy of a whole line of passionate, committed people who brought it back from the brink of disappearance multiple times. Below is a quick outline adapted from the garden’s webpage (which is in French), and maybe I’ll do a follow up history post someday.

1894: Jean-Paul Lachmann, botany professor at University of Grenoble, creates a garden in Chamrousse (now a ski station) but it’s too hard to get to and doesn’t last past 1905.

1899: Lachmann creates two other gardens in Hautes-Alpes, and the surviving one was the predecessor of the Jardin du Lautaret. The pass is also being developed for touristic travel by the railway company Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée (PLM), the Grenoble and Dauphiné tourist union, and hotelier Alexandre Bonnabel.

1907: Marcel Mirande follows Lachman as head of the garden.

1919: Construction of a new road through the site of the garden: though the university can’t afford to save it, a move to the present site is financed by the touring club of France, PLM, aristocrat and gentleman ethnographer-botanist Roland Bonaparte (grand nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte), national horticultural society and the national tourist office. A PLM hotel is already there and the chalet is built.

1930: Mirande dies and Auguste Prével takes charge of the garden.

1944: Retreating German troops attack, burning down the hotel and taking the men hostage. Prevel is killed in an explosion on the way out. Garden is abandoned.

1947-1950: Botany professor Lucie Kofler leads the effort to restore the garden, recruiting Robert Ruffier-Lanche as its head horticulturalist. (Kofler became known for studying the effect of factory pollution on lichens as indicators). Ruffier-Lanche brings in thousands of new plants and also plants trees on campus, hence the Robert Ruffier-Lanche Arboretum behind my department. His 20-year-old daughter is killed in an accident at the chalet in 1969 and Ruffier-Lanche eventually commits suicide in 1973. How sad!

1973-1981: no one replaces Ruffier-Lanche except volunteers, so the garden declines.

1981: Gérard Cadel decides to become the director and leads the effort to restore it again, raising awareness, funds, development of research and tourist infrastructure, etc

1989: second chalet built.

1990s: Tensions between managers of the garden and the university researchers, and succession dispute in 1999, until university took over entirely in 2002 (quel drama!) under Richard Bligny.

2005: Serge Aubert takes over and develops connections with CNRS and lots of prizes and designations etc; dies suddenly in 2015, succeeded by Jean-Gabriel Valay.

2016: New conference-lab-accueil building is unveiled.

Some plant science poems for Earth Day

I went into the field of plant ecology research because I love plants and the places they live in. Through scientific training, I wanted to know the natural world in a new way, complementary to what came naturally to me (observation, aesthetic appreciation, Anne Shirley-esque raptures). I also wanted to contribute to the global conservation effort, and …

Envious! And that's sea holly isn't it?

Incredible mountains, and some lovely late summer flower shots! I also enjoyed reviewing your hebe research---do any hebes grow in Utah? I have a picture somewhere I took, of what looks so much like some of your sample shots.