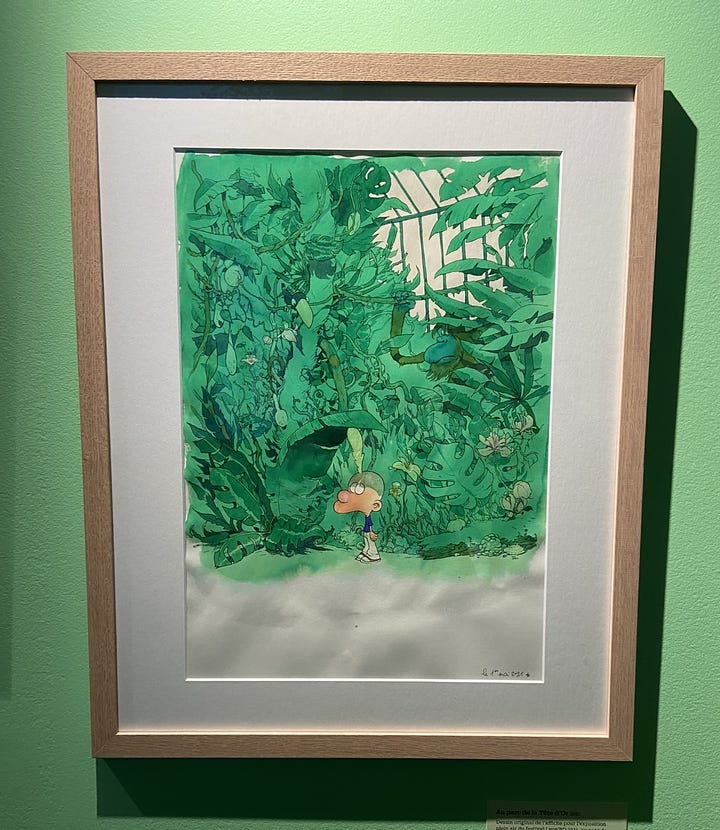

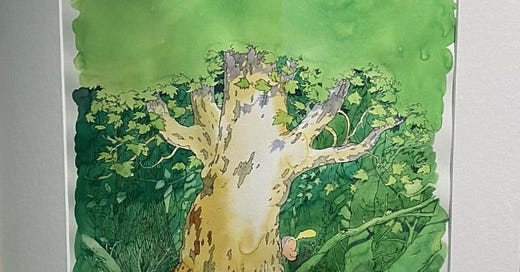

The advertising worked: a lush watercolor-and-ink tree as tall as the tram stop, little cartoon figure peering around the dappled trunk. A French person would have recognized the figure as Titeuf, probably the most well-known Francophone cartoon kid of the last few decades. But what got me was the tree, and the title: L’Arbre Dessiné (The Drawn Tree). An art exhibit possibly designed specifically for me. The location of the exhibit, Couvent Sainte-Cécile, was obscure to me, but far from being the only repurposed abbey in Grenoble. As I discovered, it may be the most niche re-invention of a 17th-century holy building around.

My friends and I showed up at Couvent Sainte-Cécile on a rain-soaked afternoon. The tall, blank outer walls of the building, all beige corners, give away little except for a banner advertising a certain Cabinet Rembrandt. But if we had paid a bit more attention, we would have also seen Titeuf again, perched in a marble niche above the big red gate.

Why Titeuf? The cowlicked kid appears to be the honorary mascot of Glénat Éditions, the publisher of Titeuf’s original bande dessinée, drawn by the artist Zep. And since 2009, the Couvent Sainte-Cécile has been the headquarters of Glénat and their arts foundation, “Fonds Glénat pour le patrimoine et la creation.” With their sleek restoration of the abbey, they’ve transformed it into a chapel to the graphic novel and the comic book.

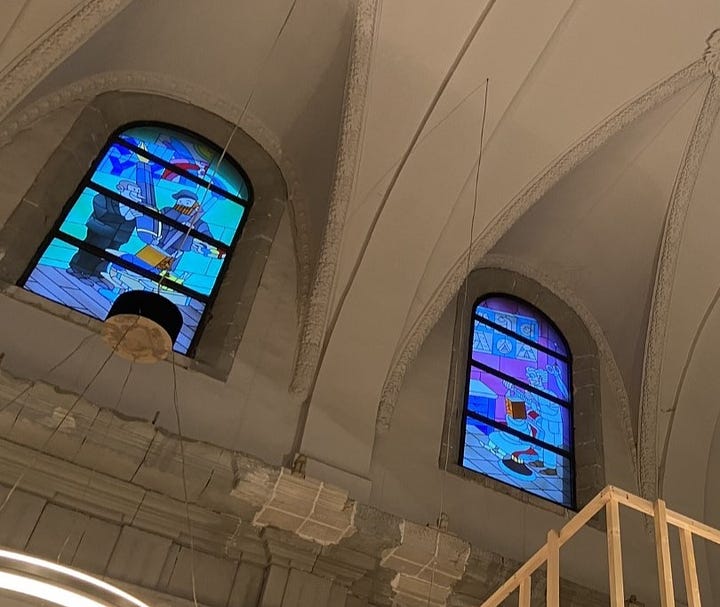

Quite literally: once you cross a small courtyard and push open the imposing walnut door, the first thing you see is a wall of books from floor to the vaulted ceiling of the old abbey chapel, scaffolded by dark metal stairways and honey-toned wood. In place of traditional stained-glass windows are charming vitraux of books living happy cartoon lives (perhaps you’ll recognize the style of Joost Swarte of New Yorker fame). Chic circular light fixtures are suspended above the central space, which, on this visit, was occupied by an array of drawings of trees.

I’ve long had a fascination with the art and narrative techniques of comics, but never really felt like I was looped into a broader community. That’s started to change here. I don’t know if it’s just a fluke of where I am and who I know—e.g., one of my coworkers is an illustrator who always brings gorgeous books from her bande dessinée collection on field trips. Or maybe it’s because I’ve gravitated to bande dessinée as a French learner. In any case, I’ve sensed here a certain reverence for and ubiquity of BD art. Not just the traditional favorites like Asterix and Tintin (which are institutions in their own right), but also artistic sci fi, slice of life, adaptations of classic novels, manga, etc. There are not one but two branches of a major BD store in Grenoble. There are multiple mononymic Franophone BD artists, like Zep, which seems to indicate (or aspire to) a certain level of notoriety. And here, on display, the success of Glénat and their illustrious lineup of artists .

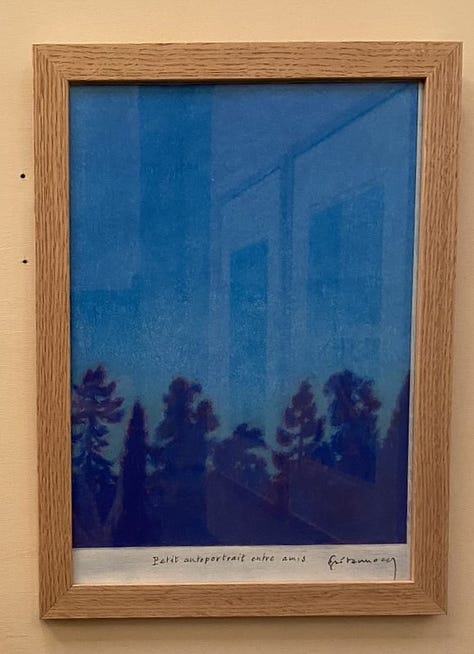

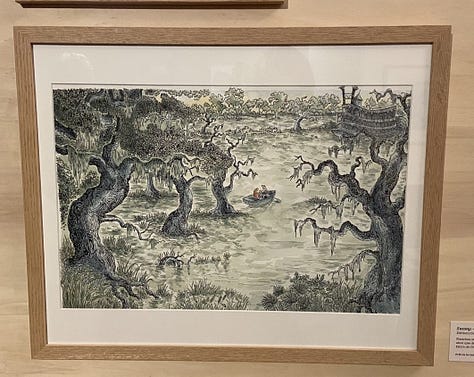

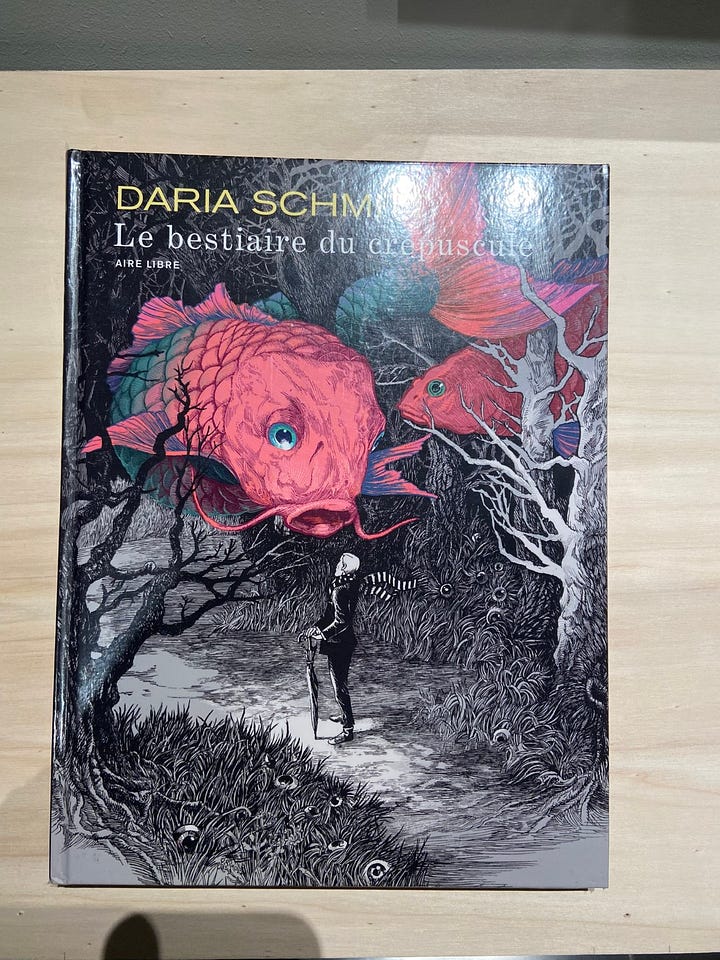

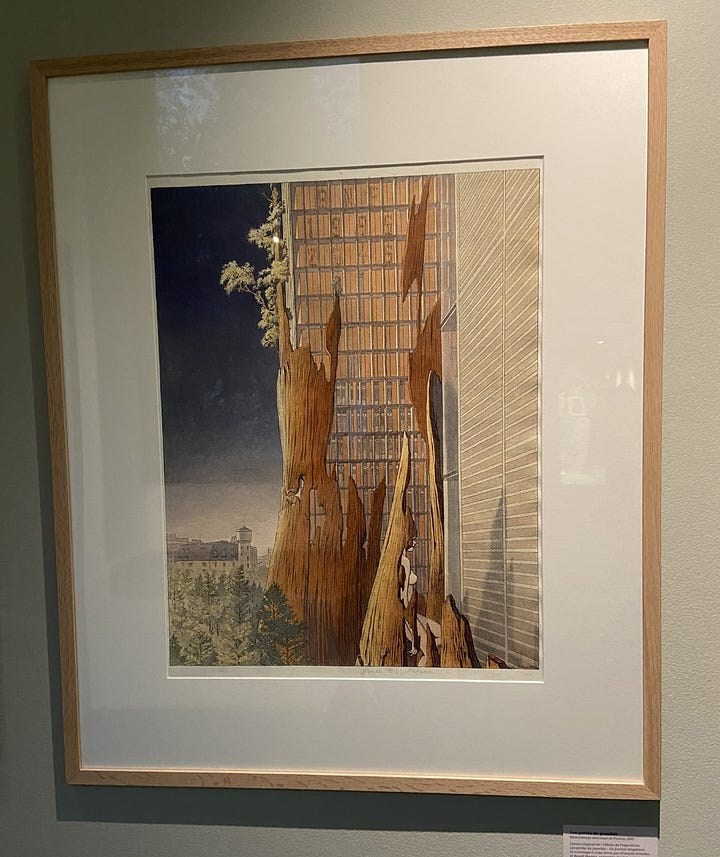

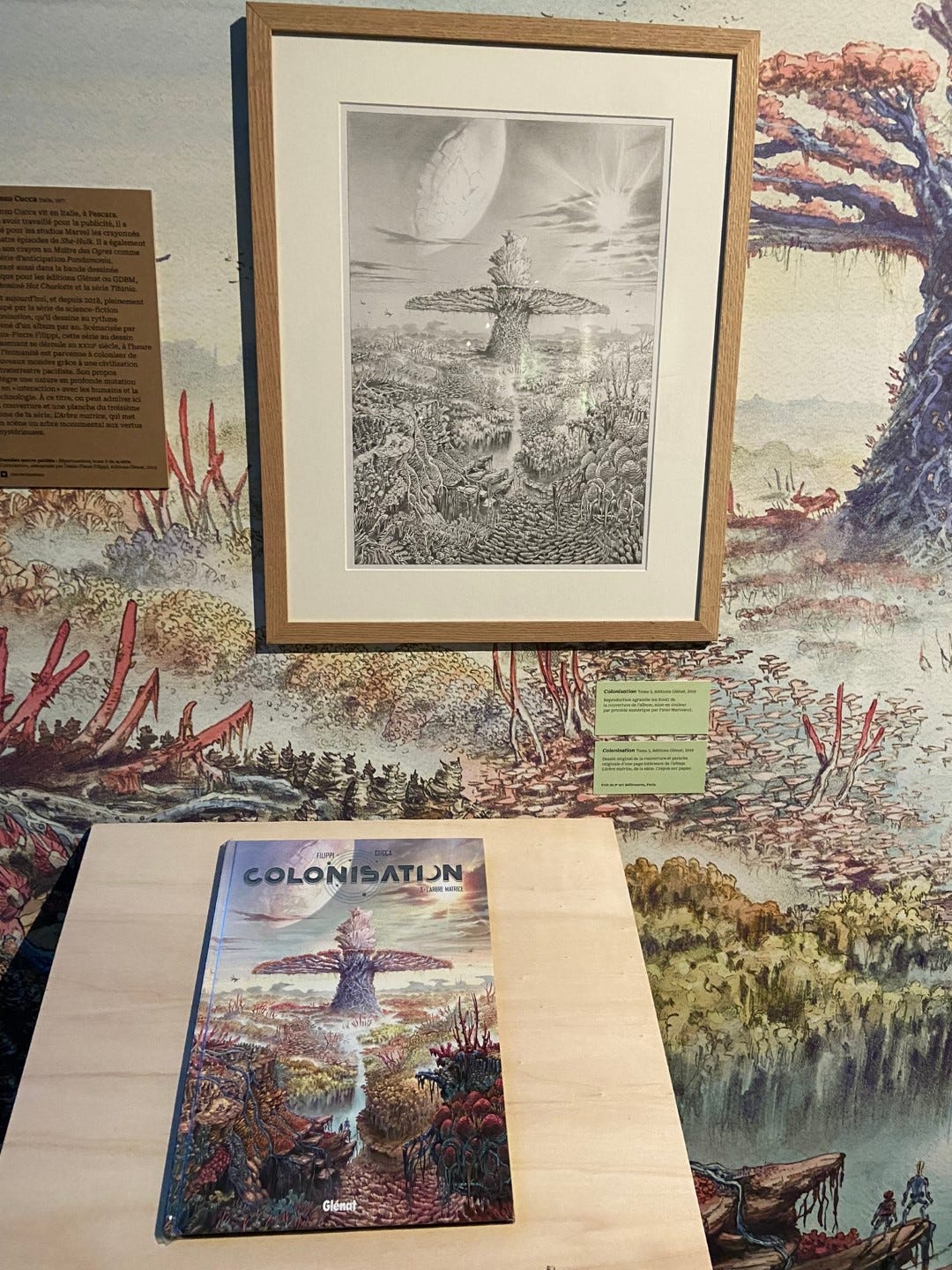

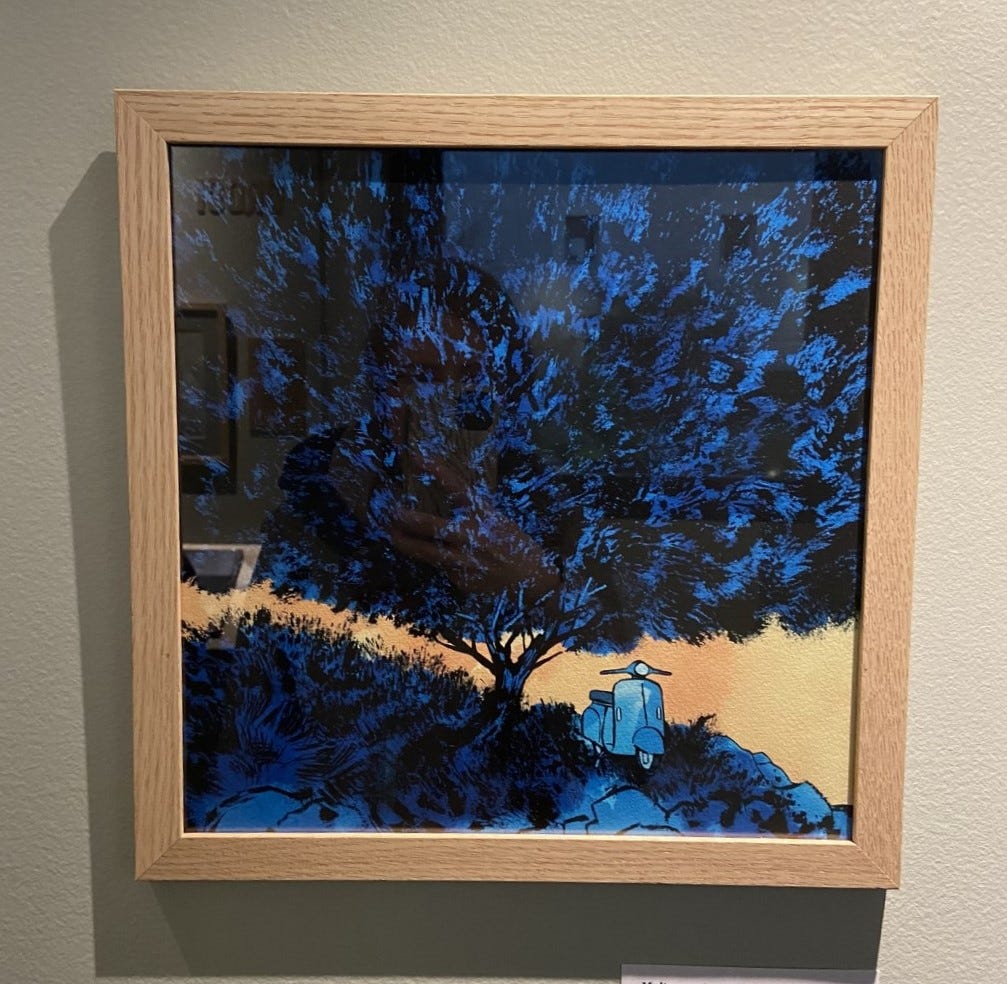

L’Arbre Dessiné took us on a wander through cloisters populated by the leafy imaginations of Glénat’s artists, styles ranging from the earthy and sensual to the post-apocalyptic to the quotidian. Each artist had provided a few original hand-rendered plates from their books, which lay on tables below the art for us to peruse. The fine and meticulous work of the planches on the walls was a testament to the labor that went into those many, many pages.

Trees were green only about half the time. It was a superbly colorful exhibit. Some trees were exquisitely tree-shaped, others more suggestive. Some were fantastical, merging with buildings, untethering from the ground, towering over an alien planet, or drifting with giant airborne koi.

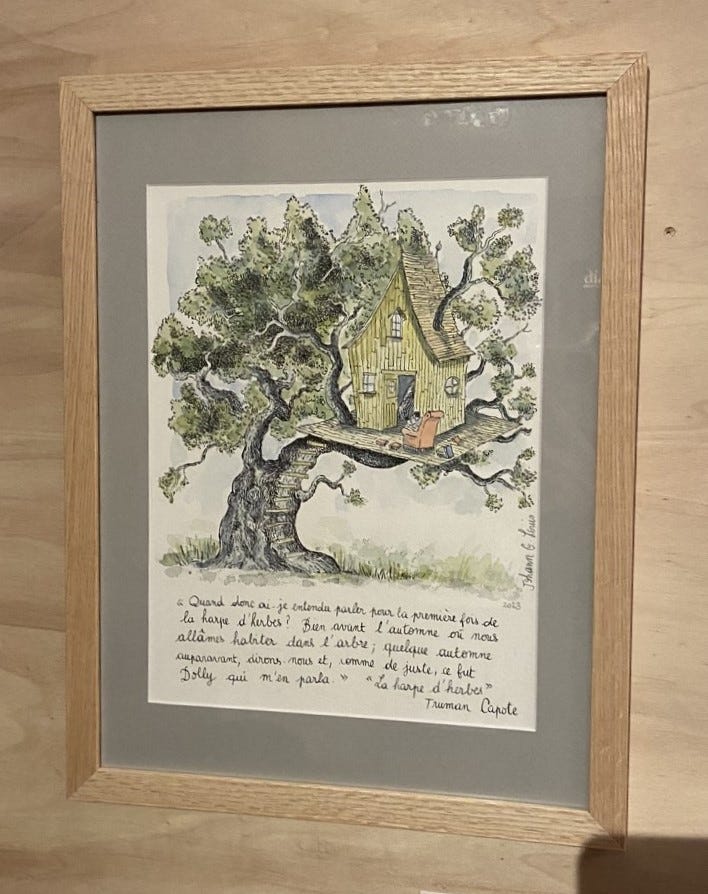

Nostalgic pastel, evocative watercolors, fine-lined ink.

The exhibit was also a testament to the place of trees in the fabric of our lives. Some books were directly concerned with trees: characters teaching their children the names of trees, or living in a tree house, or, in flight from a collapsed civilization, plunging into forest. But bandes dessinées of almost any topic could have been a source for the exhibit, given an artist who draws with some level of attention to characters’ surroundings.

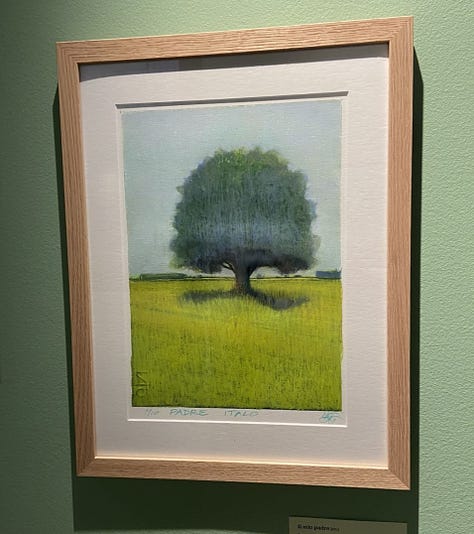

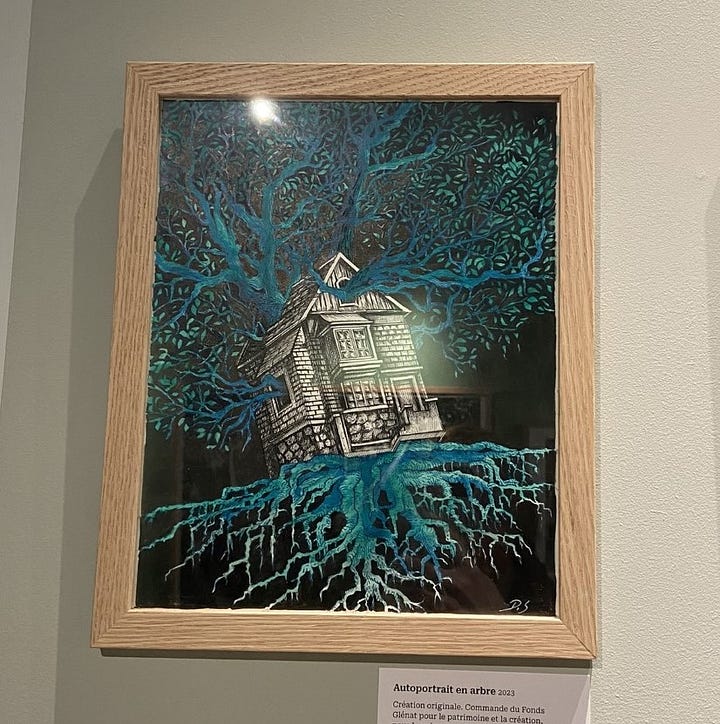

And yet, trees are more than a mere background presence. They’re in our psyches—their branching-ness, their reaching, their rooting, their stillness and their destructive force. This was proven handily by the autoportraits en arbre—self-portraits as trees, one commissioned from each artist. These were, every one, compelling psychological and creative delvings.

The untethering tree, only a single thread of root still clinging to the earth, was a self-portrait by the well-known Emmanuel Lepage. Beatrice Tillier was a dryad festooned with fungi. Johann Louis a comfortable line-drawn treehouse. Daria Schmitt an inverted treehouse, dark branches bursting from the windows. The gnarled stuff of the subconscious.

What would your autoportrait en arbre look like?

Despite the makeover given the chapel and cloisters, the abbey has retained its raw stone and centuries-worn feel. The cloister garden, which we only saw through a rain-streaked window, has been given a painstaking historical restoration faithful to the medicinal and ornamental plants of a 17th-century garden. Inside, there are wobbly doorframes and patches of unplastered stone.

What would the austere Bernardine nuns think of a wall of books in place of an altar, bursting with all kinds of colorful worldliness and wonder (not to mention a boutique selling them in the chapel)? What would they think of such radical trees lining the cloisters?

I imagine Glénat’s use of the chapel might be marginally less jarring than the abbey’s other incarnations following the Revolutionary government’s disbanding of the convent in the 1790s. It had been founded in 1624 just inside the city walls, not far from the Cathédrale de Notre Dame and a cluster of other abbeys of various orders also established in the fervor of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. After the army requisitioned the buildings, the abbey remained army barracks and offices for two hundred years. Meanwhile, the chapel itself became city property at the turn of the 20th century.

In the 1920s a film projection booth was installed in the chapel and it became a cinema. During World War II, it was briefly a synagogue, until destroyed by a Nazi militia attack on the same day as the infamous 1943 roundup of Jews in Grenoble.

After the war, it was a dance hall called, of all things, L’Enfer (Hell). And for the last few decades of the 20th century, it was a theater. The army offices only decamped from the cloisters when the abbey was sold to Glénat twenty years ago.

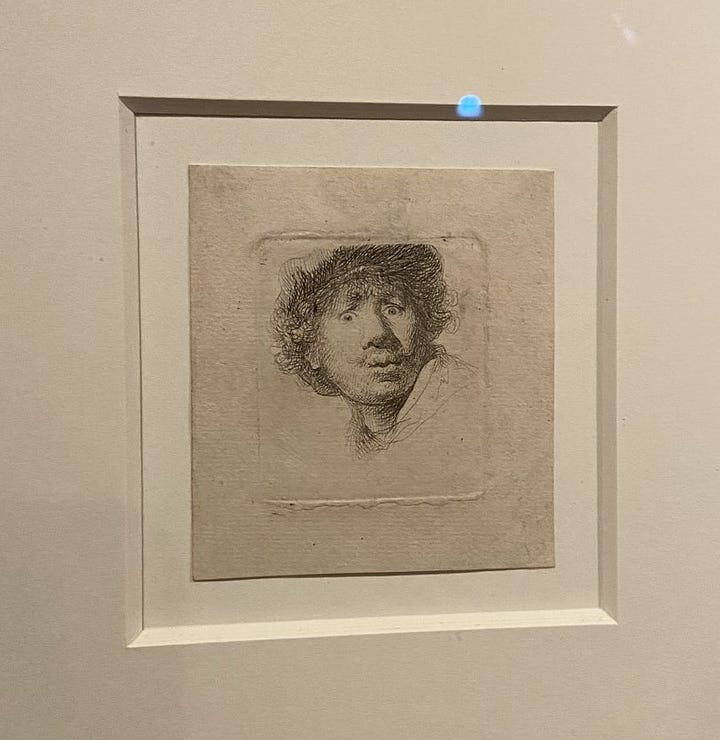

Our tickets included entrance to the Cabinet Rembrandt. This is one of Glénat’s more recent additions, a permanent collection of engravings tucked away safe from the light, with a few on display along with digital interpretive installations. (Incidentally, Rembrandt, a devout Protestant, was a contemporary of the first Bernardine nuns.)

The exhibit was small, but just as atmospheric as the trees. There was in fact an engraving called The Three Trees, which had also been digitally rendered into a meditative dynamic landscape with drifting leaves and distant flocks of birds.

It was raining heavily when we left.

P.S. I passed through the convent again this weekend, and though a new exhibit has taken the place of L’arbre Dessiné, there’s a new tree in the chapel.

This is a delight Anne from beginning to end enchantment ! Thank you for sharing though honestly, I would love to have joined you in person - an abbey full of trees an Titeuf - I mean…..! 🙏🏽

What a superb article! Both mesmerising and transporting. Your writing it getting better and better Anne, I so enjoy reading... Merci

Judy