Dear friend,

Although I have many other posts waiting, it felt like time for another one of these collections of loose notebook leaves (literally from my Notes app). (See the first one here.)

I heard an interview with the illustrious, aged Italian-French architect Renzo Piano, in which he calls nostalgia “a sort of disease (une sorte de maladie)”. While I knew the word “nostalgia” had connotations of sentimentality, I had never really heard it described so negatively. This started a thought knot in my brain, because to be honest, I love nostalgia. At least the kind of nostalgia where I wander fondly down memory lane and follow little byways into the hazy landscape of childhood. Is that bad? If not a disease, is it overindulgent? Or is it just a cozy pastime, or better yet a writer’s bountiful foraging ground? Are Renzo Piano and I talking about different nostalgias? (Possibly; more in the footnotes.1)

What is your relationship with nostalgia? I would love to know.

I’m not here to write a whole essay looking for answers (yet), but I do have some meanders in the land of nostalgia to share, which may prod in that direction.

Monuments of childhood, a microessay

Turlock, California2, a poem unapologetically drenched in nostalgia (Originally published in Segullah).

Magical thinking, a microessay

Jackie and Shadow, a recommendation (and a source of future nostalgia)

Monuments of childhood

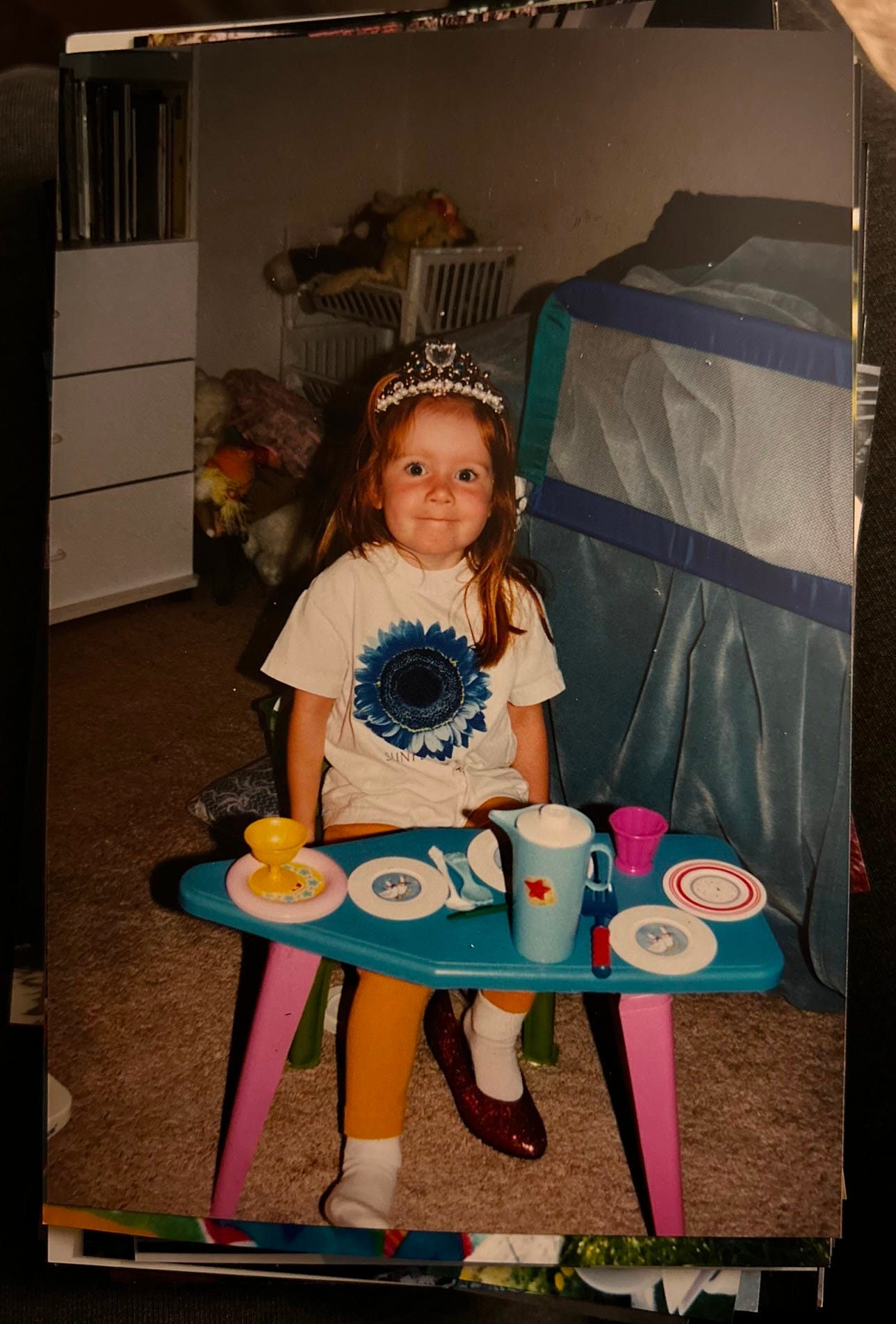

In my camera roll, I've favorited a photo of a photo of myself that Mom sent me when she was going through old duplicates, once mailed to grandparents and now reverted back to us. The photo, on top of a stack of other 4x6s whose edges are shuffled slightly into view, shows me around age 4 in my bedroom on Georgetown Avenue. I'm sitting on a child-sized chair in front of a plastic toy ironing board, which is serving as a table for plastic toy tea-time.

I appear to have dressed myself: t-shirt emblazoned with artificially blue sunflower, mustard-yellow leggings, white socks, a too-big sparkly red shoe from the dress-ups on one foot, and, pushing my bangs back from my forehead, a blingy plastic tiara. For the camera I'm smiling an obliging closed-lip smile that presses into my residual baby fat and widens my dark eyes. The resulting expression is something between jaunty and deer-in-the-headlights, tipped in the former direction by the tiara and the single sparkly shoe and the jumble of miniature plates and cups spread exuberantly in front of me. I'm clearly enjoying myself, and clearly feel in charge of my private world.3

That's one reason I've saved the photo, for that charming creative chaos and cheeky face. Another reason is of course the nostalgia of the material setting. I don't remember the ironing board, but I remember the delicate little plates with pairs of beribboned white ducks on wedgwood blue, and the matching blue pitcher with its slender spout. I remember the blue sunflower, even if only from photos. I certainly remember the sparkly red shoes, which were a staple of the dress-up box for years afterward, sequins rubbing bare. I remember the bed with the detachable mesh guard rail on the open side, and me wedging against its give, and the slippery fuzz of the spilling-out dusky-blue blanket. I remember the white particle-board dresser/bookshelf, though its drawers are shut and picture book spines lost to the gloom.

Every physical stroke, every texture and color of a child’s world is a monument. Of course a photo like this is a window onto a lost civilization.

But beyond the wistful gravity of nostalgia, I see a reminder looking out from my own eyes of what a happy childhood it was, what a beautiful gift of flourishing my parents made possible for me.

I've said before that if given the choice, I wouldn't choose to roll back time and revert to my child self, despite its happiness, because I value the widening of the world that adulthood has brought, the vast complex world that I relish as much now as I did my tiny one then. Steeping in this nostalgia makes me reconsider that trade, these days. Maybe I've lived long enough now to begin to recognize the illusion of scale, how minimal the difference truly is between my child and adult awareness of the world, how the latter is even in some ways more limited than the former as I set down grooves that are only getting deeper with time.

Or maybe it's a copout to see the impressionistic brightness of childhood as somehow more worthy or appealing than the growing-up work of individualization and agency. The inspirational quote answer, at least, would be to try to cultivate the openness of childhood even while accepting the deepening. Build monuments; keep building.

Turlock, California

While the long grain softens in the kitchen table of round-edged honey maple—fork-scarred, newsprint-stamped, marker-grazed, shin-grazing— my childhood steals along in socks and murmured songs. While the long grain ripens in the valley and the granite dome shimmers above the orchards and the Japanese maple sinks its root through the bottom of the pot and the grey-copper cat suns on the patio, my childhood drifts with the winged seeds and the almond blossoms. While the long grain pixelates in suburban shadow on the video camera, catching rubber bounces and rainbows over half-built houses and evening sprinklers and strollers on the street corner, my childhood nests in the eaves with the mourning doves waiting to come to me again.

Magical thinking

When I was roughly 11, fancying myself a poet (as I had since at least age 54), I joined a session of a poetry group my parents were hosting at our house (the one from the poem). Inspired by the sunset-petalled rosebushes my mother had planted in our backyard, I wrote a short poem in my cheap spiral-bound pocket notebook about a rose and its beauty.

The last couplet was something like

No matter what happens she will always be there.

When those words came out in the thread of the poem, I knew they weren’t really true, but I wanted them to be, somehow. The rosebush with its vivid hues against the beige stucco wall of our suburban house seemed like it should have, as a living thing, some kind of magical staying power that a wall didn't. Or at least it sounded nice in the poem. I recall doing some kind of mental gymnastics with a scenario involving a bulldozer demolishing the house, but always missing the rose.

We all sat around the kitchen table to share our writing, a group of maybe five adults and me, half-grown and yearning to prove myself one of them. I read my poem without commentary. One of the ladies said, "I like that idea, that the memory of the rose's beauty will always stay with us." And I said something like, "Yeah." A metaphorical interpretation had never even crossed my mind, but now I saw how silly my magical thinking had been, and how much better this interpretation fit, and felt very lucky I hadn't said anything, because now I could claim credit for the adult version of my poem.

This is a nice illustration of intellectual development, graduating from literal to metaphorical, maturing in conception of the world, etc; but it’s especially poignant because of the subject itself: the impermanency of nature and life. At the time, I was just crossing this brink of awareness, even while clinging to a child's baseline naïveté about change and loss.

I’ve learned since that we adult humans never really stop clinging to this state of mind (at least the average adult human). It becomes a protective measure to think magically, most of the time, about the existence of impending and inevitable loss, or about the instability of the status quo, or the fragility of natural and beloved places as we know them (though it’s hard to escpape, these days, deepening solastalgia5). Even saying, "How nice that we'll always have the memory," doesn't really mean anything until we feel the loss.

At which point we have to learn what memory really is, how it's not the rose.

Jackie and Shadow

I just want to share that if you haven’t already discovered the somewhat internet-famous pair of eagles whose nest, 195 feet up a Jeffrey pine in the San Bernadino Mountains of California, is the subject of a livestream nest cam—their babies have just hatched and it’s a perfect time to become obsessed. I started following the Friends of the Big Bear Valley Facebook page (thanks to the algorithm) two winters ago, and for two winters, Jackie and Shadow’s lovingly brooded eggs have failed to hatch. This year there are three eaglets! They are fuzzy! They are bobbleheads! They eat strips of raw fish from their parents’ ginormous beaks!

The YouTube channel and Facebook page have copiously annotated highlight videos in addition to the livestream so you will become both educated and as personally invested as you are in Ted Lasso.

If you want more, I went straight to the source (in the form of a journal entry from 2006) in last year’s Earth Day post about a core memory from a fifth grade field trip.

A field trip to the wetlands

When I found out my fifth-grade class field trip to the wetlands might be cancelled because of rain, I cried. I already had my garbage-bag poncho made and a bag packed with snacks and notebooks—is this the reason I was so invested? I had never been to these wetlands, a state park adjoining the

This could be a difference of language, culture, or subject matter—Piano was talking about his career, the buildings he thought of as his children, and maybe the aesthetics of the past. (I didn’t understand every bit of his French.) He continued,

On peut très bien regarder dans le passé sans aucune nostalgie, puisque ce qui te tient dans la vie, vivant, ce n'est pas ce que tu as déjà fait, c'est ce que tu dois encore faire.

We can very well look into the past without any nostalgia, since what keeps you alive is not what you have already done, it is what have yet to do.

In fact, Renzo isn’t rejecting the past. I think he’s referring to a kind of nostalgia that sees the unretrievable, rose-tinted past as preferable to the present. But still, I’m not sure where this ends and sweet, uncomplicated fondness begins, even in myself.

I also wonder if the French version of nostalgie is more harshly connotated than the English... The French web dictionary defines nostalgie as “Regret mélancolique (d'une chose révolue ou de ce qu'on n'a pas connu) ; désir insatisfait”, or “melancholic regret (for something past or never experienced); unsatisfied desire.”

The English web dictionary defines nostalgia as “a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition.”

Is this the same gist? Maybe it’s just my personal connotation that’s softer; I’ve been selective with one possible nuance of the word, wistful, if not yearning for return. Or am I? (See microessay #1.)

If you’re curious: I grew up in California until age 16, when we moved to Idaho. My parents still live there, but after high school I studied in Utah and the UK and am now in France. I’ll be returning to Utah next year.

I discovered later on perusing the original photo album that my little sister was lolling on the floor just outside of the frame—funny how framing tweaks the story.

The first poem I ever published was in first grade via the school Reflections contest. It went something like:

first a fuzzy caterpillar then in a cocoon then a pretty moth flying upon the bright, bright moon

Solastalgia: an ongoing sense of loss and existential distress around a familiar environment as it changes or degrades.

Re nostalgia, I think the French emphasis on regret is rather negative. I prefer the Brazilian ( or Portugese) concept of Saudade, or the German word Sehnsucht. Both involve a certain yearning for a place or a person, but neither is associated with regret. (Although Goethe wrote a poem that roughly translates, 'He who knows yearning, knows how I suffer'. Nostalgia is another translation of Sehnsucht, but again, its power is in the poetic feelings one has about a time, not a neurotic wish to return to that time.

Oh, I loved this so much, especially your micro essays. Your photo and the description of your little self made me smile and threw me back to the days when I liked to do stuff like that. What is it about little girls trying too walk in these way too big high heels?

Your reflections on yourself and the passage of time were beautiful.

Thank you so much for sharing these with us!