When I was a child, I watched an animated short film about a girl who visits Monet’s garden1. The film was contemplative and understated, and something about the clean, quiet lines and the animated sunshine on a girl in a straw hat with her old-fashioned camera, tracing the blooming footsteps of a man in a white suit, lodged deep in my memory. I fancied myself an artist at the time, but I think it was the otherworldly dimension of this peaceful, Platonic ideal of a garden, inhabited by a girl I wanted to be, that made such an impression. Monet’s garden has lived in my head like a fairy tale ever since.

Gardens can be different shades of glorious across many months, but I felt lucky that I could choose May, the threshold between spring and summer, for my first visit to Giverny. This is the village in Normandy where Monet spent the second half of his life, architecting his garden and painting his water lilies. It’s an hour’s drive from central Paris and halfway to Le Havre, the coastal town where he grew up. I booked a half-day coach tour during a sunny long-weekend stay in Paris, and by the time I boarded the coach I already wished I had chosen the full-day tour. Indeed, an hour to circulate with the herd of tourists through the explosion of flowers, the house, and around the glimmering lily pond, twenty minutes in the overwhelming gift shop inhabiting his old barn studio, and an hour to wander the length of the village to his tombstone and back was only just enough time. Enough time to get an impression. Nowhere near enough time to inhabit the impression the way Monet, or even the girl in the straw hat, did.

The garden, called Clos Normand, is laid out in rows in front of Monet’s pastel pink and bottle green-trimmed house with gravel walkways between the beds, just as Monet designed it. The overwhelming top note of the impression: roses, roses, roses. In late May they’re tumbling over the arched trellises that line the central borders, climbing along fences and hedgerows, bursting clipped parasols into full petal. Marbled pink, sunset orange, pure cream, mauve, blush, salmon, sunkiss, crimson. Supporting that heaven is the brazen underpinning of iris: full throttle indigo and bronze and royal purple and bright white and delicate lavender and powder blue. Then there are the heady accents of poppies (coquelicots): whole fields of blowsy scarlet and gold along the roads, and clustered in the garden, opulent Oriental poppies with their huge, pleated petals and black or purple centers. Filling in the gaps: purple globes of allium, bright clouds of rhododendron, purple brassicas and asters, pink campions and pansies, carefully planted red geraniums, the last few peonies and clematis, the first few lupines and foxgloves, and eager greenery of all sorts2.

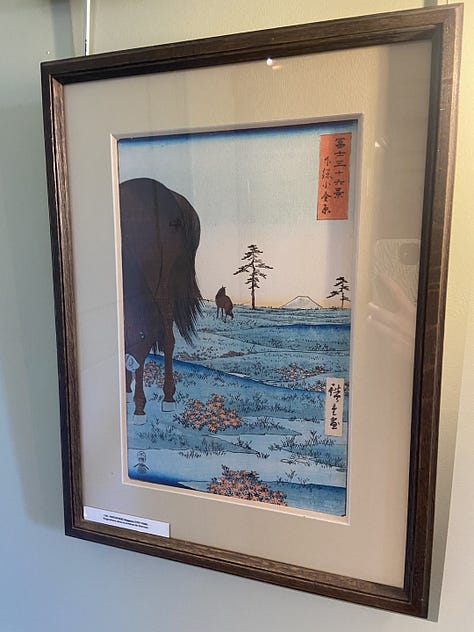

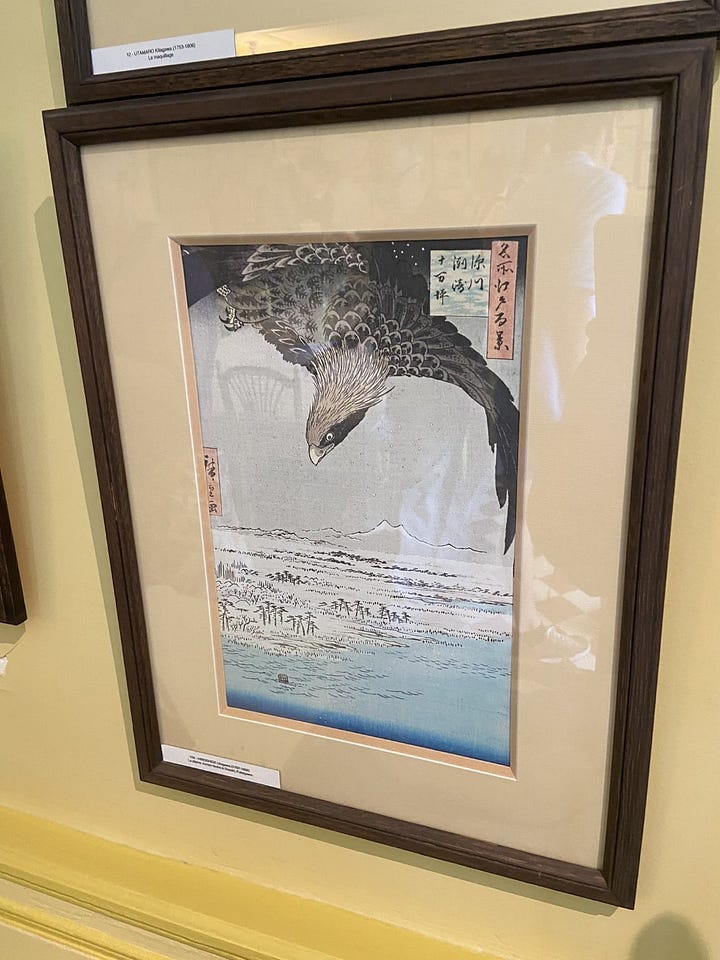

Two of the house doors, also over-climbed by roses, are open to enter and wind through the light, airy rooms. These rooms, painted yellow and blue and once full of the eight children of Monet’s blended family, strike me as a resting place for the living impressions outside. Here, the chief impression is the art crowded on the walls. Prints of Monet’s canvases have been arranged in every inch of space in the studio-sitting room, recreating an old photo of his decorating. The rest of the rooms are home to 200 18th- and 19th-century Japanese woodblock prints (half of which were in Monet’s original collection): ukiyo-e. These elegant, gentle works of art may be easy to overlook, but the more I looked, the more I was enchanted. Every curving eagle, iris, bamboo grove, wave, landscape with a single mountain, cat at window, woman nursing her baby while fixing her hair, crane, fish, and man fetching water were rendered with the same quiet detail and love for life that I sensed in the girl with the straw hat’s garden, and in Monet’s own meditations on the forms surrounding him. The Japanese water garden (still waiting for our visit) was an extension of the world he found in these prints.

To get to the water garden, Monet’s most ambitious landscaping project, you follow an underpass beneath the road. Enveloped in lush vegetation—willows, Japanese maples, bamboo groves—the pond is long and olive green, and of course daubed with patches of Nymphaea, which have only recently begun to bloom pink and white. At either end is a Japanese bridge, both of which are the same bottle green as the house trim, and one of which, of course, is the bridge almost as iconic as the Mona Lisa. I had a print of that famous painting (Water Lilies and the Japanese Bridge) taped to a chest of drawers in my childhood bedroom, and the immersive swathes of green cut through by the pastel arch of the bridge are so overfamiliar that the painting hardly makes an impression on me now. The lilies, which Monet painted unendingly for the last 20 years of his life, have so many variants that it’s easier to find novelty. I’ve been twice to the Musée de l’Orangerie, the small museum in the midst of the Tuileries Garden in Paris, where Monet’s gift of two elliptical rooms painted wall to wall with lilies was installed. There, I sat on the bench in the middle of each room and tried to lose myself in the patches of texture and color ranging from sky-delicate to pond-murky. I wanted to try the same thing here, to gaze at the water and the lily and light patches and to try to inhabit Monet’s head, to become an impressionist. Where else is there such a tangible correspondence between the world and a body of art? Alas, there were too many people and guided tours shuffling along the walkway, not to mention my niggling awareness of the time passing before I had to be back at the bus, to take a truly meditative pause. But the Japanese bridge was still hung with white wisteria, and a gardener’s row boat floated in willow shade on the other side. Even if all my photos were of strangers posing, it was not without magic.

My walk through the village was just as enchanting as the garden, with the added benefit of being off the very well-beaten track. Roses and poppies were just as abundant, gracing stuccoed or cobbled or half-timbered cottages and hotel facades3. There were swifts and house martins swooping over walled gardens, and somewhere a cuckoo calling. A meadow of poppies with paths to wander through. At the end of the main street was the small church and churchyard where Monet and many of his family members were buried. Their shared grave was overgrown with a tangle of poppies, wallflowers, foxglove, and a small rosebush, perhaps less striking than the manicured gardens, but somehow fitting. Inside the church, the stone arches were bathed by the cool blue light of a stained glass window and the warm gold of the altarpiece. There, Monet’s good friend Georges Clemenceau reportedly pulled away the black pall from Monet’s coffin, exclaiming, “No! No black for Monet! Black is not a color!” and replaced it with a flowered cloth.

I’m dying to go back—every month from March to October if I could. Maybe next time, the nasturtiums will be trailing fire over the borders and the dahlias and hollyhocks will be jostling for space.

Google unearthed it for me: Linnea in Monet’s Garden, originally a picture book. Alas, the only way to relive my childhood is to order a DVD…

A full calendar of flower seasons here: http://fondation-monet.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/calendar-of-flowering.pdf

I even found a hebe bush (the plant I studied for my PhD) in purple flower.

The names you gave the colors of some of the roses and iris are so evocative, I can see them instantly. I love the gardens, but I have to say, I couldn't help but imagine the huge amount of work they entail. Great job security for someone.

Lovely descriptive piece, Anne! You've entered a beautiful flowering world with Monet, and the description of your first childhood impression of a painting is quite captivating.