La Bastille is not only the name of the fortress in Paris known for its flashpoint role in the French Revolution (fun fact, Grenoble was the site of the very first Revolution flashpoint). In fact, bastille simply means fortress. So it’s also the name of the most iconic landmark in Grenoble: the Fort de la Bastille. Historically, being the gateway to the French Alps hasn’t only meant Grenoble a great skiing spot; it’s also had military significance. Grenoble, Capitale des Alpes, the biggest city in the French Alps, at the base of not one but three mountain ranges, would of course merit a fort. One range, Belledonne, is so vertiginous that it can’t be easily crossed. Another, Vercors, is well within the French border. The other, Chartreuse, was the weak spot, the (at times) exposed flank of Italy. And now that spot is the first place every visitor to Grenoble is recommended to check out. So, at the end of my first admin-laden day in Grenoble, I walked up from my AirBnb to La Bastille.

Almost as soon as I cross l’Isère, I’m mounting the magical stairs into the flank of Mont Rachais. The infrastructure of living and moving about on the hillside is well-built into the landscape, with old stone and concrete steps and paths leading off in many tantalizing directions and hodgepodges of walled gardens and worn buildings. I’m almost pulled in by the signs for Musée Dauphinois (an 17th century convent), leading through an archway up more stairs into the sweet, sweet unknown, but it’s already mid-afternoon and my hike is in the opposite direction. My stairs eventually lead to scrubby forest and switchbacks dedicated to la Bastille, though I’m again tempted off-course by a little woodland path that leads to a vision of concrete geometry—l’escalier des géants, a staircase leading directly up the mountainside in big blocky steps and short flights crawling perpendicularly to the flanking fortification every few meters. It looks a bit too steep to go all the way to the top, so I returned to the switchbacks where all the hikers and trail-runners and families and dogs were. I will come back down those steps later, though, and find that every step is tilted at a slightly different angle, making my already fatigued legs quiver.

The view begins to build itself from the ground up, white peaks showing faintly above the haze (but barely distinguishable from little puffs of white clouds), high rises and rooftops fanning out. The river begins to show itself, teal and curving. Layers of fortifications multiply on the hillside—stone towers and arches and gated-off tunnels, all well-decorated by the local graffiti artists. Stairs begin to cut across the switchbacks, so I take them…and they just keep going, turn after turn, layer after layer, more stone archways and landings. At one point the stairs disappear into a steep, dark tunnel angling directly through a wall. Perched on the end of one big wall is a little incongruous turret painted bright red and trimmed with other primary colors. Where archways are ungated, my child self wants very much to see where they lead, but my adult self is wary of weird people or things possibly holed away in desolate spots. But just seeing the edges and corners of so many unexplored and unexplained recesses is enough to feel myself in a setting worthy of Jorge Luis Borges (one of my favorite authors of the surreal, specializing in dark, historically obscure whimsy).

Finally, the switchbacks end at the final layer of fortress, where functional buildings perch on top of the old walls: the keep-turned-restaurant, a museum, the disembarkation platform of the Téléphérique (cable cars, nicknamed bubbles) and one more staircase to the tip-top panorama terrace. Here, I begin to hear snippets of English from tourists who took the bubbles, and French-adjacent flags from regional to international preside over the view. I am now standing at the most prominent point overlooking the fork of the l’Y grenoblois, defined here by the southern tip of Mont Rachais/the Chartreuse massif. The most impressive peaks of the Belledonne range, which is the opposite wall of the right arm of the Y and part of the true Alps, are still hiding behind the smog, made especially opaque by the harsh afternoon light. But the urban valley where I’ll be living, and the precipitous foothills that will become my daily backdrop, are all arrayed there for me. The Grenoble vieille ville below me is the red-roofed, star-rayed center tucked amid the pale, blocky concrete sprawl, hugged along its edge by the blue coil of l’Isére. The river wraps around the foot of the mountain, swinging from one arm of the Y to the other, and if I go to the other side of the terrace, I can see it making its way between the Chartreuse and the Vercors massifs (both Pre-Alps, craggy but less dominating than their big sister Belledonne). There, l’Isère is joined by le Drac, the river responsible for the stem of the Y between Belledone and Vercors. And above it all, the five plexiglass bubbles of the Téléphérique pause precipitously after each cycle of the cable.

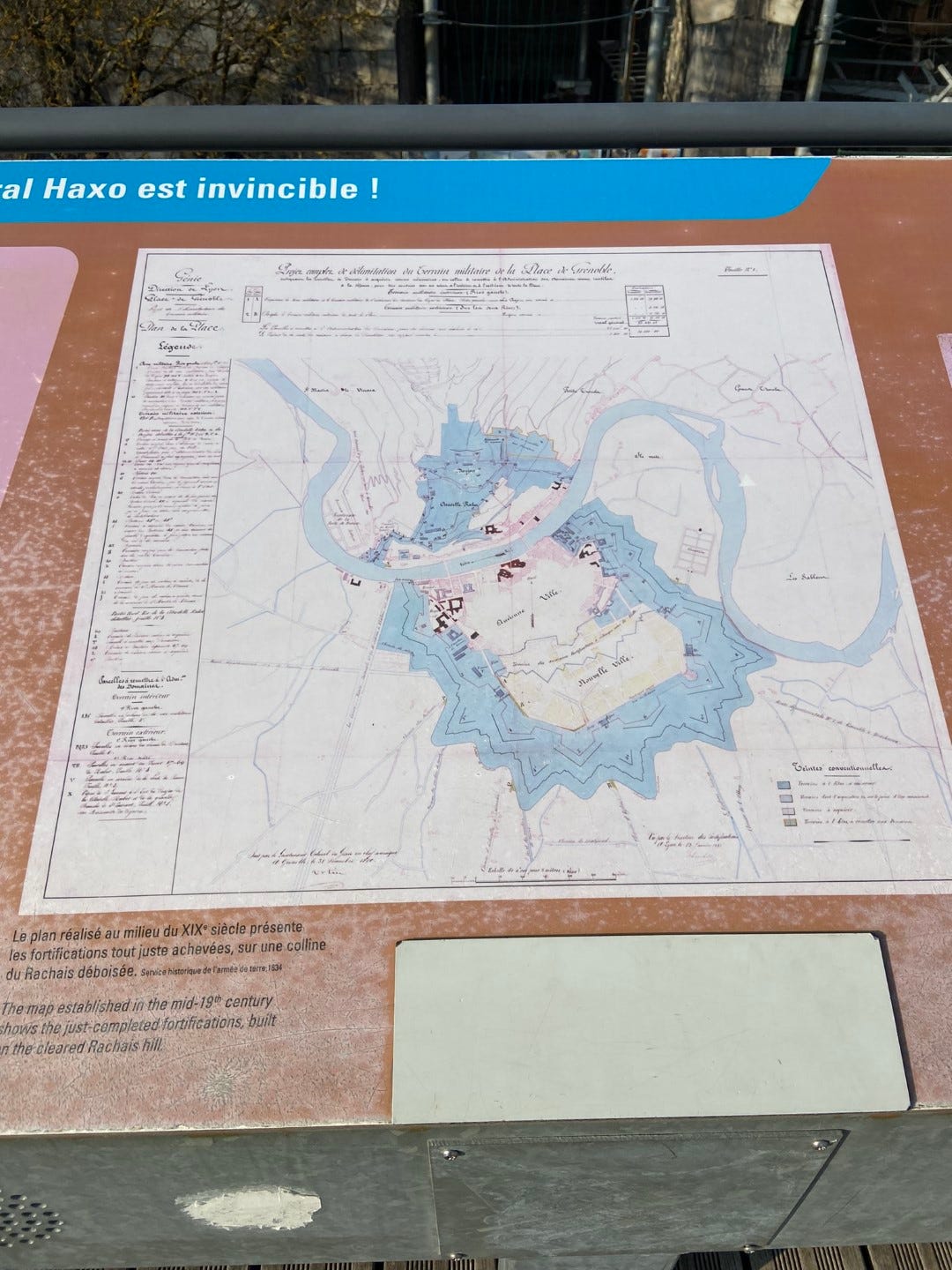

On the terrace are also informational signs, in both French and English, about the Fort de la Bastille. I learn that the strategic vulnerability of the Chartreuse has fluctuated over the centuries as lines were drawn and re-drawn. The version of the fort I’m standing on was completed by an ambitious Lieutenant-General Haxo in 1847, after shifting treaties (au revoir, Napoleon) exposed Grenoble to the alpine frontier of the Duchy of Savoy. But, as the sign tells me, not a single cannon was fired from this fort, because the Duchy was subsumed into France only 13 years later, and increasing deadliness of artillery rendered the walls obsolete anyway. Before the 19th century fort there were walls built at the turn of the 17th century by Hugenots after taking Grenoble from the Catholics, but they fell into disrepair and most vestiges were cleared by Haxo.

I wander back down the stairs and behind the fort’s defenses. For now, I bypass the museum dedicated to the troupes de montagne, the alpine troops. However, after exiting the imposing archway at the back of the fort, my wander takes me all the way along the hillside behind the fort and up a steep rocky pinnacle topped by the Monument National des Troupes de Montagne. Despite the lack of military action at the fort, it still seems to have a patriotic resonance with a regional flair that I’m curious to learn more about. Meanwhile, my walk is graced by scrubby trees that have yet to break bud, wild folds of rock, stone ruins perched on cliffs, bronzing evening light over open grass, rusted implements of defunct cable cars, someone (bizarrely) playing a trombone somewhere in the dense hillside scrub, dark caves drilled into the mountainside by Haxo which I’m too much of a rule-follower to go around the barrier and explore (for now). As I make my way back down the mountain, the haze softens into sunset tones and blue silhouettes. I link back up to Haxo’s giant stairs, jolting down all 400 of them, and leave the fort via the archway of Porte Saint-Laurent on the riverbank, one of the last remaining towers built by the Hugenots.

The smoggy view I got on that first visit was redeemed by my second visit, a jaunt via car (one threatening to break down any day, I was told) up intensely steep switchbacks of residential backstreets . It was evening and a friend had an art school exhibition in the gallery space within the stone walls—but first we went up to the terrace for the crystalline light slanting over the valley. This time, Belledonne was sparkling clean in the sky and distant peaks stood out in the remaining reach of sun. The city also caught the light, turning high-definition. I could see the long, straight Avenue de Jean Perrot (vying for the longest in Europe), and even the fountain in the city-center Place de Verdun that was at the moment dyed neon green (presumably during a protest). Vercors was deepening blue. I missed the sunset proper during the exhibit, but when we came out, Belledonne was still pink with alpenglow and l’Isère had turned satin.

Perhaps it’s a shame that so much work went into building a fortress that wasn’t necessary in the end. But although it’s not keeping anyone out, La Bastille is serving a purpose Haxo could have never foreseen: enchanting the people who live in and visit Grenoble. I’ll be back many times, I’m sure. Maybe next time I’ll ride the bubbles.

I have to admit, I needed to look up the def of 'bastille' before delving into your wonderful spiel about the local fortress, (some scarey and depressing revelations there!).

But your quick and intimate descriptions of the hike 'de jior' (I'm such an idiot), rendered your experience as a much more 'present and actual' picture if the existing place. The stairs, which somehow have continued to exist in this fragile world, seem like a throwback from Dr. Seuss, as do many of the details you thought to include.

One thing seems to stand clear though; don't give up your native English for French----youre too good at it!

What a lot of stairs! I'n glad you're being wary of weirdos. Thank you for sharing the beautiful views of your city, including the sunset shot--so nice! It's funny (and fun) that someone was playing their trombone in the hills. I love hearing about your adventures, even if it takes me a while to get to them.