When I first arrived in Grenoble, graffiti was a major texture of my first impression. Tagging seemed to show little discrimination between occupied and shuttered buildings, busy respectable street corners and dim alleys. My main encoding for graffiti was, at the time, neglect and decay. These scrawled and spiky letters and unsoothing caricatures and splashes of anger had, in my suburban American childhood, come to me from the rundown parts of town, the public spaces without enough funding or oversight to be kept "nice," or haunting liminal spaces like freight trains and abandoned industrial buildings on the side of the freeway. I admit that its ubiquity in Grenoble made me a little dismayed, even uneasy, about where I would be living.

But rising up the walls above the tagging were the fresques, the street murals. Fantastical and colorful fresques turned up every few streets, many stretching the whole height of an apartment complex or municipal building. Behind the library, a floating fox in a patched and wrinkled suit, glass-bead eyes clustered like a spider’s, a door opening onto a glowing stairway in the center of his forehead. Above the bike parking, a towering woman in sunshine yellow, rose where her mouth should be, wearing global currencies on her fingers. Across from the grocery store, a blue-haired girl sleeping curled with a lynx, sprouting leaves and flowers. On the way to church, a giant’s bookshelf behind a gash in the wall.

These pieces, clearly commissioned or at least sanctioned, lit up a different part of my brain. My love of art is well developed, and has long included public art (as well as the mildly subversive).1 When I saw these murals, I saw civic creativity, a celebration of a space that included me. They spoke openly to my art-love, eliciting the same response as a museum or gallery piece, with the added organic whimsy of being unexpected and integrated into the wilds of the built world. The goal was vibrancy and delight, and it worked. I began collecting Grenoble’s street art, Easter egg style. My civic pride grew a little with each discovery.

A side effect of my attention to colors on walls was to keep noticing the graffiti. The most noticeable pieces on my commutes and in my neighborhood started to become landmarks just like the murals. A simple sheen of silver paint left on an ivy leaf, an even more immediate sign of presence than the actual tag on the wall above it, would intrigue me. The anthropologist on my shoulder2 was beginning to wonder, What am I really looking at? Who was really here and why?

One day in June, my friend and I took an indirect hiking route to La Bastille and stumbled on the abandoned university building crouched halfway up the hillside. The building is visible from the city below but I had never given it much thought; it was derelict background noise. Up close, the outer walls were shouting with color. Inside, we saw a veritable gallery of graffiti, wall to wall, ceiling to floor, stairs and columns a chaotic collage of tagging and art pieces. On the ground, an archaeological litter of empty cans and chipped plaster. It was mesmerizing, and clearly a thing of collective pride. It was the kind of place Miles Morales would go to test his graffiti chops.

I found out later that the neighboring building had been an equal haven of graffeurs until a real estate company bought it and gave it a bougie makeover, destroying the years of art that had been left there, and meanwhile fretting about the squatt next door. It’s unclear if or when that will change.

Around the same time, I learned that the bounty of murals in Grenoble is thanks to an annual Street Art Fest, during which urban artists from the region and around the world can apply to leave their mark on Grenoble. There was a schedule posted online of the summer’s new pieces going up so you could go and watch, and there were highlight tours of the existing art. I didn’t manage to catch any of the artists in action, but I considered a tour essential to my research.

On this tour, an important reality of street art was quite literally spelled out for me: tension between the commissioned and the illicit. Among the first pieces we visited, a neon figure on a garden wall had been hastily painted over with the words, “STREET ART = VENDUES.” Sellouts.

The street artists are well aware of the limited lifespan of their work (max 10-15 years, the guide said), and that one-upmanship by illicit art and tagging is one possible end. Nevertheless, another building-sized mural we visited had been coated with a layer of anti-tagging finish to preserve it.

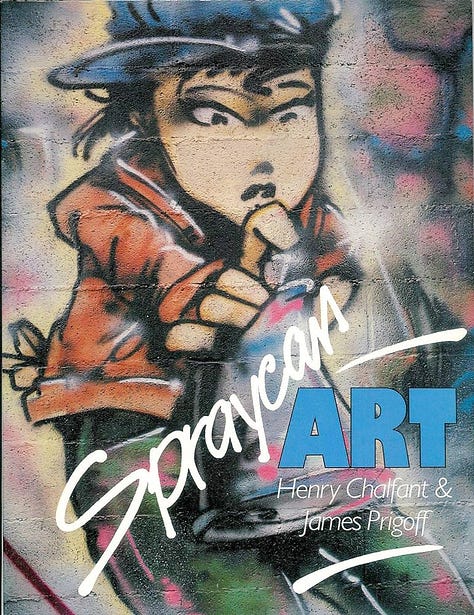

Sometimes these tensions manage to coexist. Another commissioned piece was meant to cover over an existing illicit piece by a well-known local graffiti crew. They managed to negotiate with the festival to preserve their names in the background of the new piece—which itself, an urban-aesthetic image of a girl aiming her green spray can out of the wall at the canopy of a nearby tree, seems to be a nod to famous graffiti writer Mode2, whose similar Paris character was on the cover of seminal 1987 graffiti book Spraycan Art.

Nearby, a half-submerged, cartoonishly grim face painted by a local graffeur blends perfectly into a space left by a festival mural, leaving it untouched. Others, however, were not deterred from scrawling the self-designation “vandales” in purple over the mural’s finned cars.

The lines are blurred in the artists themselves. Many, if not most, of the artists and collectives who participate in the festival, who have looked for pay and recognition from the mainstream, started out as graffiti writers and may even still do illegal graffiti in their spare time. They use the same kind of pseudonyms adopted by writers hoping to gain notoriety while remaining anonymous.

Some successful artists still remain anonymous, even while their pieces sell for millions in auction. Read: Banksy. Highly publicized French “photograffeur” JR , who does massive-scale paper photography murals on border walls and illusions outside the Louvre and celebrity portraits at the Oscars, is technically anonymous, never seen without sunglasses. (Spiderman vibes?) JR, too, was once a teenage graffiti artist who never imagined becoming an activist with a nonprofit called “Can art change the world?”

Meanwhile, this whole spectrum of motivations is clamoring from the walls, like radio waves all crowded onto one channel:

There’s basic tagging and indecipherable bubble lettering calling out to peers in the competition to claim space and glory, and to the authorities and their cat-and-mouse game of daring.

There are the crude slogans of protest and political frustration (a French subculture of its own), and destruction and defacing and subversion for its own sake: the only sense of control or voice to be found in a power structure the writers see as working against them.

Elaborate pieces meant to catch the eye of the broader public: a display of talent and ambition on their own terms, exuberant participation in a subculture that goes far beyond graffiti, encompassing hip hop, skating, and more.

Even the sanctioned art has its own huge spectrum in sensibility and purpose, from political to artistic innovation to commercial. And across all the genres, the audience—as diverse in values and interests as the city itself—decides whether they’re looking at pure vandalism, art, gentrification, commodification, celebration, or something else.

As I’ve read more about and explored graffiti and street art, I’ve waded deeper into this nuance. That initial black-and-white instinct to side with law and order, to reserve my respect for art that more or less follows the rules, has wavered. Many people have documented with admiration the rise of a neighborhood subculture in Philadelphia and New York City trainyards in the 1970s to a global movement so ubiquitous and meme-like that I grew up taking graffiti for granted as much as I do traffic lights and billboards. This is a force to be reckoned with. And the art is very often very cool.

But I’m still not sure what to make of the conflicting values of territory markers and subversive artists and community advocates and city officials and real estate agents. In Grenoble, the city sends out a small fatalistic team to clean tags that reappear within 48 hours. The founder of the Street Art Fest, Jerome Catz, tries to bridge the expressive potential of street art and the approval of the public eye, walking the line of authenticity that graffeurs prize.

Vendus or vandales?

It’s not a story with answers—just voices made visible, fading in and out.

Recently, I approached a pedestrian underpass in a nearby park and saw that it was occupied by half a dozen guys dressed in black, working on the walls with spray cans and paint rollers and detail brushes. They were staked out in broad daylight with camp chairs and a speaker pumping out hip hop. They moved loosely to the music while they worked, lit cigarettes, interjected in punchy French. Whether these walls were formally designated as open turf for urban art or not, this crew seemed at home, and anyone could stroll by without a second glance—reassuringly evidenced for me by an old lady in a sweatsuit.

So I also passed through their cave of rattle and hiss and fumes. I saw that they had blue-washed over the previous layers of tagging, and each guy was writing his own piece in his own style in a common palette of pastel green, deep purple, turquoise and silver. Most were lettering, but one guy was painting a spiky black thumb tattoo on a bearded caricature with hands mimicking pistols; another guy, grayer than the rest, was rendering a hipster-noir, shifty-eyed raven in a jacket and bowler hat. I didn't want to stare, so I came back through a few minutes later to snatch another glance at the way they finessed the aerosol into shines and shadows, and crouched and stretched and consulted over their canvas.

The next day I went to see the finished product. El Pistolero's patch had been decorated with a spray of cartoon bullet holes.

I wonder whether the crew hoped to catch eyes like mine. I wonder if they mix their talents with the mainstream, and how they feel about Grenoble’s fresques. I wonder how long before this layer is painted over.

To learn more, check out Giulia Blocal’s Substack on street art:

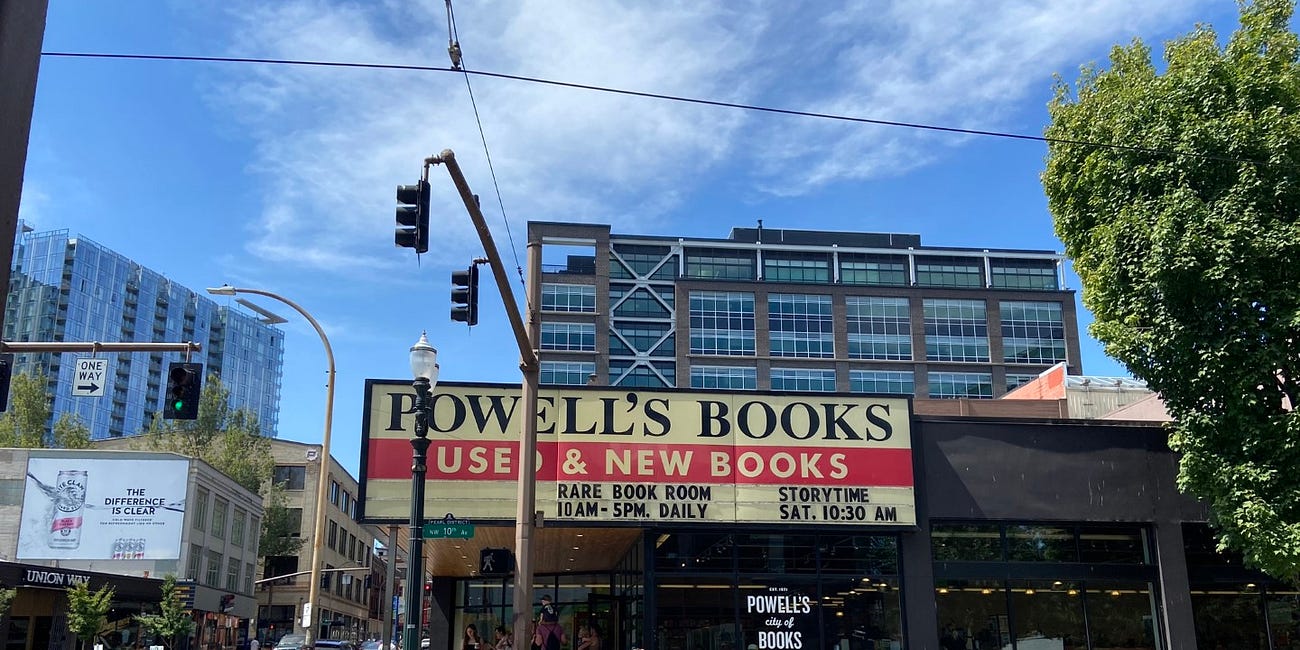

I also got a nice overview from an Art Essentials book, Street Art by Simon Armstrong. And when I went to the world’s largest bookstore, Powell’s Books, to buy that one, I didn’t manage to look at Norman Mailer’s classic book about graffiti in the rare books room. Another 1980s classic, Subway Art, was in the stacks, though. Subway Art was apparently the most stolen book from bookstores at the time.3 Spraycan Art was its sequel.

The world in a bookstore

You may or may not already know, dear Reader, that I am an inveterate bookworm. I was that kid who read fantasy books at recess and Pride and Prejudice during pep rallies (true story). I took a hiatus from this status as an oversubscribed undergrad, but once I started graduate school in a system with basically no deadlines until THE deadline, the haze c…

My favorite street art project in Cambridge is the Dinky Doors, which I wrote about on my past blog here. I also collected pictures of stealthy herons in Cambridge painted by heronheron.

Am I the only one with an anthropologist on my shoulder? Most of the time I have this meta-narrative of fascination with humans and especially pop culture going in the back of my mind.

Armstrong, p. 101

Looking forward to adding Grenoble to my street art archive 😎

I loved this, Anne! My own hometown of Boise, ID has a number of impressive street art pieces that inspire me every time I walk past them. Thanks so much for sharing these images.