Visions from the field: Three days in the Alps

In which I keep falling behind because I’m gawking at marmots, mist, and every shade of red on the mountainsides

Hello! This is an oodles-of-photos one and is very likely going to be clipped by email; if so, click on the title, or follow the “View in browser” link, or tap on “Read in App” to see the full version.

We only had one plot left to sample that last morning, but there was a mid-morning seminar someone wanted to get to back in Grenoble. Out of bed before dawn, then, and up the mountain road from the Lautaret field station before sunrise.

After the third or fourth switchback, the vision came through the van window, slurred with condensation though it was: the sea in the valley below us. For all the world I would have believed we were on a coastal road. The blue fleet of mountains crowding the gentle far horizon, which yesterday had descended in stepwise slopes to the floor of the Guisane River valley, were now submerged to their sterns in creamy mist.

The vision turned even more unearthly when I got out of the van and saw it properly. The Guisane River was visible below, as was the road following its curves, and the nearest dusky mountainsides, but so was the ethereal sea, lying discernibly against the slopes from its tranquil surface to the floor. I was seeing into another dimension. I fell behind on the short hike to the field site because I kept stopping to look back (a recurring theme).

While we worked, kneeling in the dying grass and digging little cores of soil from squares of vegetation, the sun came above the mountains. Though it warmed us up nicely, I was sure the mist would be burned away. Somehow, it wasn’t; the sea only took on a bit of the sun’s refracting glare, growing more opaque and more ghostly at the same time.

After our descent into the valley—still trying to catch that seminar—the mist was a memory, but the feeling lingered, the feeling of having stepped out of time into somewhere beyond real. It wasn’t just the perch above the mist. Every day of the field campaign had been one of visions and submersion. Everything was different up there.

Day 1

The mountain immersion came on gradually. This trip was the last of the season’s data collection from the alpine gradients, plots ranging up mountainsides to capture the communities there. The first hours of landscape felt more human than alpine; deserted ski station and hot, dry hillside pasture. We drove all the tight turns up to Alpe d’Huez, a route made famous by the Tour de France (and indeed there must be eternally a few cyclists laboring somewhere along the road).

The top plot of the gradient is also the top of a ski lift. Hillsides brown, padded poles and other piste-related infrastructure seeming rather naked; lift standing still. The plot is cordoned off by temporary electric fencing, and a laminated sign informs the passerby, “Ici, les alpages volent!”

Alpage: it’s telling that there’s a French word specifically for alpine pasture. Voler: to fly. This is the tagline for this project, Alpages Volants: sections of turf, grass, roots, soil microbiome and all, transplanted up and down the mountainside by helicopter and left to acclimate, or not, to the 3-degree change in temperature. The squares of grass brought up from below are evident here, thick and tall. It’s surprising, perhaps, given that these transplants were transferred to a colder (presumably harsher) environment rather than the warmer trade made by the high elevation turfs planted 500 meters downslope. But warm-adapted plants are moving up, and they can be vigorous in comparison to their conservative, cold-adapted new neighbors, who might struggle to keep up as the temperature increasingly favors the newcomers. On this unseasonably warm October morning, I could believe it.

Leaving two team members there to collect the soil samples that will be trawled for DNA, Tamara and I wound back down the Alpe d’Huez road to the lowest plot. Hot; grasshoppers popping out of our path, long grass, cowbells, and admittedly a nice mountain tableau. Tamara said it was her favorite site, quiet and pastoral, but I was mostly hot. The grass resisted the soil coring tool, twisting and tangling. A huge wasp spider was embalming a grasshopper.

At lunchtime we met up at the middle site of the gradient, and this was where the mountain spell began to weave in earnest. We were still in dead-grass ski territory, but there were birds. Kestrels hovering and patrolling, red kite soaring, ravens calling across the sweeping view. Binoculars out every few minutes.

We finished early and reached our home base, the Jardin du Lautaret, by mid-afternoon. I wrote about Lautaret in The garden and the glacier. Back in March, Lautaret was my first taste of the French Alps and the lab community, and in August, I had come back to see the plants still in bloom. Now, in October, the plants were finishing their winddown, but I was pleased to be a guest of the chalet again: to be in the rhythm of the place, to keep looking out the window at La Meije in the latest stage of sun-glory as evening approached and clouds morphed. Another mountain vision.

Our lab field team weren’t the only guests at the chalet. While I sat in the common room in a post-field-work laze, watching the sun move across the table, strangers came in and out and footsteps creaked across the upper floor. There were garden staff tending to the end of summer; Jerome, the head of scientific operations, being thoroughly interviewed by a journalist writing for Geo, a sort of French National Geographic;1 and later, a band of shepherds—young and beanie-wearing, both male and female—passing through to join us for dinner.

Helping Julien chop vegetables for dinner relieved me a bit from the social pressure of the long, long French evening meal. It was an hour before Julien even let me take out the aperitifs we had prepared (roasted nuts, lemony green olives, turnip slices in vinaigrette) because not everyone was back yet. Then we sat munching at the table for another hour before Julien’s stew was brought out, by then almost 9 pm.

All the evening talk was in French with occasional asides of translation for me. Despite my explicitly stated goal to practice replying in French in this immersive environment, I didn’t. I just sat and listened for context clues. I did manage to glean some topics, which I pulled out of my sleeve like a little party trick when Wilfried (my boss) asked if I was surviving the French. Anyway, even in English my introvert self would have been ready to retreat an hour before all the courses were finished. But the fromage frais with sweet, syrupy myrtilles was worth it. (Ça en valait le coup.)

Day 2

began with mist drifting swiftly across La Meije, continually revising the air. I asked Julien, who’s been coming here for years, if this was common in the mornings and he said, “It’s different every day.”

I volunteered to join the team sampling the full Lautaret gradient because I wanted to witness the whole progression from high alpine to subalpine. Five plots from 2700 meters down to 1920 meters. I was ready with my hiking poles.

The visions of the second day would be of color and creatures, geology and season. The palette would be dun and olive and burgundy, half-moon in a blue sky. We were entering the realm of burrowers, soarers, flitters, and hangers-on.

We were joined by Jerome, the Lautaret research manager. He drove the rattly garden van, in which my seat belt didn’t work2, up the curving road above the garden. The same road that would later offer the vision of mist, and the same road we had walked on, snowbound, in March.

We started with the second-highest plot, perched on a ridge with an ample view of the mountains shepherding La Guisane toward Briançon, where the sea would descend the next day. Their sides were swathed in brilliant red myrtille bushes, a coloring I had noticed the day before, now enflamed by full morning sun. La Meije peered craggily and glacially from behind. Closer at hand were rocks, rocks, rocks, clumpy grass, and a stream gurgling down through them.

This gradient is one of the network known as ORCHAMP, described in my last fieldwork post (similar to but separate from the Alpages Volants project we visited the day before, with some more of those transplant plots situated nearby). In fact, the Lautaret gradient is one of the original, flagship ORCHAMP gradients, sampled every year for changes in plant and soil life and chemistry. As with the others, our focus was the soil. This meant shoving and twisting soil corers into the rocky earth, laying on as much weight as our palms could bear, and gathering the clumps in a bag to be analyzed later for microbial DNA and chemistry. I much preferred holding the bag.

On this site we heard the first of the marmots chirping like noisy birds, and with my binoculars Jerome found them stationed on the mountainside, tan lumps blending in with the boulders. The hike up to the highest plot took us farther into the marmot domain. We followed the rocky stream and dried-mud cow trails along the gathering pitch of the hillsides, which were scattered with rocks of all sizes and stripes. Under the largest rocks it was a good bet you would find a burrow entrance; in some stretches there was a hole for every few strides. I wished I could peer past the dark and see, à la Beatrix Potter, how the marmot families lived, who was curled up inside. As it was, we got within a few meters of a marmot regarding us from a burrow at nose level; eventually we noticed the ground at our feet was spread generously with tufts of fur. Others, far enough away to be unconcerned about us, chased each other noisily, possibly angrily.

We also saw something small and lithe bounding over the rocks, and Julien said it was an ermine (like the taxidermized one sitting on his desk).

Video: Marmot surveying from burrow (wait for it…)

I wanted to stop more often, too, for the veined and eroded and striated rocks, the small flowers, the worm-like gray clumps of roots buffed by exposure, the flitting birds I couldn’t identify (though Julien listed a few French names that immediately left my brain), the flaming patches of Vaccinum (myrtille) that I would have happily looked at for the rest of my life.3

We did take a detour for the rising view of La Meije. In the photos, the glaciers that were so breathtakingly arresting to the eyes look distant behind the closer, duller ridge. You could perhaps learn to love the folds and faces of bare brown scree slopes. Far enough, and they turn blue.

Jerome tried to identify the crowd of peaks at the end of the Guisane valley, and thought we could see to Italia, but it turned out he was a bit off.

The high plot was steep and rocky, just patches of grass and alpine dwarf plants, and a deep indigo gentian peeking out from the rocks. One of the scattering of flowers that seemed not to know it wasn’t spring. We also had a view of the twisting and rippling geology of nearby peaks. Though I couldn’t read most of the stories written in that rock, this website suggests we were standing on the transition between the mythological-sounding black flysch (thinly banded sedimentary layers of schist from deep to shallow seabed) and a regional band of gypsum.

Back the way we came, pit stop at the car, and down another 200 meters of elevation to the third plot. We ended up traversing a scree slope, letting stones splay and roll almost like fluid under our feet. We stopped at the edge of a grassy hill-ridge for a bread-and-cheese charcuterie lunch, the best part of which was gazing across the valley at the red-velvet mountainside my eyes were so hungry for. Also, watching alpine choughs (the corvids I first met here in March) dip and soar in the thermals. We speculated about whether they were playing or chasing food, and decided they were playing. Jerome also identified a juvenile golden eagle, occasionally tailed by a chough.

This plot was Julien’s least favorite, presumably because of the steep approach and the fact that it was dense with Festuca grass. The tussocks reminded me of subalpine Otago, New Zealand, where I hiked once in honor of my PhD research.

On the slow climb back to the car, Julien stopped and asked for my binoculars. He had spotted a pair of enormous raptors which he identified excitedly as bearded vultures. He told me about their successful reintroduction to the Alps after local extinction, and that they’re the biggest raptors in the Alps, and that they mostly eat bones. Later, lagging behind the others after another site, I spotted them again, drifting between sky and mountain. This time I could see the diagnostics Julien had given: unmistakably huge; diamond-shaped tail. To quote my Detail Diary, the pair “made a stately magnificence of the sky as they turned together, huge and dark and tranquil.” I didn’t want to stop looking but I was being left further and further behind.

I also asked Julien about the mysterious fungus I had seen like a speckled white egg, and he immediately knew it was vesse-de-loup, which he translated as “bladder of wolf,” but just now translation I found said that bladder is “vessie” and the mushroom is definitely “vesse” which, according to French Wikipedia, is old French slang for a silent-but-deadly fart. Poetic. Anyway, I had recognized it as a puffball fungus—I poked it timidly but when it didn’t plume out spores I figured it wasn’t ready and didn’t want to thwart it.

He had also told me about the alpine willows (Salix), and I spotted a few on this walk, diminutive and hunched against rocks. He said there are ten or so species that are very hard to tell apart. Plus, succulents growing right out of a boulder, and more flowers seemingly unconcerned about the season: a creamy, downy pasqueflower, and little purple geraniums that apparently grow well in pasture because they like the nitrogen supplied by cow dung (of which there was plenty on this hike).

Fourth site: “Quite flat” walk turned out to be hilly enough to wind me. Cows not far away, lots of myrtille leafing up through the grass, a flaming red sumac in a marsh, one gnarly patch of juniper our soil plot barely missed.

Final and lowest site: Just down the road from a couple of buses full of students being taught about geology and mutually regarding a gaggle of cows. Crumbling concrete hut, autumn crocuses, view of a gorge whose rock face gleamed in the sun. Not enough energy to walk home that way as Julien sometimes does.

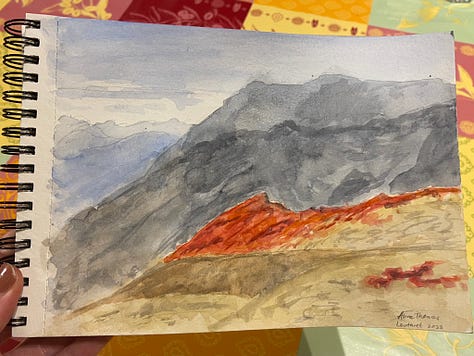

Back in the chalet, I was going to write, and instead accepted Chloe’s invitation to try her watercolors (she’s an illustrator). She was going to paint the view out the window as she had in March, but then fog rolled in and completely obscured La Meije. I painted from my photo of a brilliant red outcropping in front of the blue mountains. It was a fitting re-immersion into the landscape I had meditated on all day. With my long-neglected paintbrush, I couldn’t come anywhere near capturing the pebbly surface of the hillside in the foreground, and the shadows and ravines and ridges of the mountains were highly approximate, but the color of the myrtille was just about right. Wilfried thought it was too red until I showed him the photo.

For dinner, Julien made pasta with cèpes—but not the ones he had harvested on the last field trip because he forgot them, so he had to buy a jar at the grocery store.

Day 3,

you know about. Only a snippet of a day, but a magical one. And what I left out: A happy, cuddly greeting from a shepherd’s dog (not a patou) back at the parking, when he happened to pass by while removing fencing for the season.

Then the rush to depart, imagining some other dimension in which we could stay longer.

I wish I had tried speaking with her, being a sort of informal journalist of the place myself. I think she would have spoken English with me, but it’s funny what the assumed language barrier does to social impulses.

When offering the van’s services he had said that some “small parts” were broken but it was fine, and Tamara asked, “Which small parts? The brakes?” (She’s German.)

Not to mention my lung capacity struggling to match Jerome’s long lanky strides at the head of the pack.

I love all your work you share here, but I'm a real sucker for the fieldwork posts! Your eye is so keen, the things you notice and bring back to share with us really place the reader and observer within the environment you are sampling. The added bonus that I know these places, that mountain, that valley, this road, is just the proverbial icing on the cake.

This year, my in-laws revisited the area around La Meije, as they had climbed it (roped up and all) when they were younger. I found this rather moving, the idea of the mountain, still being there, even if the ice has retreated in that time, and the humans heading back for another look. The mountain stays within us, and stays there, physically, even as we age and, eventually, return our constituent molecules into the wider world. Moving, but also reassuring and calming. Which is an odd tangent, but one I thank you for!

Those views! Incredible. What a glorious way to spend time, and the food sounds delicious (though I too would want to retreat, combination of introversion and an increasing craving for early bedtimes -- very un-European of me).